In this article, the author seeks to reflect the emotional reactions of a person in relation to works of art.

Keywords: aesthetic experience, art, emotions.

Centuries before the advent of modern neuroscience, master artists sought to create works of art that would give the viewer an intense experience, evoke emotions, or even activate other feelings. Today, the neurological mechanisms underlying these responses fascinate artists, curators, and scientists alike.

The relationship between art and human psychology has long been established. Through various experiments, art has been recognized for its ability to elicit different emotional reactions in a person. Because of people’s increased levels of visual perception, the study of art’s influence, including painting, on the psycho-emotional state of a person is relevant. Many scientists, psychologists, and art historians note that art has a strong influence on the psychological state of a person, which is now serving as the basis for the formation of new trends, including art therapy.

There is growing scientific evidence that art improves brain function. It affects the brain's wave patterns and emotions, the nervous system, and can actually increase serotonin levels. Art can change a person's worldview and how they perceive the world.

The perception of an aesthetic object involves almost the entire spectrum of human mental processes, such as sensation, perception, imagination, thinking, will, and emotions. It seems that human life is unthinkable without emotions. Emotions are subjective reactions of a person to the effects of external and internal stimuli, reflecting in the form of experiences their personal significance for the subject and manifesting in the form of pleasure or displeasure [1, p. 527].

Thanks to the complex structure of the human psyche, which allows a person to interact with art and other aesthetic objects, it contributes to the limitless possibilities of forming and becoming a person, but also in the development of his creative abilities.

Emotional reactions to art (i.e., aesthetic emotions) have long been of interest to philosophers, psychologists, and art historians. Affective responses to art are very diverse and often include emotions such as awe, surprise, and even sadness and nostalgia [2, p.392]. These emotions may be related to the content and personal interpretation of the work of art, and not to its form [3, p. 175–176]. For example, one can admire the skill of Caravaggio in his work «David with the Head of Goliath», but also feel a sense of disgust at the sight of dripping blood while at the same time feeling sad at the thought that this work can express the artist's remorse.

Situational factors can also modulate the emotions associated with art. For example, the presence of other people, for example, during a visit to an art gallery, which can affect emotional responses to works of art. In addition to art education, other individual differences, such as prior mood, can also influence emotional responses to works of art [4, p. 1069].

On another level, experimental evidence suggests that providing additional information to facilitate the understanding of paintings does not affect the preference for paintings [5, p. 178]. These are the conclusions reached by psychologists from the University of Basel in a new study. Information about a work of art does not affect the aesthetic experience of museum visitors in any way. According to this study, the characteristics of the work of art itself have a much stronger influence on observers than the information about it.

Aesthetic experiences involve a complex interplay of modes of perception and cognitive processes: the properties of works of art, such as the color and content of the image, as well as the individual characteristics of the viewer, his knowledge and contextual factors, such as the title of the work, play a role.

The study involved 75 people who visited the Future Present exhibition at the Schaulager Museum in Switzerland. The exhibition presented six paintings by various artists of the Flemish Expressionist era. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups and received either simple descriptive information about the paintings or detailed information.

All those who took part in the experiment evaluated the intensity of their aesthetic experience in the questionnaire. The researchers also measured the emotional indicators that emerged when participants to the study were viewing the art, using psychophysiological data such as heart rate and skin conductivity. As a result of the study, it turned out that neither simple nor detailed information had any effect on the aesthetic experience [6, p.3].

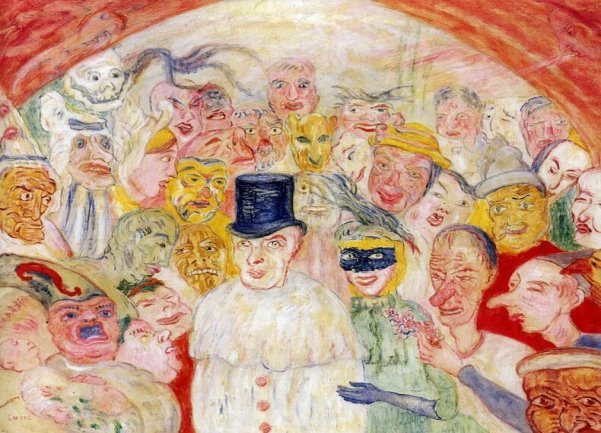

As it turned out, the aesthetic experience was influenced by the properties of works of art. At the sight of the picture, the physical reactions of the body were stronger than before the participants started viewing the painting, and differed significantly depending on a particular picture. The work of art that provoked the greatest reaction from the point of view of aesthetic experience was James Ensor's «Intrigues of Masks» (see Fig. «Les masques intrigués»).

Fig. «Les masques intrigues» (1930) by the Belgian painter James Ensor. Of the six paintings in the experiment, this painting provoked the strongest aesthetic experience. (© Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation, Photo: Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler)

Researchers believe that this kind of results could be due to a very extravagant manner of presentation of the artist, which seems a little absurd to the audience. Thus, based on the experience of Swiss psychologists, we can rightly note that a person does not need to know a detailed description of the picture in order to get an aesthetic experience. In this case, it is enough to pay attention to the canvases of artists, the art will say everything for itself by itself.

A simple look at visual art can stimulate the areas of the brain responsible for emotional processing. When we look at art, our brains are activated to anticipate and make connections, both consciously and subconsciously, making us feel happy and rewarded. Whether your reaction to the art in question is hilarious, contemplative, or somber, processing these emotions is extremely beneficial for mental health.

Whether you choose to physically engage in it or simply look at the magnificent work of others, art can go a long way to promoting mental health.

References:

1. Психология: Учебник для педагогических вузов /Под ред. Б. А. Сосновского.- М.: Юрайт — Издат, 2005.- 660 с.

2. Barrett, F. S., Grimm, K. J., Robins, R. W., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., and Janata, P. (2010). Music-evoked nostalgia: affect, memory, and personality. Emotion 10, 390–403. doi: 10.1037/a0019006

3. Robinson, J. (2004). «The emotions in art», in The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics, ed P. Kivy (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing), 174–192.

4. Hunter, P. G., Schellenberg, E. G., and Griffith, A. T. (2011). Misery loves company: mood-congruent emotional responding to music. Emotion 11, 1068–1072. doi: 10.1037/a0023749

5. Leder, H., Carbon, C. C., and Ripsas, A. L. (2006). Entitling art: influence of title information on understanding and appreciation of paintings. Acta Psychol. 176–198. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2005.08.005

6. Krauss, L., Ott, C., Opwis, K., Meyer, A., & Gaab, J. Impact of contextualizing information on aesthetic experience and psychophysiological responses to art in a museum: A naturalistic randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. 2019. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000280