Introduction

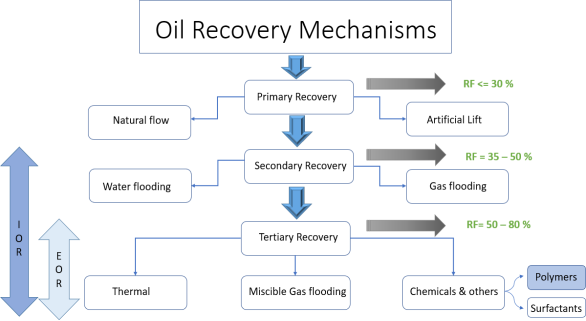

Oil recovery mechanisms can be broadly categorized into three stages: primary, secondary, and tertiary oil recovery. These stages have historically represented the sequential progression of reservoir production. Primary production, the initial stage, relies on the inherent displacement energy within the reservoir to extract oil. As primary production declines, the secondary mechanisms come into play. Traditionally, secondary recovery methods include water flooding, pressure maintenance, and gas injection. Nowadays, water flooding has become synonymous with secondary recovery techniques. Tertiary recovery, the third stage, is implemented after water flooding. In cases where secondary recovery is no longer economically viable, tertiary recovery methods are employed. These methods encompass the use of miscible gases (such as carbon dioxide, hydrocarbon, or nitrogen), chemicals (including polymers, surfactants, and alkaline substances), thermal energy (in the form of cyclic steam, steam flooding, and in-situ combustion), as well as emerging approaches like Low-Salinity Water Injection (LSWI), all aimed at achieving enhanced oil recovery (EOR) [1]. Figure.1 shows the various recovery methods used throughout the duration of an oil reservoir's life.

Fig. 1. Illustration of the different Oil recovery processes

Low salinity water (LSW) flooding, which includes brine dilution to lower the total salinity of the water flooding, has been found to be more effective than high salinity water recovery processes in improving oil recovery. In order (LSW) flooding is an improved oil recovery process that includes injecting water with low soluble solids concentrations into a reservoir. Laboratory experiments have shown its potential for enhancing oil production. In contrast to traditional water injection, Low salinity water (LSW) flooding would affect the wettability of reservoir rock to enhance the recovery of oil. It is often used as a tertiary oil recovery method and offers tremendous potential for oilfield development. The laboratory application into a core for salinity water injection was started in 1967 by Bernard. There was extensive laboratory scale research at that time. The number of experiments and studies has significantly increased. Many laboratory investigations have indicated that using low salinity water improves the recovery oil in both sandstone and carbonate reservoirs [3].

Factors influencing the low salinity process

Key Factors Affecting the Low Salinity Process as a result, under certain conditions, low salinity water may effectively improve oil recovery. The following are the specified parameters for identifying low-salinity impacts: (1) Reservoir lithology, such as clay minerals, especially kaolinite, was found in the formation. However, there was no sign that the absence of clay had a positive effect on the clastics. (2) Composition of Crude Oil: There are polar components in crude oil, but there is no advantage to using depolarized or synthetic oils. The wettability of rock may be altered by surface-active substances that exist naturally, such as resins or asphaltenes [4]. (3) Connate Water Presence: During LSW injection, oil recovery is heavily affected by the initial characteristics of the reservoir, especially the saturation of the connate water, the salinity of the connate water, and the physical properties of the rock [5]. (4) The Divalent Ion Content of formation Water: For carbonate cores, clastic need the presence of divalent ions Mg+2, Ca+2, and So4 −2. In lab tests, injection of divalent ion-rich brines was observed to stop oil production [4].

Proposed mechanisms for low salinity water (LSW)

The process behind enhanced oil recovery through LSW flooding in carbonates is relatively easier to comprehend than that in sandstones, since most authors agree on wettability changes. Austad and colleagues conducted significant research that demonstrated the feasibility of adjusting wettability and improving oil recovery from carbonate rocks by changing the ionic content of the water injection [6].

Interaction between Rock and Fluid: Wettability Alteration

Carbonates are often thought of as oil-wet substances. This is because, at pH levels lower than 8–9, the surfaces of carbonates are positively charged. The presence of carboxylic, stearic, and fatty acids gives crude oil a negative charge, which attracts carbonates at the COBR interface and causes oil-wetting. Altering the wettability of carbonates from oil-wet to water-wet is favorable for IOR [6]. Electrostatic interactions, there are two distinct wettability-altering processes associated with the electrostatic interaction in the DVLO-affected carbonate (COBR): 1) multivalent ionic exchange (MIE); 2) expansion double layer (EDL) [7].

- Multivalent Ionic Exchange (MIE)

Wettability modification is the main and more preferable approach for increasing the recovery of oil in carbonate rocks using low salinity water (LSW) flooding [2]. The modification of the wettability phenomena may be caused by a change there in surface charge of the rock as a consequence of organic material desorption or dissolution [4]. The increased sulphate attraction toward the surface of carbonate with increasing temperature was found to be the cause of sulphate catalytic activity at high temperatures. The increase in sulphate attraction instantly alters the rock charge from positive to negative, creating carboxylic group repulsion and turning the structure water-wet. The addition of cationic surfactants and sulphates reduces interfacial tension and alters wettability. Consequently, increasing the system's temperature not only decomposes the carboxylic group but also enhances sulphate adsorption on the surface of rock, hence improving water retention. They indicated that the advantage of sulphate as a wettability modifier has restrictions based on the temperature and salinity of the initial brine, since the concentration of 𝐶𝑎2+in the connate brine must be recognized with certainty to avoid 𝐶𝑎𝑆𝑜4 precipitating [7].

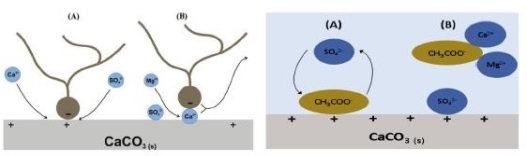

Fig. 2. (1) Proposed mechanisms for modification of wettability in carbonate rocks. (2) Proposed mechanisms for modification of wettability by EWI in carbonate rocks [7]

Injecting water with 𝑆𝑜4 −2, 𝑀𝑔2+, and 𝐶𝑎2+ at 90 °C may change carbonate rocks' wettability. Figure.2 shows both hypothesized processes for modifying carbonate rock wettability. It was assumed by the authors that when temperatures increase, sulphate becomes more attracted to the rock surface, resulting in sulphate absorption. Simultaneously, 𝐶𝑎2+ adsorption increases as the original positive charge of the rock decreases. As a result, there are more excess 𝐶𝑎2+ions on the surface, which interact with the carboxylic substance and cause some of them to be released. In addition, when the temperature increases, 𝑀𝑔2+ gets increasingly more active, 𝐶𝑎2+ is replaced with 𝑀𝑔2+, and sulphate loses activity as a result of its interaction with 𝑀𝑔2+ [8].

- Expansion Double Layer (EDL)

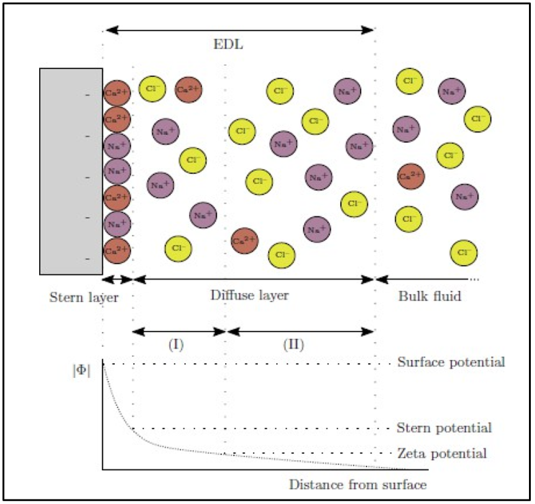

A potential is generated at the interface between a charged surface and a solution. This conceivable variation has two levels, each of which has its unique characteristics simply because it is multi-layered. The term «electrical double layer» describes this phenomenon (EDL). Figure 3 illustrates the simplified diagram of the expansion double layer. The EDL has two levels, which are: a) Stern layer: A thin, dense layer near the surface layer, about 1 nm thick. There are no moving ions in this layer. This layer is where most of the possible drops will happen. b) Diffuse layer: A layer whose thickness changes from 1 to 500 nm based on how much the double layer expands. Electrostatic forces bring together ions that have the opposite charge as the charged surface. At the same time, diffusivity caused changes in osmotic pressure work against this and try to make the concentration of ions the same as the concentration of the bulk solution. A comparable force competition arises for ions that have the same charge as the surface. The electrostatic forces reject those ions from the surface. Repulsion is neutralized by back diffusion from the bulk solution.

Figure 3 a schematic representation of the electrical double layer that forms on clay with a negative surface charge (the Stern layer). Below the graphic model is a drawing showing the potential in relation to the bulk fluid as a function of distance from the clay surface. Ions further away from the charged surface often travel faster than ions closer to the charged surface. The Stern layer could get thinner, but the diffuse layer will get thinner more slowly. The thickness of the EDL is affected by the fluid's ionic strength. The electrolyte concentration in the bulk water solution decreases during low-salinity water (LSW) flooding, causing the EDL to expand. This is especially how the diffuse layer will act. However, the EDL thickness will be greatly reduced with an increase in electrolyte concentration. Compared to single-valence ions, multivalence ions have a greater influence on the expansion of double layers [10]. A reduction in ionic strength often results in EDL expansion, which enhances water wetting as a result of increased separation between the calcite and the oil. According to the DLVO hypothesis, the total frictional force pressure at the COBR contact becomes favorable (negative) when the polarities of the brine rock surface charge differ from those of the brine-crude oil surface charge. This would cause the water film to disintegrate, resulting in oil wetness.

Fig. 3. A schematic of the electrical double layer (EDL)

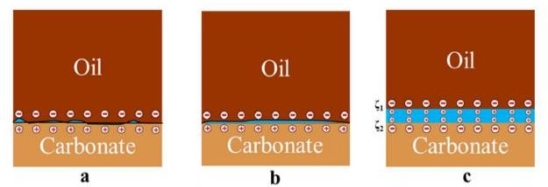

Figure 4 Illustrates the variation in the COBR interface region potential as brine salinity decreases. When an oil molecule with a negative charge comes into contact with a positively charged carbonate surface, the carbonate changes from being oil-wet to being mixed-wet, as shown in Figures.4a, 4c show that when the polarity of the oil-brine interface and the brine-rock interface are the same, there is a force pushing the oil away from the rock surface. This causes the expansion double layer (EDL) to expand at the rock-brine and crude oil-brine interfaces. This makes the water film thicker and changes the surface from being oil-wettable to water-wettable [11].

Fig.4. The change in the COBR contact surface potential as brine salinity drops

Decreased brine salinity may cause a larger length, which changes rock wettability and reduces the force of attraction at the COBR contact. The extended EDL is thought to have caused these changes in rock wettability, which resulted in the IOR observed during low salinity water flooding in carbonates. The calcite zeta potential may be affected by the adsorption of potential-determining ions (PDI) onto the calcite surface from the salt solution. The common practice of adding 𝑆𝑜4 2− to seawater causes its adsorption mostly on the surface of the calcite, changing the calcite-salt potential from positive to negative [9]. The base and acid numbers of the crude oil also influence a rock's wettability condition [12]. When the surface charges at the rock-brine and brine oil boundaries are equal, it seems that wettability alteration in carbonates is triggered, and when low salinity brine or seawater is used, the surface charge of limestone changes from positive to negative. Changes in the surface charge of the brine/rock interface were linked to the binding of certain ions to the brine/rock interface. The similar surface charges lead to an overall repulsive disjoining pressure larger than the binding force at both the rock/brine and oil/brine interfaces. This results in a thicker and more stable water layer between the oil and rock, resulting in a change from oil-wet to water-wet. Mahani et al. measured the pressure disjoining at the COBR interface of the scattered limestone rock in the brine formation (239,394 ppm). They found that the COBR interface's total interaction potential was negative at (25°, 50°, and 70°). Mahani et al. hypothesized that the deflated EDL of both the brine/oil and brine/rock interfaces had a dominating influence on the overall disjoining pressure, resulting in oil-wetness. Using low salinity brine and sea water brine, respectively, a negative surface charge and a positive whole-disjoining pressure were produced at the brine-rock interface. Due to this, the water-wetness of limestone was enhanced, and a repulsive force was created at the COBR contact [13].

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the success of low-salinity water injection strongly depends on specific reservoir conditions, including rock mineralogy, crude oil composition, salinity of the water produced and the presence of divalent ions such as calcium, magnesium and Sulfate. Experimental studies indicate that in carbonate reservoirs, wettability variations are mainly determined by mechanisms such as multivalent ion exchange and expansion of the double electrical layer. These processes weaken the adhesion forces at the oil-rock interface, promote water film stability and make the rock surface more hydrophilic. Although laboratory studies and some field applications have given encouraging results, the underlying mechanisms of low salinity water injection remain complex and are not universally applicable to all reservoirs. Variations in temperature, chemistry and mineral composition of brine can have a significant impact on performance, highlighting the importance of proper reservoir selection and brine optimization prior to field implementation. In conclusion, low salinity water injection is a promising and environmentally friendly method for improving oil recovery, with a significant potential for increased oil production when applied under optimal conditions. Further research, particularly at the oilfield level, is needed to better understand the mechanisms, improve predictability and make strong recommendations for broader application of this technology in future petroleum developments.

References:

- D. W. Green and P. G. Willhite, “Enhanced Oil Recovery (Willhite).pdf.” p. 1, 1998.

- L. Zhang et al., “Experimental Investigation of Low-Salinity Water Flooding in a Low-Permeability Oil Reservoir,” Energy and Fuels, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 3108–3118, 2018, doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b03704.

- A. Aljaberi and M. Sohrabi, “A new approach to simulate low salinity water flooding in carbonate reservoir,” SPE Middle East Oil Gas Show Conf. MEOS, Proc., vol. 2019-March, 2019, doi: 10.2118/195081-ms.

- C. Gem, “Modeling of Low Salinity Water Flooding Clastics and Carbonates”.

- A. Katende and F. Sagala, “A critical review of low salinity water flooding: Mechanism, laboratory and field application,” J. Mol. Liq., vol. 278, pp. 627– 649, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.01.037.

- J. T. Tetteh, P. V. Brady, and R. Barati Ghahfarokhi, “Review of low salinity waterflooding in carbonate rocks: mechanisms, investigation techniques, and future directions,” Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 284, p. 102253, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2020.102253.

- E. W. Al Shalabi and K. Sepehrnoori, Low Salinity and Engineered Water Injection for Sandstone and Carbonate Reservoirs. 2017.

- J. O. Adegbite, E. W. Al-Shalabi, and B. Ghosh, “Geochemical modeling of engineered water injection effect on oil recovery from carbonate cores,” J. Pet. Sci. Eng., vol. 170, no. December 2017, pp. 696–711, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2018.06.079.

- H. Mahani, A. L. Keya, S. Berg, W. B. Bartels, R. Nasralla, and W. R. Rossen, “Insights into the mechanism of wettability alteration by low-salinity flooding (LSF) in carbonates,” Energy and Fuels, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 1352– 1367, 2015, doi: 10.1021/ef5023847.

- M. A. Brown, A. Goel, and Z. Abbas, “Electrical Double Layer Effect of Electrolyte Concentration on the Stern Layer Thickness at a Charged Interface Angewandte,” pp. 3790–3794, 2016, doi: 10.1002/anie.201512025.

- A. Al-Khafaji and D. Wen, “Quantification of wettability characteristics for carbonates using different salinities,” J. Pet. Sci. Eng., vol. 173, pp. 501–511, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2018.10.044.

- J. S. Buckley, Y. Liu, and S. Monsterleet, “Mechanisms of Wetting Alteration by Crude Oils,” SPE J., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 54–61, 1998, doi: 10.2118/37230- PA.

- W. J. de Bruin, “Simulation of Geochemical Processes during Low Salinity Water Flooding by Coupling Multiphase Buckley-Leverett Flow to the Geochemical Package PHREEQC,” Delpht Msc thesis, no. August, 2012.