1. Introduction

The architectural unit common to all human cultures is the private house. From an archaeological point of view, the house is a valuable clue to the discovery of several types of information. It may be especially useful in answering such questions about its inhabitants as whether they were rich or poor and how they lived their everyday lives. This paper will consider these points in the course of an examination by feature of the domestic architecture of the second millennium B. C. as it focusses on the question as to whether it is possible or useful to formulate a standard house type for this period. In addition, this paper is a catalogue of examples of second millennium B. C. houses in Mesopotamia.

Research objectives.The research aims to show the architectural styles of houses that existed in the second millennium BC, and focus on the Typical (Model) style, which was more common and dominant in that period.

Research problem. The research problem, namely whether these houses are the result of the intellectual and cultural development of the inhabitants of that region or whether they came as a result of external influences and vice versa, in addition to the issue of the second floors, which is a matter of controversy among excavators until now, and did the Typical (Model) style dominate all styles and did it have a plan?

2. General Building Practice

It is well known that wood and stone are scarce in Mesopotamia and that mud and reeds are plentiful. Unbaked mud brick is the most common building material uncounted on Mesopotamian sites. Since mud brick disintegrates when exposed to moisture, more expensive baked brick was often used wherever there was likely to be constant exposure to dampness. For this reason, most of the houses which are to be discussed here have a baked brick or stone «damp- course», varying from two or three courses to as much as 1.5 meters above ground level. Probably no private houses were built entirely of stone or backed brick.

Bricks could be laid in a variety of patterns. For instance, in the Middle Assyrian level, the house in area had walls whose bricks were laid in two and a half rows, so that each course overlapped the previous one across both the width and length, providing a very solid bond [3]. Occasionally reed matting was laid at intervals up the wall for extra binding. Baked-brick tiles were used for paving, especially in courtyards and lavatories. Other floors were of pebbles or beaten mid. Plaster and whitewash were also available and were used to finish off walls and sometimes floors. Some wood was used for columns, beams and the upper part of staircases. Reeds were also used in the construction of rooves and perhaps for doors and windows as well [6].

It seems to have been the practice in the second millennium B. C. to bury the dead under the floors of houses. If this only occurred in isolated examples it would be reasonable to consider that the houses had been abandoned before the burials took place, but the examples are so numerous that the former possibility would bear investigation [13]. It is interesting in this connection to note that altars are found inside many of the private houses and in a few other places. Wells were used in many sites of the second millennium, especially those where there was no fresh water, only salty or undrinkable. Hence, that person resorted to digging wells to meet his daily household needs and to irrigate his small fields that surrounded his house, as in Qatna (In Syria) [21] and Ugarit (In Syria), which had these wells inside their houses.

Many of the equipment that was found, including basins, were spread in various corners of the house, as those corners determined their function. Their presence in the prayer room was for the purpose of purification before performing religious rituals, and in the front of the house for the purpose of purification or for placing water extracted from wells [17, 19].

Ovens and hearths are also among the equipment found in most homes of the second millennium BC. These features are found on wany sites. There is a functional difference between the two installations [10, 14]. A hearth is a small, often rectangular, receptacle used for heat and for cooking with cooking pots, in oven is used for baking bread. It is a large, beehive-shaped installation, which is heated to a high temperature before use. It is a fact which is seldom noted that, whereas a hearth is often found inside the main living area of a house, an oven is often set apart, sometimes outside the house proper.

3. Structural architectural elements In Syria

Foundations: Their function is to transfer all the loads applied to the building to the soil [5]. In Syria, they were made of stones or limestone, as for the countries of Mesopotamia, so the foundations were based on the oldest walls, which were built of mud [18].

Floors: People took care of them and leveled them using compacted clay, plaster, and stones [1].

Walls: Walls were constructed for several purposes: to carry the weight of the roof, prevent the entry of dirt and water, and for sound and thermal insulation [11]. and to define the external perimeter of the building and its internal divisions. The walls were built from clay heated by the heat of the sun, then used clay baked with fire [20].

Roofs: They have many forms, such as a flat wooden roof, as in Tell Ali al-Hajj, and sloping roofs [22].

Thresholds: They were used to prevent water from reaching inside the house, as in Ugarit [16].

Windows and doors: It generally assumed that there were no windows, or very few, in the ancient Mesopotamian house (The openings of early times were not intended for lighting but were mainly for ventilation [22]. This feature would protect the interior of the house from heat. Light and air could be drawn into the rooms from the courtyard. Although there are few walls on any site preserved to the height of a window, Ur has preserved a few holes pierced through the walls.

The remains of a reed door were also found [21]. It was provided with a pole which was meant to fit into a door socket on the ground, thus allowing it to pivot. These door sockets occur on almost every site, not only by front doors, but also between courtyards and the house proper. They are made of baked brick, stone or, as in the sumptuous residences of metal [12].

Stairs and stairs: They were built for the purpose of climbing to the roofs of those houses [8].

Columns: They were used for their ability to support the roofs and the upper building. They were made of stone, brick, and sometimes wood [7].

Arches: These are the arches through which the door opening was defined, and their types were numerous: in Assyria, semicircular [2] and cylindrical ones were used.

4. The Typical (Model) Houses Plan in Second Millennium

House plans multiplied in the second millennium, with the continued use of the Typical style. It seems that this continuity came in keeping with the cultural and economic development of the inhabitants of the second millennium BC. Man, over the generations, and whoever traces his civilizational path, we see him trying to develop everything that surrounds him and harness it for his service and comfort. This is why we find the homes of Syria and Iraq starting with simple homes. Meaning, it fulfilled narrow primary and basic needs of the requirements of life in prehistoric times, then it developed little by little in terms of its function and the multiplicity of its facilities to the better and better, and expanded to meet the daily needs that became increasing and introduce luxury, decorative and beautifying elements to the home.

We find that as the economic situation of the individual improves, he tries to find a suitable and appropriate place for his family to live and provide comfort. He may attempt to enlarge his home by purchasing a neighboring plot of land or purchasing certain facilities from his neighbor’s house and adding them to his residence. In this case, this may be the result of an increase in the number of family members and insufficient basic facilities in the house. basic, so the homeowner is forced to take this procedure.

Simple Style . It is the house whose facilities are less than the Typical (Model) house and the central courtyard is missing or it lacks a number of main rooms, which is what used to be a room between two and three rooms, and here we distinguish in this type two branches.

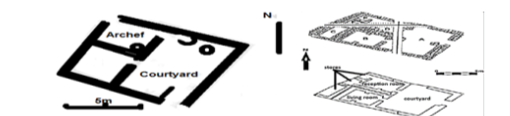

— Simple (with a front entrance), consisting of three rooms, with one room in the front, which is the largest, and two rooms behind it. It was widely spread in the Middle Bronze Age [1, 14] in Iraq. This is an old tradition that has been widespread since the ancient Bronze Age. This style has been in common use since the ancient Bronze Age in Syria and is therefore a Syrian influence. (Fig. 1, 2).

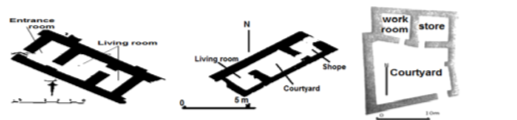

— Simple (linear), consisting of two to four rooms, but in the form of a straight line, and it was common (Fig. 3). The opinions of researchers and excavators have differed in determining the basic function of this type of house. Some of them believe that it is a residential house inhabited by families with a limited number of individuals with professions and crafts or those with limited economic income [19], and others believe that it is. This type is a place for education, reading, and writing, and on this basis, we can say that this type can provide two opportunities or purposes, such as a group of people. Where houses were found, housing waste such as a stove and a ladder were found in the middle room, clay tablets were found in the room, and also in Halawa, a stove and a stove were found in the large room [4]. The workshop was found in one of its houses, and in the second room a stove or stove was found. Enlightenment, and the area of the house may decrease and its facilities may decrease until it reaches two rooms or one room.

Fig. 1. Simple with a front entrance [15]

Fig. 2. Simple with a front entrance [16]

Fig. 3 . Simple linear [18]

5. Complex Style

These are the houses whose building facilities have increased and their size has expanded to the point that it can be more than one house. This is in terms of planning and function. They are the largest houses in size and have the most facilities. They can be more than two houses and serve more than one family. This type swells due to the addition of new sections according to the need. The resident of the house and the expansion of the family creates a spacious house with many facilities[3]. This type does not have a fixed basic plan by which it is known, and its main advantage remains the possibility of cutting off parts of it without prejudice to its ability to provide service and comfort to its residents, first and secondly, facilitating access to all its facilities and departments and to walk around inside it in a way that does not force us to resort to an external door [12].

5.1 Broken Style

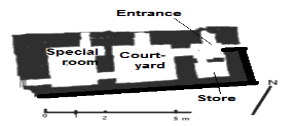

It seems that this style was related to the nature of the region, especially the mountainous and rocky ones. Houses were built and their rooms were organized in a broken line. All houses in this style were built according to one complete plan, which called the Greek plan houses. (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 . Greek plan houses [11]

5.2 Alalakh Style

It is a distinctive style characterized by regularity, as it consists of houses located on one of its long sides, a corridor in which there are several rooms located one after the other, and the row of small rooms is located perpendicular to the large rooms located on the axis of the longitudinal building. These houses are also large and have an elaborate plan [6, 12].

5.3 The Bit Hilani Style

Hilani house is a special style of architecture that was formed in the second millennium BC and we see its implementation in temples and palaces. Today, in construction research, Bit Hilani refers to a type of construction whose main characteristic is the columned entrance hall at the main entrance from the outside to the inside of the building or the courtyard entrance to the inside of the building [11]. The construction of this type of building started in the second millennium BC, these columns are often decorated in relief and have bases with animal, plant or geometric motifs or mythological creatures. After entering the hall, which usually includes a stove attached to the facing wall, the wall itself has animal motifs and mythological creatures that are worked in relief [15].

5.4 The Bazi (Bassero) Style

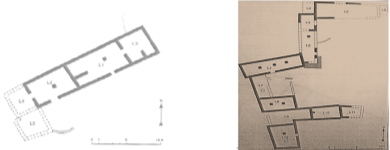

This house had a different layout than all other styles. It consisted of a longitudinally extended room (courtyard) that performed all household functions, from cooking, to work workshops, to worship. Opposite this main room was a group of square-shaped rooms, the number of which ranged from three to six rooms [9], and at the entrance there was a staircase leading to A second floor (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Bazi (Bassero) Style [17]

6. The Model (Typical) Style in Second Millennium BC

In the second millennium BC, there were many architectural styles, and this research will review the most prominent architectural styles, which are as follows:

- a small door opening inward, leading to a small vestibule off the street which contained a drain and a pot of water for washing the feet. The entrances differed in their shapes, some of which are: false entrance: where the entrance to the house after the door turns to the right or left at a right angle The use of broken and false entrances was prevalent to maintain privacy on the one hand and as a result of the climate on the other hand. If the wind enters directly, it will have a severe impact on the house.

- a courtyard, lower than the rest of the building, paved with brick, with a central drain towards which the floor sloped slightly. The courtyard is the main point in the house, as it gathers all the facilities of the house around it, and its primary function is the main outlet for sunlight and air to enter the spaces of the house. It is also the main headquarters for many daily and social activities due to the presence of kilns, ovens, hand grinders [13,20], metal casting places, and pottery making. The yard often takes the shape of a house. It may be square or rectangular.

- a guest room, usually at the back of the house, used for receiving visitors. This was a wide, shallow room, sometimes containing a brick-paved wash-room, it was placed far from the main entrance to the house due to privacy and to avoid the street. The wall that connects it to the courtyard is very thick, unlike the rest of the rooms, and it may be placed far from the living room [10].

- a kitchen, often brick-paved, with a hearth and an oven, and which was found to contain appropriate small utensils, Man practiced cooking on stoves near his homes before using the oven. The tanur occupied a room in the house due to its large size and difficulty in manufacturing, for the second millennium The kitchen now has its own room equipped with stoves, skirts and platforms. Soft to place materials on. One of the specifications of the kitchen is that it is connected to an entrance or surrounded by a courtyard for smoke and steam. Which comes out and to ensure good ventilation

- a lavatory, a small paved room with a latrine, the bathroom and the toilet were in the same room, but in the second millennium, then the bathroom was separated from the toilets, and its location changed according to the position of the stairs [11]. The toilet consisted of two tunnels next to each other, built of mud and raised above the surface of the ground. Between them was a slit containing a connected traction channel at the bottom with a sewage system. As for the bathroom, as we talked about previously, it was connected to the toilet at first, then it was separated by a small brick wall, then it was finally separated by a room separate from the toilet, which was located in the front or back of the toilet room, and was tiled and contained a drainage channel, and it might contain a stove to warm the water in days Cold winter [7].

- the stairway, a substantial brick structure passing over the top of the lavatory. The initial step was extremely high, so Wooley postulated the use of a moveable wooden step. The stairs tum at right angles on their way to the second storey. The upper part was made of wood.

- a servant's workroom, sometimes leading out into a back yard, in which querns and similar small objects were found.

- Many of the houses also had a small room behind the main house which contained an altar installation and the graves of family members, referred to as a domestic chapel. Although this fact provides interesting and useful information about private religious practice, a lengthy discussion of this phenomenon would be out of place in this paper. There were no private rooms, but there were shrines, since the homes were smaller in size than the homes of other cities. In the second millennium, this room was transformed into a suite consisting of a room for washing and wearing special clothes, a second room for practicing religious rituals, and a third room for burial

- store: When ancient man needed a place to store his few and simple needs, he had nothing better than pottery jars. When he learned agriculture, he realized the necessity of saving quantities of grains for the next season in order to plant them again. For this reason, he needed a place wider than the jars, so he placed the grains in large jars and the tools near them, for fear of them being affected by the wind and rain.

- Stables: The houses (located east Mesopotamia) in the ethno-archaeological studies already alluded to are similar in general layout to the Ur houses in the sense that they usually consist of a courtyard and several rooms, usually a family room, containing a hearth, in which the family sleeps at night, store rooms for straw and dung-cake fuel, occasionally a kitchen, and often stables for the family animals [8].

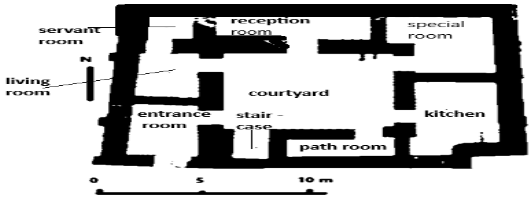

Fig. 6. Model House from Ur in Gay [8]

The Typical (Model) house prevailed in that period, which was of a square or rectangular shape. The rooms were distributed around a central courtyard, and on one side of it appeared a room containing a staircase leading to the roof or the second floor, and within that room were located the sanitary facilities. This pattern was found in most Syrian and Mesopotamia sites, which provided an idea about the residents of those houses from our knowledge of how they built their houses and what materials they used in construction, we were able to know the extent of their development and cultural and intellectual progress, and through the large size of the house we were able to determine the economic level of the residents of those houses. By studying the homes of most of the sites in the research area and during the period of the second millennium, it became clear that the Typical (Model) house dominates in most of those sites, where we were able to roughly determine the proportions.

7. Results

— Houses evolved from the simple form with an open front courtyard to the house system with a courtyard and took its fixed form of complete closure towards the outside and total openness towards the interior

— The simple house with a front has been a Syrian influence since the third millennium.

— The typical (Model) style dominated various types of homes in the second millennium.

By studying most of the homes in the research area, it was revealed that the simple style decreased in the last half of the second millennium in Syria

— The Bazi (Bassero) and Alalakh styles were specific to Syria, and it seems that Mesopotamia was influenced by these two styles.

— The complex pattern increased in Mesopotamia and Syria in the latter half of the second millennium.

— One courtyard dominated most of the homes in the studied area, with homes sometimes containing two courtyards.

— The corners of the houses were directed towards the four directions to be exposed to light and air, but in the second and last half of the second millennium, compound houses increased, as we mentioned, which took different angles and irregular sides.

— The thickness of the walls is not a measure of the presence of a second floor. When the room was large, its walls had to be thick to support the large ceiling, and the mat, which was made of mud, and some wood and reeds were unable to support a second floor.

References:

- Abd alGhane, K. (2020).The House in Syria and Iraq in the Second Millennium BC, PhD thesis, University of Damascus.

- Abo Assaf, A. (2009.) Antiquities in Mount Houran — As-Suwayda Governorate. Part 2. Damascus.

- Al-Jader, W. (1983). Preliminary results of the excavations of the University of Baghdad.

- Department of Archeology — Sippar site from (1978 to 1983). Sumer Magazine 39, Baghdad.

- Al-Dawaf, Y. (1969). Building Construction and Building Materials, Al-Shafiq Press, Baghdad.

- Akkermans, P. (2003). Archeology of Syria. From complex hunter gatherers to early urban societies.16000–300B. C. Cambridge University press.

- Alkım. U. B. (1969).The Amanus region in Turkey: New Light on the historical Geography and Archaeology. Archaeology 22.

- Al-Khader, A. (2002). History of architecture in antiquity. Damascus.

- Al Najafee, H. (1988). Revealing part of the city of Mataura in Tel Al-Seeb, Sumer Magazine, Issue 45, Baghdad.

- Al-Qaisi, K. (1989).The Iraqi House in the Old Babylonian Era in Light of the Abo Habba (Sippar) Excavations, Baghdad.

- Ismail, I. (2013). L architecture domestique sur la côte syrienne à l âge du bronze recent. universitè lumière Lyon2.vol 1.

- Kepinski, C. (1996). Spatial occupation of anew town Haradum (Iraq middle Euphrates, 17 th .18 th centuries B. C. Istanbul.

- Kramer, C. (1979). An archeological view of a contemporary Kurdish village. Domestic architecture. Household size. And Wealth.in Ethnoarcheology. Colombia University.

- Dornemann, H. (1989). one bronze age site among many in the tabqa dam salvage area. Bulletin of the American schools of oriental research. no 270. ancient Syria.

- Kramer, C. (1982). Village ethnoarchaeology. Rural Iran in archeological prespective. Newyork.

- Mallowen, M. (1935). Chagar Bazar and survey of the Khabur region. Iraq 3.

- Margeuron, J. (1979). un hilani à Emar. in archaeological reports from the Tabaq dam project Euphrates valley. Syria.

- Radon, N. (2017). Architecture and Fine Arts in the Arab World in Historical Ages until Christmas, Journal of Historical Studies, University of Damascus, No. 135.

- Stone, E. (1987). Nippur Neighborhoods, the oriental institute, university of Chicago U. S. A.

- Woolley, L. (1976).The old Babylonian period. Excavations at Ur vol VII.London.

- Yadin, Y. (1977). Executive Curator of the exhibition of excavations, Provo, Utah.

- Yassen, G. (1988). Study of the old babylionan pottery from the hamren basin Iraq with social reffernce to the Halawa, England.