The paper presents a model of motivation of students from Indonesia to study Russian as a Foreign Language (RFL) based on motivational factors of emotional and value nature. The RFL motivational model is structured at three levels (basic, forming and resultant) and includes the following components: a motivated subject, a motivating subject, an object of motivation, a motivational assessment, motivational modus, a motivated action, that are considered in the dynamics of their development and at the same time in application to the process of teaching Russian as a foreign language to Indonesian students.

Keywords: Indonesia, Russian language, intercultural communication, modeling, motivation, emotional and value components.

Modeling is widely used in linguistics, pedagogy, psychology, sociology, communication theory, etc., generally defined as the process and/or result of creating a scheme of an object or phenomenon [10, pp. 447]. Based on the visualization of the presented idea, the recipient has the opportunity to draw complex non-trivial conclusions, perceiving the simulated phenomenon in this way — paying attention to its key components, their interdependence, and predicted dynamics.

Modeling borrowed from mathematical and natural science fields of knowledge finds effective application in the humanities; the famous linear model of communication by G. Lasswell [12] and the model ‘meaning text’ by I. A. Melchuk [14], which formed the basis of the concept of Russian linguistic semantics, are worth mentioning, as well as an attempt to distinguish between language schemes and speech models within the framework of a dictionary description [3, pp. 796–797].

Linguistic directions with a large ‘practical’ component are all the more focused on modeling: the latter allows to clearly demonstrate the functional component that is important in the development of each specific area. Such areas, of course, include the theory and methodology of teaching foreign languages, including Russian as a foreign language (hereinafter referred to as RFL).

The phenomenon of motivation as a universal phenomenon should be recognized as one of the typical objects of modeling. Taking into account various aspects of motivation, many components are distinguished in its structure: result orientation, compulsion [2], physiological, sexual, and group needs, outburst of aggression, self-esteem [1], etc.

Career and intellectual attitudes, the causes and objectives of learning [7], the content of education, its result, duty and benefit [8] make us focus primarily on factors of educational activity that are of social nature and acquire characteristics of a certain objectivity, ‘rationality’. These aspects are considered by many authors comprehensively or autonomously.

At the same time, a detailed consideration of this topic confirms the presence of an emotional and value component in the structure of motivation, in addition to all of the above. In publications of a methodological nature, it is designated through the terms and terminological phrases: ‘emotional and aesthetic need’, ‘emotional nature of communication’ [24], ‘pleasure’ [2]. And in studies of educational motivations, it is defined through the formulations: ‘joyful sensations’, ‘subjectively experienced relationships’ [8], ‘vigorous and cheerful mood’, ‘benevolence’ [11], ‘positive attitude’, ‘satisfaction’ [17].

We accept this point of view, defining the emotional-value component as the most important factor in language learning and considering the ‘rational’ and ‘emotional’ in the structure of motivation as two independent, but closely interrelated factors.

In particular, scientists developing a theory of foreign language teaching applicable to the goals of higher education talk about the effectiveness of connecting emotions that ‘dramatize’ the situation of language communication [22, pp. 34]. The authors of manuals on the methodology of teaching foreign languages at school also point to the need to involve “emotions, feelings and sensations” of a child in this process, creating a comfortable and free atmosphere for them [5, pp. 97].

The importance of the discussed component is also noted in the formation of communicative competence, including the ability to communicate in a foreign language: “An emotional positive attitude and emotional readiness of a person for intercultural communication will contribute to their rapid acculturation, which will help an individual to be ready to interact with representatives of another linguistic culture” [15, pp. 235].

The intermediate conclusion here is that a positive emotion, an attitude towards the language being mastered as an acquired value, a positive attitude towards the subject being studied are a powerful motivational base that feeds a person’s need to learn a foreign language. It determines the acquisition of competencies that help to comprehend a new culture, expand their own abilities.

Linguistics specifies the emotional-value component within the boundaries of two categories. Here we mean:

– ‘evaluativeness’, the semantics of which is reduced to the expression of various variants of a positive / negative / neutral attitude towards an object [23];

– ‘co-involvement’, which consists in experiencing and expressing an internal mental immaterial connection felt by a subject in relation to an object [9].

Both categories, in turn, manifest themselves through the dichotomies ‘good — bad’ [4] and ‘familiar — alien’ [21, pp. 126–143; 18], respectively.

Apart from the rich scientific tradition that gives an understanding of the content and structure of these categories, which determine the significant presence of each in global and personal language practice, we will point out only one of their common characteristics — their considerable activity potential. Focusing on the fact that what is ‘familiar’ is ‘appealing’, and taking into account that what is ‘alien’ is ‘not appealing’, an individual not only forms emotional and value ideas about the surrounding reality, but plans their own activity. Moreover, it commits or does not commit specific actions. In our case, this is the activity of a student with the aim of mastering Russian as a foreign language.

The importance of an evaluation component in the structure of educational motivation is confirmed by the data of many studies, including those mentioned above. As for the phenomenon of belonging, it is studied not only by linguists engaged in studying its linguistic forms, but has its own tradition of research in psychology, where a person is defined as the main object of belonging. If someone’s concern is addressed to him/her, the relationship that has arisen is described by experts as a relationship of closeness and involvement in the personal sphere, and the corresponding feeling as a feeling of empathy for the emotional state of another person. In educational psychology, positive experience is actively used ‘instrumentally’ to increase the effectiveness of learning.

So, evaluativeness and belonging, defined as motivational factors of an emotional and value nature, reasonably become key elements of the motivation model presented below.

Taking into account, in addition, the structural composition of the communication process, as well as the given specifics — teaching a foreign language — we will: 1) reveal the component composition of the emotional-value model of motivation and 2) describe the motivational model itself focusing on the degree of its dynamism [17], that is, on the reflection of changes predicted during the development of the RFL.

The motivation model includes the following components:

– The motivated subject — hereinafter S m (‘communicator’, according to A. A. Leontiev [13]), i.e. foreign citizens studying a non-native language; in this case, Indonesians learning Russian as a foreign language;

– Motivating subject — hereinafter Ag m (‘another person’, ‘society’, according to A. A. Leontiev [13]), i.e. active participants and their groups involved in the learning process and wider socio-cultural adaptation; in this case, teachers of Russian as a foreign language, tutors of the study group, Russian students, organizers of extracurricular activities of an educational institution, etc.;

– The object of motivation — hereinafter O m (‘object’, according to A. A. Leontiev [13]), i.e. a meaningful area that is mastered in the learning process; in this case, the Russian language, the sphere of social interaction and communication, as well as Russian (possibly more broadly — multinational Russian) culture, cognized through language as a means of intercultural communication;

– Motivational assessment (hereinafter Mark m ) is a sign of axiological relationship of the motivated subject to the object/s of motivation; in this case, the assessment of the Russian language, Russian culture and social interaction by Indonesian students;

– Motivational mode (hereinafter Mod m ) is an indicator of the level of involvement that the motivated subject has in relation to the object of motivation; in this case, it is the degree of psycho–emotional involvement of Indonesian citizens in studies, language classes, communication with the Russian-speaking audience, the degree of familiarization with the values of Russian culture;

– Motivated action — hereinafter Act m (‘goal’, ‘interests’, according to A. A. Leontiev [13]), i.e. a general activity attitude, causated by motivational assessment and motivational mode, arising and developing with the participation of the two named factors.

The motivation model of teaching Indonesians Russian as a means of intercultural communication is located on three levels: basic, forming, and resultant.

Basic level — I

Forming a model of emotional and value motivation, as well as taking into account the main provisions of the ethno-oriented approach, which is becoming increasingly popular and theoretically sound [19, pp. 187], we describe the basic idea of students about the country of the studied language. Since it is the country as a geopolitical phenomenon, an object defined by its unique historical and modern content, that constitutes the initial interest of a person who has decided to expand their knowledge of the world.

Representations of this kind for Indonesians who are going to Russia or have just arrived in the country have an obvious quality of uncertainty. Of course, they can be specified by selective information from publicly available information sources. But at the same time, they are not personally mastered, because they lack the quality of ‘experience’: the latter is acquired only after emotionally felt, preferably long-term and direct contact with the object of interest.

Stereotypical knowledge is mastered for sure, since it makes up the everyday picture of the world of society, community, an ordinary person — that part which is associated with ideas about ‘countries, continents, and civilizations”. This is knowledge about Russia, which fits into a set of well-known concepts-characteristics (very distant, very cold, largest, northern country), summed up with several subject images (Moscow, Kremlin, matryoshka, kvass, birch, Siberia, North, snow, taiga, bear, etc.).

Taking into account the obvious climatic difference between Russia and Indonesia, their spatial remoteness, great differences in historical, governmental, and cultural development, and in addition, the peculiarities of religious and mental identification of peoples, the motivational mode extended by the student subject of motivation to the object can be defined as follows: 'Russia is ‘alien’, unfamiliar, an unusual and distant space, unlike ‘my’ familiar world'; in other words, it is an exotic ‘alien’.

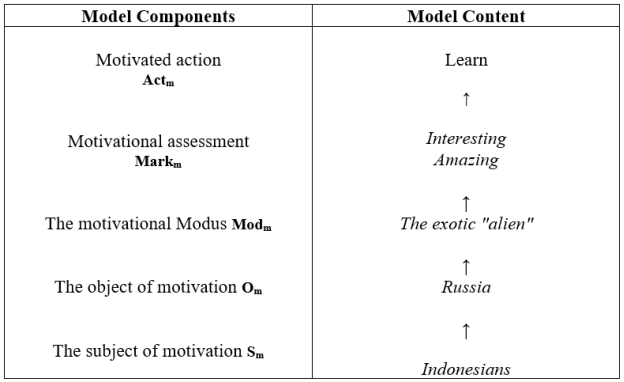

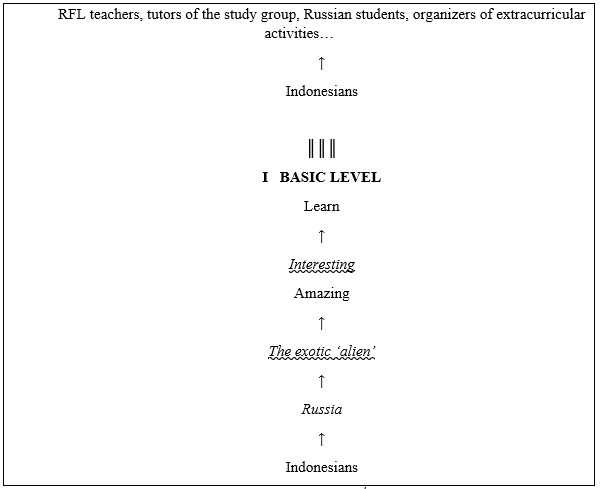

The exotic, in turn, provokes an emotion of surprise. Strictly speaking, surprise cannot yet be considered an assessment. However, it is an impression that arose from the perception of something that does not fit into the usual norm. This means that surprise provokes the subject to form an attitude towards the object that causes surprise, distinguishing it from a number of others. In the educational process, one of the main guidelines of which is to learn new things, surprise awakens and develops interest, the latter is associated with emotional assessment (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Motivational model: basic level

The level of forming — II

The second level of the motivational model corresponds to the time period of the presence of foreign citizens in the country of the language being studied. The time when motivating subjects begin to play an active role in their lives and activities: teachers of the RFL, and in addition, tutors of study groups, volunteer students involved in various events, other persons, communities, and institutions. Their goal is to contribute to the rapid and effective academic, socio-cultural and physical adaptation of students.

The idea of Russia is rapidly being specified through:

1) learning the Russian language,

2) comprehension of Russian culture, and

3) practice of intercultural communication.

Communication becomes a training space for testing and applying language competence, and in addition, it offers natural environment, typical speech situations and specific tools for exploring the history, traditions, art, and modern way of life in Russia.

At the same time, it is important not only to form a new informational and socio-cultural background to support the students’ rational orientation (career, duty, benefit, finger, etc.), but also, as mentioned above, to influence motivations of an emotional and value nature, which are often put to the test. The ‘cultural shock’ of a foreigner coming to the country of the language being studied for the first time creates the danger of demotivation.

If we describe this state of affairs by connecting the concepts of belonging, involvement, empathy, then foreign students especially acutely feel the lack of internal connection with the space and language being mastered. Then positive rational motives and incentives to study can be destroyed by experiencing emotional discomfort that occurs when encountering strangers, unusual circumstances of life and learning [6, pp. 118], the causes of which (discomfort) lie, on the one hand, in regular and necessary contacts with an atypical ‘new’. On the other hand, in the absence of the usual ‘familiar’. At the same time, the environment, culture, and language of instruction can be assigned the characteristics of partially or completely ‘alien’.

The influence of all this on the understanding of reality and on the formation of intercultural communication skills in the process of studying RFL is obvious. Therefore, the task of teaching subjects is to correct ideas about the alienness of the environment and, on the contrary, to support ideas about friendliness, cultivating a state of belonging in relation to what is happening around.

The use of an ethnically oriented approach helps to overcome the described problem in this case by taking into account the national, cultural, and psychological specifics of students from Indonesia.

The peculiarity of Indonesian society is the contamination by many cultures and religions — Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, etc. — in other words, its multi-confessional nature. Indonesians habitually perceive the world around them as diverse, not chaotic, and striving for harmony. This understanding is supported by the philosophy of the Javanese, one of the most represented ethnic groups in the country, the main provisions of which are the ideas of universal harmony and equality, the high value of friendship and mutual assistance, modesty and respect. [16].

Another psychological feature of Indonesians develops tolerance to various ‘languages and cultures’, allowing everyone to manifest themselves equally. It happened due to the history of the development of their statehood and the colonial past of the country — it is the so–called ‘elastic malleability’ — the willingness to accept someone else’s point of view without sacrificing their own [20].

The above data, as well as the results obtained during the implementation of the project and demonstrating the high interest and respect of Indonesians for Russian culture and Russian people. It creates a prerequisite for the prediction that the interest of Indonesian students in the objects of motivation — Russian language, interethnic communication, Russian culture, Russia — will be predominantly transformed into a ‘good’ rating.

The purposeful work of RFL teachers and tutors on the formation of a motivational mode will help to maintain this emotional and value background as stable.

We propose to submit linguistic, cultural and communicative material that is aimed at Indonesian students, consistently and systematically highlighting events, phenomena, subjects, categories or properties that have an Indonesian counterpart in it. If the effect of recognition arises and logical operations of comparison, similarity or identification are activated, then the relevant facts will begin to be perceived as ‘similar’, and in the future, as ‘close’ and, perhaps, even ‘familiar’. As something that a person has encountered more than once, which he/she used to trust and therefore treats positively.

In the cultural sphere, it is natural, for example, to focus on multipolarity as a vector of development of modern civilization, on environmental projects, the widespread existence of professional, traditional and informal creativity, etc. In the field of communication, it would be right to focus on the universal phenomena of politeness, etiquette, rules of speech behavior, types and styles of communication; on social networks and messengers as confirmation of globalization. Finally, in the linguistic sphere, this can be realized through the elementary identification and analysis of similar grammatical phenomena (in the system of parts of speech, morphological categories) and/or universal concepts (love, friendship, help, work, homeland, man and woman, family, children, nature, life, death, God).

It would be useful to focus the first several classes specifically on such topics in order to form a stable initial impression of similarities in the two languages and linguistic worldviews.

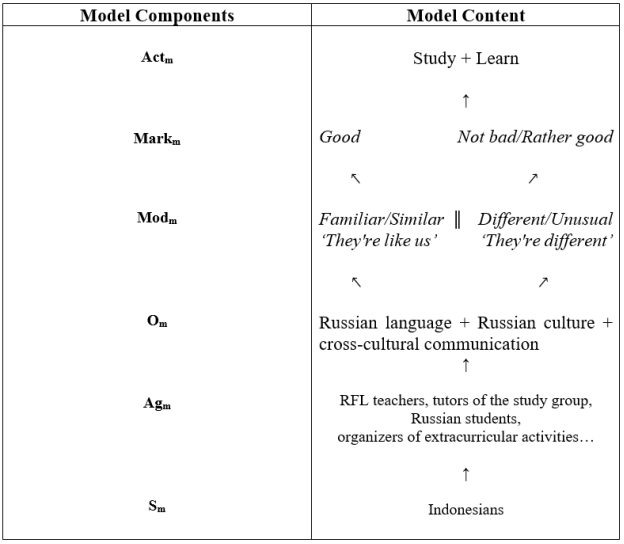

On the initiative of teachers and tutors, or on the initiative of the students themselves, differing and unusual things should also be discussed and commented on, however, with the indispensable actualization and operational consolidation of the idea of tolerance in relation to everything different in the studied linguistic phenomenon, fragment of the world or communicative situation (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Motivational model: the level of forming — II

The resultant level — III

The third level of the model corresponds to the period when systematic and intensive RFL training is completed. Teachers and organizers of extracurricular activities can still remain in the social field of the student in the roles of an adviser or expert; however, this presence is rather optional.

As a result of the purposeful and joint efforts of all participants in the process, students — with the help of a new language tool (Russian) used by them, developed speech competencies, acquired communicative experience and culture perceived through it — have not only a personal, more or less holistic and specified idea of Russia, but also a sign-oriented emotional value-related attitude towards the country.

The main substantive components of this relationship correlate with a positive assessment, which is supported by a stable attitude of belonging to the mastered Russian culture and the Russian language, which have managed to become ‘their own’ or, at least, felt as ‘familiar’.

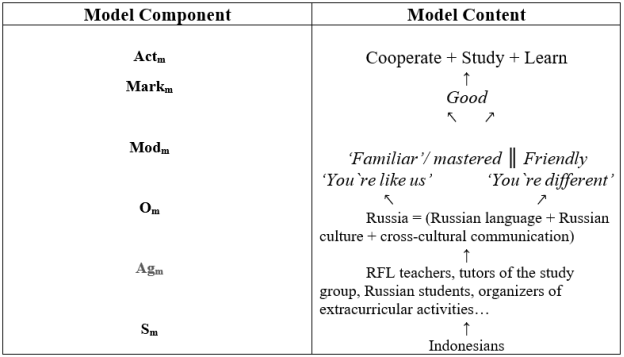

Thus, the formed motivational factors of an emotional and value nature will contribute to the development of rational — social, career, practical — attitudes and aspirations among the Indonesian audience, diverse cooperation with Russian colleagues, as well as the expansion of effective dialogue within the boundaries of a multicultural environment (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Motivational model: the resultant level

Motivating Indonesians to Study RFL Model: General Structure

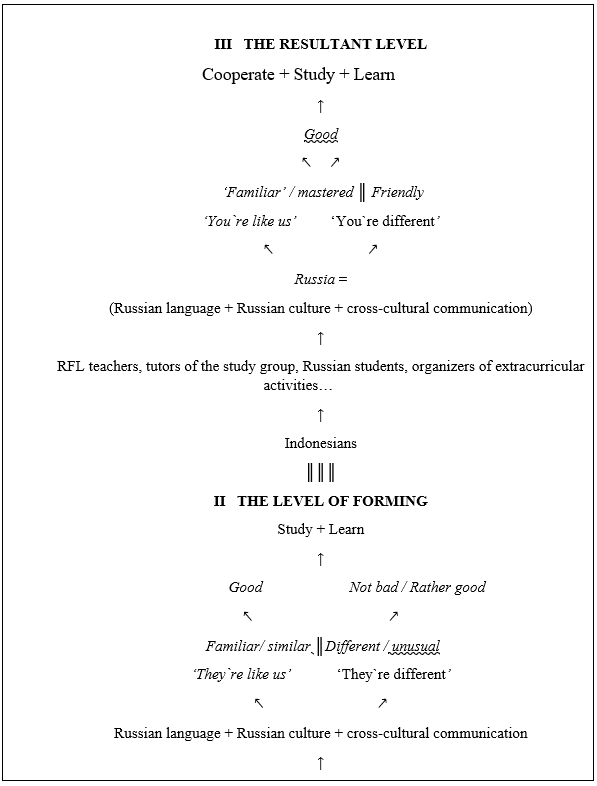

The final model of motivating Indonesians to study Russian as a means of intercultural communication, including motivating components of an emotional and value nature, is presented below (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Motivational model: General structure

In conclusion, we would like to note the following:

– the presented motivational model demonstrates: 1) the importance of the communicative-activity approach and one of its structural parts — the emotional-value component — influencing the processes of language education and social adaptation, the positive attitude of a student to these processes and the final learning outcomes, as well as 2) the theoretical and methodological potential of an ethno-oriented approach in the field of RFL, which provides the basis for creating motivational learning models aimed at the target national audience;

– the structure of the presented model — its component composition, the described interrelations and the meaningful transformation — takes into account the problems of teaching Russian as a foreign language, has signs of universality and can be used to form motivational models in relation to other target groups of foreign students.

References:

- Argyle, M. (1954). Social interaction. New York. (in English)

- Dodonov, B.I. (1984). Structure and dynamics of motives of activity. Voprosy psikhologii (Questions of Psychology). 4, 126–130. (in Russian)

- Effektivnoe rechevoe obshchenie (bazovye kompetentsii): slovar'-spravochnik [Effective speech communication (basic competencies): dictionary-reference book] (2014). Edited by A. P. Skovorodnikov. Krasnoyarsk. (in Russian)

- Filosofiya: Entsiklopedicheskiy slovar [Philosophy: An Encyclopedic Dictionary] (2004). Edited by A. A. Ivina. Moscow. URL: https://textarchive.ru/c-1108711.html (in Russian)

- Galskova, N.D. (2003). Sovremennaya metodika obucheniya inostrannym yazykam [Modern Methods of Teaching Foreign Languages]. Teacher’s Manual. Moscow. (in Russian)

- Grishaeva, L.I., & Tsurikova, L.V. (2006). Vvedenie v teoriyu mezhkulturnoy kommunikatsii [Introduction to the Theory of Intercultural Communication]. Moscow. (in Russian)

- Ilyin, E.P. (2000). Motivatsiya i motivy [Motivation and Motives]. St. Petersburg. (in Russian)

- Ilyushin, L.S. (2004). Metodologiya i metodika kross-kulturnogo issledovaniya obrazovatelnoy motivatsii sovremennykh shkolnikov [Methodology and methods of cross-cultural research of educational motivation among modern schoolchildren]. DSc (Pedagogy) Dissertation. St. Petersburg. (in Russian)

- Kim, I.E. (2009). Lichnaya sfera cheloveka: struktura i yazykovoe voploshchenie [The Personal Sphere of a Person: Structure and Linguistic Embodiment]. Monograph. Krasnoyarsk. (in Russian)

- Krysin, L.P. (1998). Tolkovyy slovar inoyazychnykh slov [Explanatory Dictionary of Foreign Words]. Moscow. (in Russian)

- Kulikova, O.V. (2008). Osobennosti motivatsii ucheniya inostrannykh studentov [Features of Learning Motivation in Foreign Students]. PhD (Psychology) Dissertation. Kursk. (in Russian)

- Lasswell, H. (1960). The structure and functions of communication in society. In: Mass Communications. Edited by W. Schramm. Urbana. (in English)

- Leontiev, A.A. (1996). Pedagogicheskoe obshchenie [Pedagogical Communication]. Moscow — Nalchik. (in Russian)

- Melchuk, I.A. (1999). Opyt teorii lingvisticheskikh modeley «Smysl <=> Tekst» [Experience of the Theory of Language Models ‘Meaning <=> Text’]. Moscow. (in Russian)

- Nurmukhambetova, S.A. (2017). Features of overcoming difficulties in learning a foreign language in the process of forming the communicative readiness of students of non-linguistic specialties. Baltiyskiy gumanitarnyy zhurnal [Baltic Humanitarian Journal]. 6(3(20)), 235–239. (in Russian)

- Ogloblin, A. K. (1988). Some aspects of traditional socialization of Javanese children. In: Ethnography of childhood: traditional forms of upbringing of children and adolescents among the peoples of South and Southeast Asia (pp. 5–38). Moscow. (in Russian)

- Ovchinnikov, M.V. (2008). Dinamika motivatsii ucheniya studentov pedagogicheskogo vuza i ee formirovanie [Dynamics of Learning Motivation in Students of a Pedagogical University and Its Formation]. PhD (Psychology) Summary. Yekaterinburg. (in Russian)

- Revenko, I.V., & Osetrova, E.V. (2022). Two “characters” in the Russian language picture of the world: “We” and “They”. Bulletin of the Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences. 15(10), 1533–1547. URL: http://journal.sfu-kras.ru/number/145415 (in English)

- Shabaiti, I., & Gao, L. (2021). Ethno-oriented learning in the system of teaching methods of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Pedagogical Sciences. 2021. No. 2 (39). pp. 441–446. (in Russian)

- Shcherbakova, E.E. (2017). Characteristics of Indonesian students in the context of teaching Russian as a foreign language. Filologicheskie nauki. Voprosy teorii i praktiki [Philological Sciences. Questions of Theory and Practice]. 2(2), 209–212. (in Russian)

- Stepanov, Yu.S. (2004). Konstanty: Slovar russkoy kultury [Constants: Dictionary of Russian Culture]. Moscow. (in Russian)

- Voitovich, N.V. (2016). Communicative activity approach in teaching RFL. In: Linguodidactics: new technologies in teaching Russian as a foreign language (pp. 33–36). Minsk. Issue. 2. (in Russian)

- Volf, E.M. (2019). Funktsionalnaya semantika otsenki [Functional Semantics of Evaluation]. Moscow. (in Russian)

- Yakobson, P.M. (1969). Psikhologicheskie problemy motivatsii povedeniya cheloveka [Psychological Problems of Motivation of Human Behavior]. Moscow. (in Russian)