Although the problem of translation of God’s names into Turkic languages was discussed by several authors, no thorough analysis was performed as to study different approaches to render the theonym YHWH into the Tatar language. This articles discusses non-translation, semantic translation, and transcription/transliteration as main methods of rendering the Tetragrammaton.

Keywords: Tatar, Tatar language, Siberian Tatar language, Golden Horde, Khazars, Karaims, Karaim language, Turkic languages, Armeno-Kipchal, Kryashen, Cuman, Kipchak, Codex Cumanicus, targums, Bible, theonym, Tetrogrammaton, translation, Bible translation, YHWH, Yahweh, Jehovah

The history of Bible translations into Turkic languages has been discussed in several sources. [1–7] In this article, we will focus mainly on those languages that were called “Tatar” either by native speakers or by neighboring nations. This group includes a number of representatives of the Turkic language family. For example, the Crimean Karaite dialect is sometimes called Leshon Tatar (טטר לשון), “the language of Tatars”. The Cuman language described by Catholic missionaries in the Codex Cumanicus (1303) is called tatar til, “Tatar language”. A dead Turkic language, Armeno-Kipchak, was also called Tatar (թաթարչա, tatarča). The Chagatay language was also called “Tatar”. [4, 10] Some 19th century researchers expanded this term to other nations and their tongues. For instance, one source lists languages of “Tatar tribes” including “Nogai-Tatar, Mongolian, Calmuck, Orenburg Tatar, Tschuwaschian, Tscheremissian, Tatar-Hebrew (spoken in the interior of Asia), Mordwaschian or Mordvinian, Ostiakian, Wogulian, Samoiedian, Tschapoginian, Zirian, Ossatinian, and a dialect of the Tatar spoken in Siberia”. [5] Besides, the term “Tatar” referred to Turkmens, Kyrgyz, Turks, Crimean Tatars, Kumyks, Karachays and Balkars, Azeri, and so on. [6] The modern Tatar language, a northwestern (Kipchak) ку of the Turkic subfamily of Altaic languages, is spoken in the republic of Tatarstan in west-central Russia and in Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey, and China.[1]

The aim of the article is not to discuss the genealogical relations between the above languages but rather to analyze approaches to rendering Biblical theonyms, including the Tetragrammaton, applied by translators of the Holy Scriptures into these tongues.

The problem of translation of God’s names into Turkic languages was discussed by several authors [12–14]. In this article we will categorize all approaches to rendering the sacred Tetragrammaton, YHWH, a four-letter name of God, found in the Hebrew text of the Bible, which is usually pronounced as Yahweh or Jehovah in English. These approaches include non-translation, semantic translation, transliteration and transcription. [15]

A brief review of the history of the Bible translation into the Tatar language

It is difficult to establish the date of first translation of a biblical text into a Turkic language. One of the earliest biblical paraphrases can be found in a 10th century Turkic book Їrq bitig (“The Book of Omens”). It is believed that one of its “revelations” reflects the Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11–32):

oo oo ooo 58. oglı ögintä k(a)ŋınta öbk(ä)läp(ä)n t(ä)z(i)p(ä)n b(a)rmiş. y(a)na s(a)kınmiş, k(ä)lm(i)ş. ögüm ötin (a)l(a)yın, k(a)ŋ(ı)m s(a)bın tıŋl(a)yın’ tip k(ä)lmiş tir. (a)nça biliŋl(ä)r: (ä)dgü ol. (A son, being angry with his mother (and) father, ran away (from home). (Later) he thought it over (and) came back. He came back saying 'l will accept my mother's advice (and) listen to my father's words', it says. Know thus: (The omen) is good.) [8]

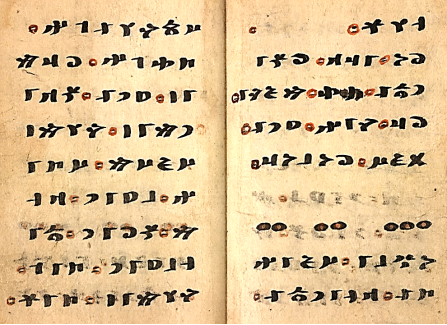

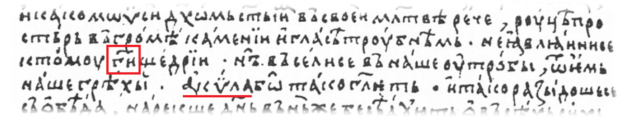

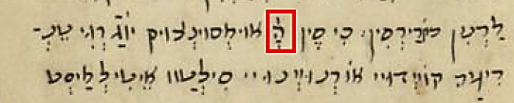

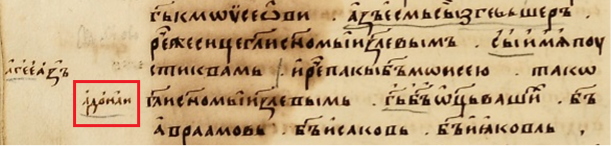

Figure 1. The beginning of Omen 58. [8]

Another Turkic translation of a biblical story (“Adoration of the Magi”) based on Luke, chapter 2, dates back to the 13th century. [9]

Codex Cumanicus is another document containing portions of the Bible translated into the Cuman language [3]. It was compiled by Catholic missionaries and its main purpose was to teach missionaries the Kipchak language and convert the population of the Golden Horde to Christianity. It contains portions from the Holy Scriptures, sermons, songs, and Persian and Tatar dictionaries.

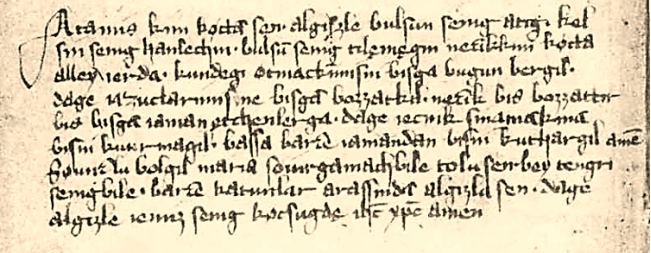

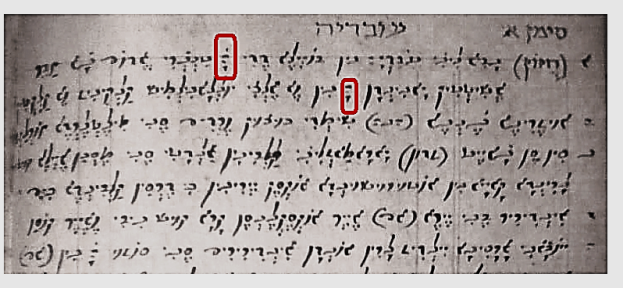

Figure 2. Lord’s prayer from Codex Cumanicus. Atamïz, kim köktäsen, alγïšlï bolsun seniŋ atïŋ! Kelsin seniŋ χanlïχïŋ, bolsun seniŋ tilemegiŋ nečik kim köktä, alley yerdä! Kündegi ötmäkimizni bizgä bügün bergil! Daγï yazuqlarmïznï bizgä bošatqïl, nečik biz bošatïrbiz bizgä yaman etkenlergä. Daγï yekniŋ sïnamaqïna bizni küvürmägil, basa barča yamandan bizni qutχarγïl! Amen! [10]

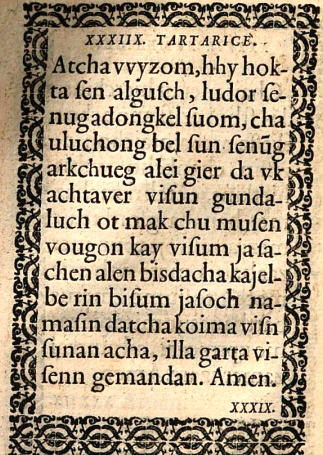

“Tatar” translations of the Lord’s prayer was published in medieval polyglottas. (See Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Lord’s prayer in “Tatar” from a 16th century polyglotta. The text contains some mistakes. For example the handwritten letter M was taken for VV in the first word Atamïz, etc. [11]

There is some evidence that a gospel was translated into the Balkar language at least in the 15th century. [16] Turkic-speaking Armenians living in Ukraine translated the Book of Psalms and produced a number of religious texts in the Armeno-Kipchak language. [17,18]. Several chapters from the Gospel of John were translated into Nogai in the 17th century. [72]

A great number of Bible translations (targums) was made by Turkic-speaking Karaims and even Rabbinic Jews [2, 3, 19] Ebenezer Henderson, a Scottish biblical scholar, describes one of such manuscripts in his book Biblical Researches and Travels in Russia; Including a Tour in the Crimea, and the Passage of the Caucasus. [20]

In the beginning of the 19th century, Scottish missionaries in the North Caucasus translated Gospels, Genesis and Psalms into the local dialect of the Tatar language. They adapted a 1645 Turkish translation of the Bible made by Ali-Bey, and their version was influenced greatly by his work. [4]

Words used to render the concept “God” in the Tatar language

Tatar-speaking nations professed (and still profess) different religions, i.g. Tengrism, Buddhism, Islam, Judaism, Karaism, Christianity, etc. Therefore, while translating the Holy Scriptures for different audiences, they used a number of different approaches to render theonyms.

According to K.Musaev [12], there are three main ways to render the word “God” (Elohim) in modern Turkic languages The Arabic loanword Allah is used mainly in the North Caucasus, Transcaucasia, Crimea, territories near Dnieper, Danube, and Volga. The word Khoda of Persian origin and its derivatives are used mainly in the Central Asia. Whereas nations with a small portion of Muslim population prefer a traditional Turkic name of God, Tengri.

In the present-day Tatar religious and linguistic world-image, the concept «God» is mainly represented by the lexeme الله- Алла / Аллаһы (Alla / Allahi), which is the most common word in the list of names of the Creator. [21] The same word was used also in Old Tatar written texts. For example, it is used very often in Qol Ghali’s Qíssa-i Yosıf, a 13th century Tatar poem (e.g. Аллаһ әмрин сындурмаға қурқарвән — I am afraid to break Allah’s commandment). One more lexeme of the Arabic origin, Иляһе, can be found in the Tatar literature (e.g. Иляһе, хәлемни белүрсән хуш — O God, you see my condition). [22]

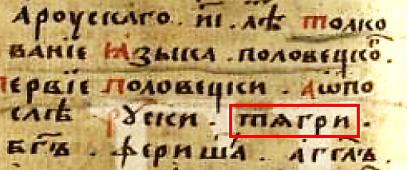

The word Тәңре (Tengri) that comes from the old Turkic language (Tӓŋri ‘sky; God; divine’) is also applied to God in religious and secular writings. This word is mentioned as an equivalent to “God” in Slavic Great Menaion Reader, which contains an entry “ТѦГРИ — БГЪ” i.e. “Tengri — god” in the Polovtsian (Qypchak) — Russian dictionary. [23]

Figure 4. Tengri in The Great Menaion Reader, August, 1542 [23]

Persian loanwords Хода (Khoda) and Ходаwәндә (Khodawende), Turkic Изе (Ize, ‘Master’), and different epithets of God of Arabic origin (i.e. Әхәд, Самәд, Бақи, Зүл-Җәлял, Җәббар, Ғәффар, Раббе, Халиқ, Хақ, etc.) can also be found in Tatar texts. [21]

Tatars living in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania adopted the Belorussian language and translated a number of their religious books into it. It is interesting that they borrowed a Polish-Byelorussian Christian term Pan Boh/Bog (بوَهْ پَانْ, Lord the God) and used it instead of Allah. [24] For instance, Ibrahim Khosenevich’s Kitab says: “bo Pan Boh lubic dobrih 'adpusqliwih” (‘because Lord the God loves merciful ones’) [25]. Pan Boh is a common equivalent of the Hebrew YHWH ELOHIM found in Christian writings.

The theonym YHWH, the sacred Tetragrammaton, was obviously known to Turkic-speaking nations of various religious backgrounds.

Khazars, a Turkic people, were converted in Judaism. A large Khazar community lived in Kievan Rus. In 930, Jews from Kiev wrote a letter in Hebrew[2]. It was a recommendation written on behalf of a certain Jacob bar Hanukah. It mentions names of several members of the Kievan Jewish community, some of which were of Turkic origin. It also has a Turkic runiform inscription, which exact interpretation is still unclear. The letter contained the Tetragrammaton in the form of three letters yod (see Fig. 5).

![]()

Figure 5. Line 20 from the Kievan letter: “…but rather those who remind; and to you will be charity before the YYY your God…” [27]

It is interesting to mention another fact about the use of the Tetragrammaton by Khazars. Slavic Life of Constantine describes Constantin’s mission among Khazars. He is also known as Cyril, a Byzantine Christian theologian and missionary. (He and his brother Methodius were called «Apostles to the Slavs».) While disputing with Jews, he quoted Exodus 19:16 and 34:9. But he did not use the Septuagint, as usual, but read from Aquila’s translation: “And how could Moses in his prayer through the Holy Spirit say with outstretched arms, ‘In the thunder of stones and in the voice of trumpets reveal yourself unto us no more, merciful Lord, but having removed our sins, abide inside us.’ For thus speaks Aquila.” [34]

Figure 6. A quote from Aquila’s translation in The Life of Constantine. [34] YHWH is rendered as Г [ОСПОД]И. i.e. LORD[3]. Aquila’s name is underlined

Aquila was a Jew who translated the Old Testament into Greek (about the 2nd century CE). Unlike the Septuagint, he used the Tetragrammaton written in Paleo-Hebrew letters in the Greek text. Although only fragments of this text remained and the portion containing Exodus 34:9 is missing, the existing abstracts contain the Tetragrammaton in the Greek version at those places, where it can be found in the Hebrew original. We don’t know, whether Cyril pronounced the theonym YHWH on this occasion or not, but it was obviously known to him and his Turkic-speaking listeners, who were readers of Aquila’s version.

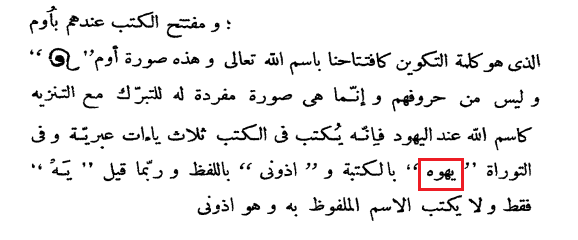

In the beginning of the 11th century, Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni, a Khwarezmian[4] scientist, accompanied Mahmud of Ghazni, a Turkic ruler of the Ghaznavid Empire, in his expeditions to India. As a result, in 1030, Al-Biruni wrote an encyclopedic work Kitāb fī Taḥqīq mā lil-Hind (which is sometimes translated as “Verifying All That the Indians Recount, the Reasonable and the Unreasonable”). In the chapter “Notes on the writings of the Hindus…” he compared religious views of the Hindus with those of Muslims and Jews and described the “Qere and Ketiv” principle applied to the Tetragrammaton. (See Fig.7)

Figure 7. An abstract from Al-Biruni’s Kitāb fī Taḥqīq mā lil-Hind [28]: “The Hindus begin their books with Om, the word of creation, as we begin them with “In the name of God.” [Bismillāhi Ta'ala]. The figure of the word Om is <…>. This figure does not consist of letters; it is simply an image invented to represent this word, which people use, believing that it will bring them a blessing, and meaning thereby a confession of the unity of God. Similar to this is the manner in which the Jews write the name of God, viz. by three Hebrew yods. In the Thora the word is written YHVH [Yahweh] and pronounced Adonai; sometimes they also say Yah. The word Adonai, which they pronounce, is not expressed in writing.” [29]

In the 19th century, Shamil[5], the 3rd Imam of Dagestan, wrote, according to some sources, a song which was sang by murīds. It was translated from Arabic into Russian by Alexander Kazembek. The song contained the following lines:

You are the doors to Jehovah,

Go, save people, and hurry up,

The lost ones have fallen behind,

They have fallen behind the people of God.

For God's sake, and so on. [30][6]

However, the translator did not provide the original text, so it remains unclear what Arabic word was translated as ‘Jehovah’.[7]

While translating the Bible into Turkish, Ali Bey “generally used the Islamic theonyms Allah Teâlâ or simply Allah to translate YHWH, Taŋrı to translate Elohim, and Efendi(m) or Rabb or Rabbî to translate Adonai”. [1]

Based on the analysis of several Turkic translations, K.Musaev lists a number of Turkisms used to render YHWH (Yahweh) [12]. He explains this using the Kazakh language as an example. Kazakh words Ие, Еге (Master, Owner) has a phonetic similarity with Yahweh, therefore, he recommends them (and their analogues in other Turkic languages) to render the Tetragrammaton. For instance, he translates “Sovereign Lord” (Adonai YHWH) in Isaiah 50:4,5 (NIV) as Би Ием (Bi Iem) using the word Би (Lord) as an equivalent for Adonai, and Ие-м (my Master) for YHWH due to its phonetic similarity to Yahweh or Iehova (Jehovah).

Codex Cumanicus

This document contains mainly paraphrases of the Bible and sermons; therefore it is difficult to identify the ways of rendering the Tetragrammaton in this text. However, it should be noted that Turkic words Biy orBey are used as equivalents for the Latin Dominus ‘Lord’, including quotes from the Old Testament, for example: “Söygil Teŋirni, seniŋ Biyiŋni, kerti köŋ lüŋ den, barča džanïŋdan, barčadan küčük džanïŋdan daγï tï nïŋ dan!” (‘Love God, your Lord, with your honest heart, with all your soul, with all your minor soul, and your spirit’) [10]

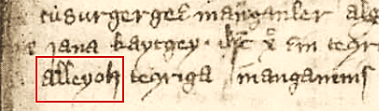

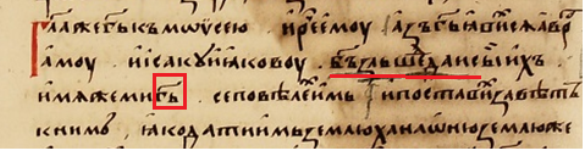

There is also an interesting passage related to the topic of this work with controversial interpretations given by different researchers. (See Fig. 8)

Figure 8. Alleyoh in Codex Cumanicus

G.Kuun [2] interprets it as “Allejoh tengriga (,) inanganmis kin kensi din tengri bisni uretti” putting a footnote “Allejoh ‘laudate Jehovam’” (‘Praise Jehovah’, i.e. Hallelujah). At the same time, A.Garkavets translates this sentence differently: “Alley-oχ Teŋrigä ïnanγanïmïz, kim kensi čïn Teŋri bizni üretti. Amen!”, that is “This is what our faith in God is…” [10].

Armeno-Kipchak writings

Adonai

This word is found in an 18th century Armeno-Kipchak Bible dictionary in the collection of works Vien311. [17]

Biy (Lord)

Psalm 1:6 in the Armeno-Kipchak Psalter (1575/1580): “Zera tanïr Biy yolun artarlarnïŋ, yollarï dinsizlärniŋ tas bolgay.” [18]

Eyä (Lord)

Psalm 77:11 in the Armeno-Kipchak Psalter (1575/1580): “Aŋdïm isin Eyämizniŋ…” [18] This word comes from the same root as the Kazakh term Ие mentioned earlier.

Teŋri

In Armeno-Kipchak texts the word Tengri is usually used as an equivalent for Elohim, but in some verses this term was chosen to render YHWH.

Psalm 14:1 in the Armeno-Kipchak Psalter (1575/1580): “Ayttï harsïz yüräkinä kensiniŋ, ki yoχtur Teŋri.” [18]

Eγovi

An abstract form a sermon based on Malachi 3:10: “Xaysï ki hali dä köplärgä tügälliyir šaytan da etiyir müf tünä čalïšmaχ da öktäm išlär bilä Eγovilär ye mišinä, da χurbanlarïna, da bašχïšlarïna.” [37] This transcription may have appeared due to the influence of Armenian texts, where this form of God’s proper name is used.

Rabbinic Jewish and Karaite writings

Rabbinic Jewish and Karaite writings in Turkic languages mainly follow the ways of rendering the Tetragrammaton in other Jewish targums, including non-translation (original writing) or substitution with Adonai ‘Lord’, H(a), as well as other variants. However, Tatar terms such as Tengri were also used.

Tengri

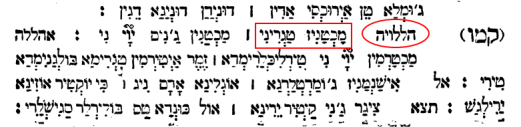

In the Book of Psalms published in Gözleve (1841), the Hebrew expression Hallelujah is often rendered as Maχtaηïz Teηrini ‘Praise Tengri’. (See Fig. 9)

Figure 9. Psalm 146 from the Gözleve (1841) version: הללויה Maχtaηïz Teηrini

Adonai/Adonay

Psalm 71:16 in the translation of the Passover Haggadah, Targum hallel haq-qaṭan, published in Gözleve without date and the name of the translator: “Keleyim bağatırlıqlar bilen, ey Adonay Tañrı; sağındırayım doğruluğuñnı yalğız özüñnüñ.” [38]

Exodus 18:1–27, Parashah Yitro, in north-western Karaim dating back to 1720: “ןידמ ןהכ ורתי עמשיו. Da ešitti Jitro ˪qara tonlusu Midjannyn qajnatasy Mošenin ošol barča ne ki qyldy tenri Mošege da Israelge ulusuna ˪özünün ki čyġardy Adonaj ošol Israelni Micriďan.” [39]

ה H(a)

Ebenezer Henderson, a Scottish Biblical scholar, analyzed a Karaite manuscript of Tanakh and found out: “Wherever the sacred name יהוה occurs in the original, its place is supplied in the version by the abbreviated form ה֜ i. e. הַשֵׁם ‘the Name’.” [20]

Genesis 7:1 in the Bible translation into the northern Crimean dialect of the Karaim language: “Da aytti H Noah-γa: kelgin sen da barča ewŋ ol gemigä ki seni kördüm sadïq aldima ušbu dävirdä.” [2]

Leviticus 1:1 from the translation of the Pentateuch with the parallel Hebrew text (Istanbul, 1832–1835), carried out by Abraham Firkovich, Simha Egiz and Isaac b. Samuel Kohen, in the Turkish language with Kipchak elements: “Da çaġırdı Moşe’ge ohel moʿedden da sevledi H ona deme.” [3]

Numbers 1:1 in the critical edition of the Crimean Karaim Bible: “Da sözlädi H Mošegä yabanïnda Sinaynïŋ ohel moʿeddä¹ birindä ol ekin'i aynïŋ ol ekin'i yïlda čïḳḳanlarïnda² yerindän Mïsïrnïŋ demä.” [40]

Deuteronomy 32:1 in a Halich Karaim manuscript: “… kildi Ha Tenriniz siznin eki ol meleklergeol uspularga…” [41]

Psalm 91:9 in Trakai Karaim: “Ki sen Ha umsunčum jogargy Tenrigä qojduj ornujnu…” [42] (See Fig. 10)

Figure 10. The Trakai Karaim translation of Psalm 91:9. (Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, catalogue number F305–14)

י Ya

Obadiah 1:1 in a Karaite manuscript in Istanbuli Turkish: “Naviliği ‛Obadyah nin boyyle dedi Ya tanŋri ’Edom ğa ḥaber ešittiq yanindan Ya-nin ve elçi.” [43] (See Fig.11)

Figure 11. Obadiah 1:1 in a Karaite manuscript [43]

יוי YWY

This form is often found in targums.

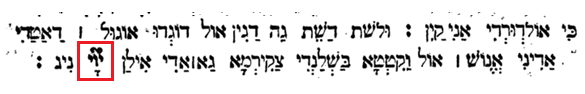

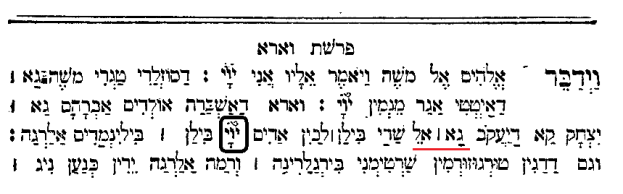

Genesis 4:26 in the Gözleve version of Karaim Tanakh (1841): “וּלְשֵׁ֤ת daShet ga dagin ol dogdu ogul da'atadi adini Enosh. Ol vakiteta bashlandi chakirma ga adi ilan YWY-niпg.” [44] (See Fig.12)

Figure 12. Genesis 4:26 in the Gözleve version (1841) [44]

Leviticus 1:1–3 from Ms. EVR I Bibl. 143 (the National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg) written in 1470–1480s in the Golden Horde Tatar language: “וַיִּקְרָ֖א: Da ündädi Moşeni da sözlädi YWY añar va’da çatırıdan dėmä, דַּבֵּ֞ר: ‘Sözlägin Yisra’el ulanlarına da aytqaysın alarġa, “Adam ki keltirsä sizdän qorban YWY-ġa tuvardan, sıġırdan da qoydan kėltirgäsiz qorbanıñıznı. אִם: Ėgär ‘ola ėsä qorbanı sıġırdan bütün ėrkäk keltirgäy anı ėşiginä va’da çartırınıñ keltirgäy anı qabul köñlinä alnına YWY-nıñ.” [45] (See Fig. 13)

Figure 13. Leviticus 1:1–3 from Ms. EVR I Bibl. 143 [46]

יהוה YHWH

While analyzing the manuscript mentioned above, E.Hendersen wrote, “The name צִדְקֵֽנוּ יהוה Jehovah our Righteousness (Jerem. xxiii. 6, and xxxiii. 16) is … left untranslated.” [20][8]

The influence of Turkic targums on 15th century Slavic translations of the Pentateuch

In 1842 and in 1860, Alexander Vostokov and Alexander Gorsky, respectively, found the so-called Edited Slavonic-Russian Pentateuch, which contained glosses and emendations related to the Masoretic Text and Jewish Biblical exegesis. As it has been found, these versions were edited via “the obvious intermediary translations of the Masoretic text into a Turkic language, more precisely Old Western Kipchak which was close to the language of the 1330 copy of the Codex Cumanicus; to the Mamluk-Kipchak of the Egyptian texts of the 13th–15th centuries; and to the Armenian-Kipchak of the Galician and Podolian MSS of the 16th–17th centuries; and finally to Karaim, the language of the East European Karaites who lived at that time in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.” [19]

Some of these glosses were related to rendering the Tetragrammaton in the book of Exodus. Some of them were analyzed by B.Uspensky. [47] (See Fig. 14)

Figure 14. Exodus 3:14,15 in the Edited Slavonic-Russian Pentateuch. [48] The marginal gloss “adonai” corresponds to the expression “Lord the God” (YHWH Elohim in the original text)

It should be noted that glosses and emendations in the Slavic texts corresponded to names and epithets of God in Turkic targums. [19] (See Fig. 15)

A.

B.

Figure 15. A — Exodus 6:3 in the Edited Slavonic-Russian Pentateuch [48]. “And I appeared unto Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, by the name of El-Shadday (underlined), but by my name LORD (encircled) was I not known to them.” B — Exodus 6:3 in the Gözleve version (1841). “Da ašbara oldim Avrahamga Yitsḥaqqa da Ya‘aqovga El-Šadday (underlined) bilan lakhin adim YWY (encircled) bilan bilinmadim aladga.” [19]

Translations of the Bible into Tatar made by Scottish missionaries in the 19th century

C.Frazer’s translation of the Book of Genesis

Allah

Some researchers concluded, that Ali Bey, the translator of the Turkic Bible, as a rule, used the Islamic theonyms Allah Teâlâ or simply Allah to translate YHWH [1]. Charles Fraser, in general, followed this approach. For instance, the first occurrence of YHWH in the Bible is in Genesis 2:4. Fraser translated this verse as follows: “Köklärniŋ vä yerniŋ yaratġanları zamānda āṣılları bu edi: Allah Teŋri yerni vä köklärni yaratġan kündä.” [4]

Rabb

Genesis 4:1 Andan Ādem ḫatunı Ḥavānı bildi, vä ol ḥāmilä bolıp Ḳāyınnı doġurdı vä ayttı: ‘Bir ādam yaʿnı̇̄ Rabbnı ḳazandım’.” [4]

Teŋri

Both Ali Bey and Fraser used the Turkic word Teŋri as an equivalent for Elohim. However, there were some exceptions, when Teŋri was used by Fraser to translate YHWH. For example, in Genesis 7:1 “Vä Teŋri Nūḥġa ayttı: ‘Sen vä barça eviŋ sefı̇̄nä içinä kir, zı̇̄rā bu dahırda seni aldımda ṣādıḳ kördim’.” [4]

يهو Yahu

This transcription of the Tetragrammaton can be found in the Tatar translation of Genesis in the following verses: 4:26, 10:8, 11:4, 21:33, 22:14, 24:3, 24:7, 28:21.

For instance, Genesis 4:26: “Vä Şeṯġä daḫı bir oġul doġdı, vä anıŋ adın Enōş ḳoydı. Ol zamān Yāhūnıŋ adı istidʿā bolunmaġa başlanʿdı.” [4]

Translation of the Book of Psalms (Astrakhan, 1815)

A.Glashev analyzed the text of the Tatar translation of Psalms published in Astrakhan, in 1815. According to his conclusions (along with A.Garkavets), Tengri is used to translate the word “God”, and Biy is an equivalent for Lord. He also states that when the Scriptures spoke about God in general, the translators used the word Allah. But if the biblical text speaks of the God of Israel, the word Tengri is used. [12]

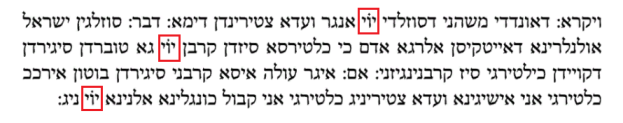

Modern Tatar translations

Modern translation of the Bible in the Tatar language produced by the Institute for Bible translation, as a rule, uses the word РАББ (Lord) as the equivalent for YHWH. A footnote to Genesis 2:4 says: “РАББЫ: Яһүд телендәге «Яһвә» сүзе (Аллаһының Үз исеме, «бар булу» фигыле белән бәйле) «Иске Гаһед»нең әлеге басмасында «Раббы» дип бирелә. «Яһвә» исемен кычкырып әйтергә ярамаганлыктан, тора-бара аның урынына «Адонай» (Хуҗам) сүзен куллана башлаганнар. Грек телендә язылган Инҗилдә «Яһвә» һәм «Адонай» исемнәре «Кюриос» (Раббы, Хуҗам) дип тәрҗемә ителгән, һәм шушы сүз Аллаһыга карата да, Гайсә Мәсихкә карата да кулланыла.” (The Hebrew word «Yahweh» (the proper name of God meaning «the one who exists») in this edition of the Old Testament is referred to as «Lord». Since the name «Yahweh» could not be pronounced loudly, the word «Adonai» (Master) was used instead. In the New Testament written in Greek, the names «Yahweh» and «Adonai» are translated as «Kurios» (Lord, Master), and this word is used in relation to both God and Jesus Christ). [52] The same approach is applied by translators of the book of Jonah into the Siberian Tatar language, who wrote in a footnote to Jonah 1:1 that they use the term РАППИ to translate YHWH (“Яхве”).

Conclusions

Translators of the Holy Scriptures into the “Tatar” language used several approaches to render the theonym YHWH depending on their religious background. For instance, translators of Rabbinic Jewish and Karaim versions prefer the original writing or acronyms for God’s name used in Judaism. Translators with the Christian background prefer semantic translation and transliteration/transcription. At that, only translators of the modern versions are consistent in using one equivalent for rendering the Tetragrammaton (usually it is an Arabic loanword RABBI). There is also an interesting approach proposed by K.Musaev to translate the theonym YHWH using equivalents with phonetic similarity (i.e. Kazakh Ие ‘Master’, Tatar Ия, Armeno-Kipchak Eyä).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT. The author would like to thank Dr. Pavlos D. Vasileiadis, a post-doc researcher in the Biblical Literature and Religion Department, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece, for his kind help and consultations.

Appendix A.

The use of the theonym Егова “Jehovah” in the legislation of the Russian Empire concerning Jews and Karaims

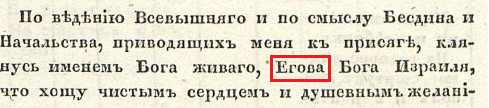

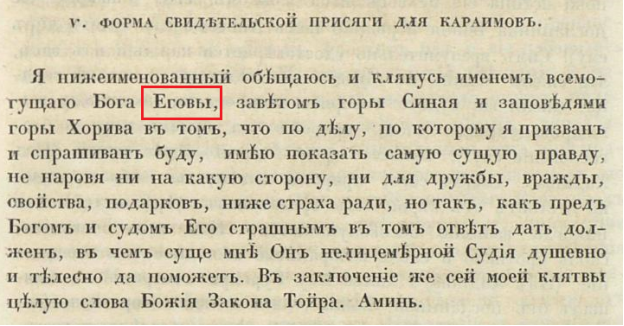

Several laws and legal enactments issued by the Government of the Russian Empire contained texts of oaths for Jews and Karaims. The proper name of God in the form of Егова “Jehovah” was used there. Two examples can be seen below (Fig. 1 and 2)

Figure 1. An oath for members of the Jewish Prayer Society: “… I swear by the name of the living God, Jehovah, God of Israel…” [49]

Figure 2. Sworn testimony for Karaims: “… I swear by the name of the Almighty God Jehovah…” [50]. At that, the authors of this law require to translate this oath into the Tatar language with Hebrew letters.

Appendix B.

Psalm 91 in several Turkic versions.

|

|

Trakai Karaim [42] |

Armeno-Kipchak [18] |

Kryashen Tatar [51] |

Modern Tatar [52] |

|

|

Olturußču sijinčinda jogargy Tenrinin kölägäindä küčlü tenrinin sijinadir |

Kim dä tïnïptïr bolušluχundan Biyiktäginiŋ, kölegäsi tibinä Teŋriniŋ köktä tïngay. |

Жугарыгы (Ходай) булышыб торган кеше, Кюктяге Алланын бӧркяӱе эченя урыннашыр. |

Аллаһы Тәгалә яклавындагы кеше кодрәтле Затның ышыгында урын табар. |

|

|

ajtamin Haga išančim da bekligim; Tenrim išanamin anar |

Aytkay Eyämizgä:«Yöpsünövlümsen, umsam menim Asduadz, da men umsanïrmen saŋa. |

Ходайга ӓйтер: Жаклаучым, Сыйындырыучым, ышаныб торган Аллам дирер. |

Раббыга әйтер ул: «Сыену урыным, кальгам-ныгытмам, өмет баглаган Аллам — Синдер» |

|

|

ki ol qutcharir seni tuzachtan ilinädogon ölättän da qawšarlichtan |

Ol χutχargay meni avïndan ulavučïnïŋ da seskändirüči sözündän». |

Сине Ул тотарга жӧрӧӱченен тозагыннан, ӓляк сюздян коткарыр шул. |

Раббы сине аучы тозагыннан да, үләт зәхмәтеннән дә коткарыр, |

|

|

hašgachasi bila qalqanlar seni da škinasi tübünä sijinirsin qalqan da kübä kertiligi anin |

Arχasï üsnä kensiniŋ kötürgäy seni, kölegäsinä χanatlarïnïŋ umsangaysen. Necik yaraχ, čövräŋa bolgay seniŋ könülükü anïŋ. |

Сине жилкясе белян каблаб торор, канатлары астында курыкмый торорсыҥ; Анын чынныгы каблауыч кюк сине жабыб торор |

сине канатлары астына алып каплар, шунда сыенып хәвефсез яшәрсең. Аның тугрылыгы синең өчен калкан, кальга дивары булыр |

|

|

Qorchmassyn qorchubdan kečänin ochtan učadogon kündüz |

Xorχmagaysen sen χorχusundan kečäniŋ da ne oχtan, ki učar kündüz. |

Тӧндяге куркынычтан, кӧндӧз атылыб килгян уктан |

Төнлә ябырылып килгән дәһшәт тә, көн яктысында очкан уклар да, |

|

|

ölättän tumanda ürüjdogon kesmäktän talejdogon tüš vachtlarda |

Nemä bar, ki učar χaraŋγuda, yaŋïldïrmaχïndan šaytannïŋ yarïmkündä. |

карангыда була торган зыяннан, чирдян, тӧш багытындагы женнян курыкмассыҥ. |

караңгыга төренеп йөри торган үләт зәхмәте дә, көндезен кырган мур да куркыта алмас сине. |

|

|

tüsä son janijdan min da tümän on janijdan saja jaman jubumast |

Tüssün yanïŋdan seniŋ miŋlär da tümänlär oŋuŋdan seniŋ, ki saŋa nemä yovuχlanmagaylar. |

Сул жагыҥда меҥняб жыгылырлар, уҥ жагыҥда ун меҥняб кырылырлар, сиҥа жакыннашмас та. |

Янәшәңдә — мең кеше, уң тарафыңда ун мең кеше кырылып ятса да, сиңа үлем янамас. |

|

|

ančech közlärij bila baharsin da töläwin raša'larnin körärsin |

Tek yalγïz közläriŋ bilä baχkaysen sen, tölövün yazïχlïlarnïŋ körgäysen, |

Син тик кюз салыб кна усалларга кайтарылганны кюрерсеҥ |

Яман бәндәләрдән үч алынуын син читтән торып тамаша кылырсың. |

|

|

ki sen Ha umsunčum jogargy Tenrigä qojduj ornujnu |

zera sen, Biy, umsamsen menim. Biyiklängännï ettiŋ kensiŋä išanč, |

Эй Ходай, ышаныб торганым Син диб ӓйтеӱеҥ белян, |

Сыену урыным — Раббыда! Ышыклыгың Аллаһы Тәгаләдә булганга, |

|

|

siltav etilmäst saja jamanlich da chastalich jubumast čatirija |

yetišmägäy saŋa yamanlar, da χïyïn yovuχlanmagay öviŋä seniŋ. |

Жугарыгыны син сыйындырыучыҥ иттеҥ шул. |

синең башыңа явызлыклар төшмәячәк, чатырыңа афәтләр якынлашмаячак. |

|

|

ki malaklarin simarlar saja saqlama seni bar jollarijda |

Frištälärinä kensiniŋ sïmarlaptïr seniŋ ücÿün saχlama seni barča yollarïŋa se [ni]ŋ. |

Ӓр бер жӧрӧшӧҥдя сине Ӱз Пяриштяляреня саклатыр шул. |

Чөнки һәр йөргән юлыңда сине сакларга дип, Үзенең фәрештәләренә Ул боерык биргән. |

|

|

qijasa uvučlar üstünä eltirlär seni magat sürünürz tacha ajagij |

Biläkläri üsnä kensiläriniŋ kötürgäylär seni, ki heč urunmagay taška ayaχlarïŋ seniŋ. |

Сине алар кулларына кютяреб барырлар, аягыҥ ташка сӧртӧнмяс. |

Юл ташына абынып егылмассың: фәрештәләр сине кулларына күтәреп алыр. |

|

|

qart arislan üstünä da azdaga üstünä ürürsün basarsin igit arislanni da azdagani |

Üsnä izÿniŋ da karpnïŋ yürügäysen sen, ayaχ tibinä baskaysen aslannï da adždahanï. |

Аспидъ василискъ дигян жыланнарны жянчерсеҥ, арысланны, аждагыны табтарсыҥ. |

Син арыслан вә зәһәр еланнар өстенә басып үтәрсең, яшь арыслан вә аждаһаларны таптап изәрсең. |

|

|

kim meni sübsä da qutcharirmin ani da kiplärmin ani kim bilsä emimni |

Zera maŋa umsandï, daχutχarïyïm anï, kölegä bolïyïm aŋar, ki tanïdï atïmnï menim. |

Миҥа ӧмӧт тотканы ӧчӧн аны коткарырмын, исемемне белгяне ӧчӧн аны каблаб торормын. |

«Мине сөйгән затны Мин коткарырмын, исемемне күңелдә йөрткәне өчен, аның яклаучысы булырмын, — дияр Раббы. – |

|

|

čagirsa maja da karub berirmin anar birgäsinä men bolurmin tarlichta kutcharirmin ani da sijlarmin ani |

Sarnagay alnïma, da men išitkäymen aŋar da χatïna bolgaymen tarlïχïna. Xutχargaymen da haybatlï etkäymen anï, |

Миҥа тилмерся аны эшетермен; кайгысында булышырмын; аны аралаб алырмын; аны данналдырырмын. |

Ул мине дәшеп чакырыр, һәм Мин аңа җавап бирермен, кайгылы чагында янында булырмын, коткарып, аны данга күмәрмен; |

|

|

uzun künlärdän tojdururmin ani da körgüzürmin ani jarligaimni |

uzun künlär bilä toldurgaymen da körgüzgäymen aŋar χutχarmaχïmnï menim. |

Аны кюб жяшятермен, коткарганымны аҥар кюргязермен. |

гомерен озын кылып, коткару бүләк итәрмен!» — дияр. |

References:

- Bruce G. Privratsky. Kitabı Mukaddes’in Türkçe Tercümelerinin Tarihçesi, 16–21 yy. Bütün baskıların listesi, tarihsel açıklamalar ve araştırma önerileriyle https://historyofturkishbible.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/tc3bcrkc3a7e-km-tarihi_version-s.pdf

- Jankowski, H. A Bible Translation into the Northern Crimean Dialect of Karaim. Studia Orientalia Electronica, 82, 1–84. Retrieved from https://journal.fi/store/article/view/45110

- Jankowski, H. Crimean Turkish Karaim and the Old North-Western Turkic tradition of the Karaites. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 68 (2), 199–214 (2015)

- Гаркавец А. Musanıŋ ilk kitabı. Кыпчакское Бытие. Перевод Чарльза Фрейзера. Карас, Астрахань, Оренбург, 1803–1819. Напечатано Джоном Митчелом. Шотландское Миссионерское Общество. Астрахань, 1819. — Алматы: Баур, 2015. — 140 стр.

- Thomas Hartwell Home. An Introduction to the Critical Study and Knowledge of the Holy Scriptures: Volume 2. 1835–700 p.

- Глашев А. А. Евангелие и Псалтырь на тюрки, изданные в Каррасе и Астрахани в 1806–1825 гг. //Перевод Библии как фактор развития и сохранения языков народов России и стран СНГ: проблемы и решения. М., 2010. С. 307–318

- Мусаев К. Об истории и проблемах перевода Библии на тюркские языки // Перевод Библии в литературах народов России, стран СНГ и Балтии. М., 1999. с. 161–171

- Tekin, Talat: Irk bitig: (the book of omens).- Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1993. — 133 p.

- Малов С. Е. Памятники древнетюркской письменности: Тексты и исследования / Акад. наук СССР. Ин-т языкознания. — Москва; Ленинград: Изд-во Акад. наук СССР, 1951. — 452 с.

- Гаркавец А. Н. Codex Cumanicus: Второе полное издание. — Алматы: Алматы-Болашак, 2019. — 1360 с.

- Specimen quadraginta diversarum atque inter se differentium linguarum & dialectorum; videlicet, Oratio Dominica, totidem linguis expressa. 1593. — 46 p.

- Мусаев К. Проблемы перевода библейских имен Бога (на материале тюркских языков). // Перевод Библии. Лингвистические, историко-культурные и богословские аспекты. М., 1994. С. 170–182

- Иеромонах Иннокентий Кильдеев. Проблема имени Божьего в разных языках и культурах. URL http://tatar.orthodoxy.ru/?page_id=4376 (дата обращения: 29.03.2020).

- Шихалиева Сабрина Ханалиевна Имена Бога в новом Завете и проблема их перевода // Гуманитарный вектор. Серия: Филология, востоковедение. 2013. № 4 (36). URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/imena-boga-v-novom-zavete-i-problema-ih-perevoda (дата обращения: 29.03.2020).

- Pavlos Vasileiadis. Aspects of rendering the sacred Tetragrammaton in Greek, Open Theology, Vol. 1 (2014), pp. 56–88.

- История Кабардино-Балкарии: Учеб. пособие для сред. шк. / [Б. М. Керефов и др.]; Под общ. ред. Т. Х. Кумыкова, И. М. Мизиева. — Нальчик: Эльбрус, 1995. — 382 с.

- Александр Николаевич Гаркавец. Кыпчакское письменное наследие. Том І. Каталог и тексты памятников армянским письмом.– Алматы: Дешти Кыпчак, 2002.– 1084 стр.

- Armenian-Qypchaq Psalter written by deacon Lussig from Lviv, 1575/1580 / Edited by Alexander Garkavets and Eduard Khurshudian.— Almaty: Desht-i Qypchaq, 2001.

- Грищенко А. Правленое славяно-русское Пятикнижие XV века: предварительные итоги лингвотекстологического изучения. М.: Древлехранилище, 2018. — 176 с.

- Henderson E. Biblical Researches and Travels in Russia; Including a Tour in the Crimea, and the Passage of the Caucasus (etc.). Published by James Nisbet, 1826. — 539 p.

- Мирхаев Р. Ф., Гумеров И. Г. Татарская религиозно-языковая картина мира: эволюция культурных и духовно-ценностных ориентиров — Казань: ИЯЛИ, 2017. — 120 с

- Кул Гали. Кысса- и Йусуф: Поэма. — Казань: Татар. кн. изд-во, 1989. — 220 с.

- Син. 997. Минеи-Четьи митрополита Макария, август. 1542 г. URL: https://catalog.shm.ru/entity/OBJECT/178447?album=622494765&index=91 (дата обращения: 29.03.2020).

- Shirin Akiner. Religious Language of a Belarusian Tatar Kitab: A Cultural Monument of Islam in Europe. With a Latin-Script Transliteration of the BL Tatar Belarusian Kitab. Mediterranean Language and Culture Monograph Series, vol. 11. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. 2009. Pp. xxvii + 457

- Китаб Ибрагима Хосеневича 1861 года из собрания Национальной библиотеки Республики Беларусь как исторический источник: дипломная работа / Кевра Инна Чеславовна; БГУ, Исторический факультет, Кафедра источниковедения; науч. рук. доцент Белявский А. М. http://elib.bsu.by/handle/123456789/117636 (дата обращения: 29.03.2020).

- Marcel Erdal, 'The Khazar Language,' in Peter B. Golden, Haggai Ben-Shammai, András Róna-Tas,(eds.), The World of the Khazars: New Perspectives,Brill, 2007 pp.75–108.

- Golb, Norman and Omeljan Pritsak. Khazarian Hebrew Documents of the Tenth Century. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1982–166 p.

- Kitāb fī Taḥqīq mā lil-Hind (Al-Bīrūnī's India) Arabic Text. An Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India about 1030 AD. Revised by the DMO from the oldest extant manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Schefer 6080). Osmania Oriental Publication Bureau, Andhra Pradesh, India, 1958. — 699 p.

- Bīrūnī, Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad, Alberuni's India London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1910.Electronic reproduction. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y.: Columbia University Libraries, 2006. — 408 p.

- Казембек А. Мюридизм и Шамиль. — Русское Слово. 1859, № 12. С.241

- Кавказ: Адаты горских народов. — Нальчик, 2010. Вып. IV — 384 с.

- Jean Chardin. Voyages de monsieur le chevalier Chardin en Perse et autres lieux de l’Orient, Amsterdam, Jean-Louis de Lorme, 1711–463 p.

- G. Gertoux. The Name of God Y. e H. o W. a H Which is Pronounced as it is Written I_E h _ o U_A h. University Press of America. 2002. Pp.47-79.

- Marvin Kantor. Medieval Slavic Lives of Saints and Princes. The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 1983. Pp.25–81.

- Василиадис П. Д., Борщевский И. С. Aspects of Rendering the Sacred Tetragrammaton in Medieval Slavic Religious and Secular Texts // Филология и лингвистика. — 2019. — № 3. — С. 1–16. — URL https://moluch.ru/th/6/archive/144/4511/ (дата обращения: 30.03.2020).

- CODEX CUMANICUS. Ed. By G.Kuun. Budapest, 1886.

- Конгрегация армянских мхитаристов, г. Вена, № 468: Сборник Хачереса, сына Оксента. Христианские каноны и прочие сочинения. // Гаркавец Александр Николаевич. Кыпчакское письменное наследие. В 3 томах. — Изд. 2-е, переработанное и дополненное. Том I. Армянописьменные памятники, хранящиеся в Австрии, часть 1. — Алматы: Баур, 2017. — 810 стр.

- Jankowski, H. Literatura krymskokaraimska. Przegląd Orientalistyczny Nos 1–2, pp. 50–68.

- Németh, Michał. An Early North-Western Karaim Bible Translation from 1720. Part 1. The Torah. Karaite Archives 2 (2014), pp. 109–141

- “The Book of Numbers.” The Crimean Karaim Bible: Vol. 1: Critical Edition of the Pentateuch, Five Scrolls, Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Daniel, Ezra and Nehemiah. Vol. 2: Translation, by Henryk Jankowski et al., 1st ed., Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2019, pp. 219–292. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvh4zgsw.11. Accessed 29 Mar. 2020.

- Olach, Z. Numerals in Halich Karaim Bible texts. Studia Uralo-Altaica, 49, 371–380. Retrieved from https://ojs.bibl.u-szeged.hu/index.php/stualtaica/article/view/13688 (дата обращения: 30.03.2020).

- Csató, É. (2011). A typological coincidence: Word order properties in Trakai Karaim biblical translations. In Puzzles of language: Puzzles of language. Essays in honour of Karl Zimmer. / [ed] Eser Eser Erguvanlı Taylan & Bengisu Rona, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2011, p. 169–186

- Shapira, Dan. A New Karaite-Turkish Manuscript from Germany: New Light on Genre and Language in Karaite and Rabbanite Turkic Bible Translations in the Crimea, Constantinople and Elsewhere. Karaite Archives 2 (2014), pp. 143–176

- Targum Tora bi-Lshon Tatar. Гёзлёв (Евпатория) 1841–400 стр.

- Lily Kahn. Jewish Languages in Historical Perspectives. Brill 2018 — p.45

- A. Harkavy & H. L. Strack. Catalog der hebräischen Bibelhandschriften der kaiserlichen Öffentlichen Bibliothek in St. Petersburg. Erster und zweiter Teil. St. Petersburg, 1875 — p. 167

- Успенский Б. А. Имя Бога в славянской Библии (К вопросу о славяно-еврейских контактах в Древней Руси). Вщпросы языкознания, № 6, 2012. Стр. 93–122

- Фонд 113. Собрание рукописных книг Иосифо-Волоцкого монастыря. Рукопись № 47. Книги Ветхозаветныя Моисеевы: Бытия, Исход и Левит. XV век.

- Полное собрание законов Российской империи. Собрание 2. Том 10 — Санкт-Петербург: 1855. — p. 60

- Леванда В. О. Полный хронологический сборник законов и положений, касающихся евреев, от Уложения царя Алексея Михайловича до настоящего времени, от 1649–1873 г.: Извлеч. из пол. собраний законов Рос. империи. — Санкт-Петербург, 1874. — 1158 с.

- Молитвенник на кряшенском языке. URL: http://daniilcenter.ru/images/stories/dvizenie/kryashen-spusk.pdf (дата обращения: 30.03.2020).

- Татар теле Изге Язма: Иске Гаһед (Тәүрат, Зәбур, пәйгамбәрләрнең язмаларын). Яңа Гаһед (Инҗил-шәриф). Татар теле Изге Язма: Иске Гаһед (Тәүрат, Зәбур, пәйгамбәрләрнең язмаларын). Яңа Гаһед (Инҗил-шәриф). URL: http://ibt.org.ru/bible (дата обращения: 30.03.2020).

- Йунуспәйғәмпәрнеңкитабы (себертатарәмурыстелтә). URL: http://ibt.org.ru/ru/media?id=SBT (дата обращения: 30.03.2020).

[1] To compare the text of Psalm 91 in several ancient and modern “Tatar” languages, see Appendix B.

[2] According to some scholars, the letter was sent not from Kiev, but to Kiev [26].

[3] For detailed analysis of rendering the Tetragrammaton in Slavic texts, see [35]

[4] Khwarazm is a region located on the territory of modern-day western Uzbekistan and northern Turkmenistan

[5] Shamil’s father was a Kumyk and his mother was an Avar.

[6] According to some sources, a 19th century Circassian tariqa admonition written in Arabic contained the Tetragrammaton in the form of Yahweh. [31]

[7] A 17th century traveler Jean Chardin links Hu, the name for God in Sufism, to Jehovah [32]. The relation between the term Hu and theonym Jehovah was discussed in details by G. Gertoux. [33]

[8] Examples of the use of the theonym Jehovah in the legislation of the Russian Empire concerning Jews and Karaims are listed in Appendix A.