Introduction

The use of students’ first language (L1) in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classrooms has been debated in language education for decades. Historically, English-only instruction was considered the most effective approach, based on the assumption that maximum exposure to the target language accelerates learning [14,1; 39,1]. In Kazakhstan, this approach discouraged the use of Kazakh or Russian during lessons, as it was believed that reliance on L1 could hinder English acquisition. However, recent research emphasizes a “multilingual turn” in language education, highlighting the importance of connecting learners’ second language (L2) to their entire linguistic repertoire [6,1; 41,1]. Studies indicate that strategic use of L1 can clarify complex grammar, explain vocabulary, and reduce cognitive load, while also supporting learner confidence and reducing anxiety [4,368; 12,713].

In Kazakhstani EFL classrooms, multilingualism is inevitable. Teachers and students frequently share Kazakh and/or Russian alongside English, making code-switching a natural occurrence. Learner proficiency also influences the necessity for L1 support: lower-proficiency students often benefit more, whereas higher-proficiency learners may prefer English-only instruction [29,1]. Despite this, many teachers remain uncertain about how to balance L1 use, and students’ perspectives are rarely included in research. Understanding both teacher practices and student perceptions is therefore essential for developing effective multilingual teaching strategies.

The main problem that this study intends to solve is a lack of clear understanding of how L1 is actually used and perceived by students. While the policy rhetoric often advocates for English-only instruction, classrooms in Kazakhstan remain multilingual, and teachers' actual practices may not necessarily align with official guidelines. There is a need to investigate both teacher practices and student perceptions with regard to the potential benefits, challenges, and practical implications of the use of L1 in the EFL classroom.

The aims of the study are as follows:

- The present study investigates how Kazakhstani secondary school EFL teachers perceive and implement L1 use in their classrooms.

- Examine how teachers’ decisions about L1 use relate to students’ English proficiency levels.

- Explore students' perceptions of L1 use, including effects on comprehension, confidence, and participation.

- Identify the perceived benefits and challenges of L1 use for teaching and learning.

- Provide insights to inform teacher training and classroom strategies for purposeful L1 integration.

These findings contribute to the growing discussion of multilingual pedagogy and translanguaging in EFL contexts. The study offers pragmatic implications for in-service teachers who work in Kazakhstan and in other multilingual classrooms with regard to balancing the use of L1 with opportunities for meaningful practice in English. Grasping teacher practice and student experiences informs language teaching that is more effective, inclusive, and sensitive to context.

Methods

This study employed a quantitative research design to investigate the use of the first language (L1), specifically Kazakh and Russian, in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classrooms in Kazakhstan. Quantitative research was considered appropriate for this study because it allows the systematic measurement of patterns, frequencies, and perceptions related to L1 use among both teachers and students [11,1; 16,1]. By using structured questionnaires, the study was able to collect standardized data, enabling the identification of trends and patterns across participants and the comparison of perspectives between teachers and students.

The study aimed to examine teacher practices regarding L1 use, as well as student perceptions, including their views on the effectiveness, benefits, and potential challenges of L1 use in English lessons. This design aligns with previous research on multilingual pedagogy, which emphasizes the importance of capturing both teacher and learner perspectives to understand the dynamics of translanguaging in the classroom [6,1; 1,1].

Participants

The study involved five secondary school EFL teachers and ten secondary school students, representing a small but purposeful sample suitable for a focused classroom-based investigation.

Three female and two male teachers participated, with teaching experience ranging from three to eighteen years. Teachers varied in terms of classroom context, teaching styles, and English proficiency levels. Their participation provided insight into how experienced educators integrate L1 into their lessons and make instructional decisions based on classroom needs.

Ten students aged 13–15 participated in the study. All students were multilingual, speaking Kazakh and/or Russian alongside English. Students were selected to reflect typical secondary school learners in Kazakhstan, representing different English proficiency levels and learning experiences.

Participation was entirely voluntary, and both teachers and students provided informed consent. Parental consent was obtained for all students, in accordance with ethical research practice. Participants were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, and they were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any point without any negative consequences. These ethical considerations were guided by the British Educational Research Association [3,1] guidelines for educational research.

Data Collection

Data for this study were collected through structured questionnaires, which were distributed to all participants in paper format during school hours. The questionnaires were designed to provide a quantitative measure of participants’ experiences and perceptions, focusing on the frequency, purpose, and perceived effectiveness of L1 use in EFL classrooms.

The questionnaires consisted of 10 statements rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

Theteacher questionnaire explored several aspects of classroom practice, including the frequency of L1 use, situations in which L1 is employed (e.g., grammar explanation, vocabulary clarification, classroom management), perceived benefits for students, challenges associated with L1 use, and how teachers adjust their practices depending on students’ English proficiency levels.

Thestudent questionnaire investigated students’ perceptions of L1 use, including its usefulness for comprehension, its impact on confidence and anxiety, its effect on participation, and students’ preferences regarding the amount of L1 used in lessons.

Participants completed the questionnaires independently to ensure unbiased responses, and the researcher clarified any potential questions before distribution. This method provided standardized and comparable data, making it suitable for quantitative analysis and for drawing meaningful conclusions about teacher and student perspectives.

Data Analysis

The responses from the questionnaires were analyzed using descriptive statistics, which allowed for a clear presentation of patterns in the data. The analysis included the following steps:

- Determining how many participants selected each Likert-scale option (1–5) for each statement.

- Calculating the proportion of participants who agreed, disagreed, or were neutral regarding each statement, to provide a clearer picture of trends across the sample.

- Computing mean scores for each statement to compare responses between teachers and students and to identify areas of consensus or divergence.

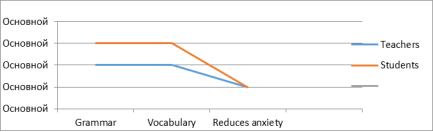

The results were presented in Chart 1, enabling a straightforward comparison of teacher and student perspectives on L1 use. This approach provides both a visual and numerical representation of key findings, which enhances the clarity and interpretability of the data.

Fig. 1. Comparison of teacher and student perspectives on L1 use

Ethical Considerations . Ethical considerations were central to the research process. Participants were fully informed about the study’s aims, procedures, and voluntary nature. They were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses. For students, parental consent was obtained in addition to student consent. All participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence. The study adhered to ethical guidelines outlined by theBritish Educational Research Association [3,1] , ensuring that the research was conducted responsibly and respectfully.

Results and Discussion

Teacher Questionnaire Results

The results of the teacher questionnaire reveal patterns in the use of L1 (Kazakh and Russian) in EFL classrooms. Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics, including average scores and agreement percentages for each statement.

Table 1

Teacher Responses to L1 Use in EFL Classrooms (N = 5)

|

Statement |

Mean |

Agree (4–5) |

Neutral (3) |

Disagree (1–2) |

|

I use L1 during English lessons |

4.2 |

80 % |

20 % |

0 % |

|

I use L1 to explain grammar |

4.0 |

80 % |

20 % |

0 % |

|

I use L1 to explain vocabulary |

4.0 |

80 % |

20 % |

0 % |

|

I use L1 for classroom management |

3.8 |

60 % |

40 % |

0 % |

|

L1 helps students feel confident |

4.0 |

80 % |

20 % |

0 % |

|

L1 reduces student anxiety |

3.8 |

60 % |

40 % |

0 % |

|

Excessive L1 may reduce English exposure |

4.2 |

80 % |

20 % |

0 % |

|

I plan when and how to use L1 |

3.6 |

60 % |

40 % |

0 % |

|

I adjust L1 use based on proficiency |

4.0 |

80 % |

20 % |

0 % |

|

L1 improves classroom participation |

3.8 |

60 % |

40 % |

0 % |

Interpretation

Teachers reported frequent use of L1, particularly for explaining grammar and vocabulary, with 80 % agreeing that it supports student understanding. L1 is also seen as a tool to reduce anxiety and increase confidence, consistent with previous findings [4,370; 9,280]. However, teachers are aware of the potential drawback that excessive L1 may limit English exposure (80 % agreement). Classroom management and planned use of L1 showed slightly lower agreement, indicating that while teachers recognize its benefits, it is not always strategically integrated.

Student Questionnaire Results

Student responses indicate that L1 is perceived as highly supportive for learning. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics from the student questionnaire.

Table 2

Student Responses to L1 Use in EFL Classrooms (N = 10)

|

Statement |

Mean |

Agree (4–5) |

Neutral (3) |

Disagree (1–2) |

|

Teacher uses L1 in lessons |

4.0 |

70 % |

20 % |

10 % |

|

L1 helps me understand grammar |

4.2 |

80 % |

10 % |

10 % |

|

L1 helps me understand vocabulary |

4.2 |

80 % |

10 % |

10 % |

|

L1 makes me feel confident |

4.0 |

70 % |

20 % |

10 % |

|

L1 reduces anxiety |

3.8 |

60 % |

30 % |

10 % |

|

L1 helps participation |

4.0 |

70 % |

20 % |

10 % |

|

L1 sometimes interrupts learning |

3.2 |

30 % |

40 % |

30 % |

|

I prefer more L1 in lessons |

3.6 |

50 % |

30 % |

20 % |

|

I prefer less L1 in lessons |

3.2 |

30 % |

40 % |

30 % |

|

L1 helps me learn English effectively |

4.0 |

70 % |

20 % |

10 % |

Interpretation

Students generally perceive L1 as beneficial for comprehension and confidence, particularly for grammar and vocabulary (80 % agreement). L1 also supports participation and reduces anxiety for many learners, aligning with previous research in multilingual EFL contexts [1,45; 18,560]. A minority of students (30 %) felt that L1 sometimes interrupts learning, and preferences for more or less L1 were mixed, reflecting the need for balanced and purposeful use.

Overall, both teachers and students recognize the positive role of L1 in supporting understanding, confidence, and classroom participation. Teachers, however, are slightly more cautious, emphasizing planning and awareness of excessive L1 use. Students are generally more open to L1, but some express concern that too much use could interfere with English immersion. These findings align with studies highlighting that strategic L1 use can enhance learning without compromising target language exposure [4,370; 9,280].

Discussion

The results suggest that purposeful L1 use is valuable in Kazakhstani EFL classrooms. Teachers’ decisions to use L1 are influenced by students’ proficiency levels, lesson content, and the goal of reducing cognitive load and anxiety. Students benefit from L1 support, particularly in understanding grammar and vocabulary, but their perceptions highlight the importance of balance.

These findings support the broader multilingual turn in language education [6,10], emphasizing that learners’ L1s are resources rather than obstacles. They also suggest practical implications: EFL teachers can integrate L1 strategically to scaffold learning while ensuring sufficient exposure to English. Training programs could include guidance on when and how to use L1 effectively to maximize comprehension and participation.

Conclusion

This study examined the use of the first language (L1), specifically Kazakh and Russian, in secondary school EFL classrooms in Kazakhstan, focusing on teacher practices and student perceptions. The findings demonstrate that L1 is employed strategically by teachers, particularly to explain grammar and vocabulary, manage classrooms, and support student confidence. Students generally perceive L1 use positively, reporting that it reduces anxiety, aids comprehension, and facilitates participation.

However, both teachers and students recognize the need for balance; excessive reliance on L1 can reduce exposure to English and limit opportunities for language practice. These results support the growing body of research advocating for multilingual pedagogies, where learners’ L1s are leveraged as resources rather than obstacles [6,3; 1,5]

The study has several implications for practice. Teacher training programs should provide guidance on strategic L1 use, emphasizing when and how it can enhance learning while maintaining sufficient English input. Additionally, classroom activities can be designed to integrate purposeful translanguaging, fostering both comprehension and participation.

In conclusion, this study highlights that purposeful and balanced L1 use can positively impact EFL learning, particularly in multilingual contexts like Kazakhstan, and that teacher awareness and planning are key to maximizing its benefits. Future research could expand to larger samples and investigate longitudinal effects of L1 use on language acquisition.

References:

- Akhmetova, I. (2021). Practitioners’ views on translanguaging in Kazakhstani EFL classrooms (Master’s thesis, Nazarbayev University). http://nur.nu.edu.kz/handle/123456789/5623

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- British Educational Research Association. (2024). Ethical guidelines for educational research (5th ed.). https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2024

- Bruen, J., & Kelly, N. (2017). Using a shared L1 to reduce cognitive overload and anxiety levels in the L2 classroom. The Language Learning Journal, 45(3), 368–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2014.908405

- Burner, T., & Carlsen, C. (2022). Teachers’ multilingual beliefs and practices in English classrooms: A scoping review. Review of Education, 11(2), 3407. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3407

- Conteh, J., & Meier, G. (2014). The multilingual turn in languages education: Opportunities and challenges. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783092246

- Cook, G. (2010). Translation in language teaching: An argument for reassessment. Oxford University Press.

- Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford University Press.

- Edstrom, A. (2006). L1 use in the L2 classroom: One teacher’s self-evaluation. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 63(2), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.63.2.275

- Galloway, N. (2020). Focus groups. Capturing the dynamics of group interaction. In H. Rose & J. McKinley (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in applied linguistics (pp. 290–301). Routledge.

- Goodman, B., & Manan, S. A. (forthcoming). Translanguaging beliefs and practices in Kazakhstan: A critical review. In K. A. da Silva & L. Makalela (Eds.), Handbook on translanguaging in the global south. Routledge.

- Goodman, B., Kambatyrova, A., Aitzhanova, K., Kerimkulova, S., & Chsherbakov, A. (2022). Institutional supports for language development through English-medium instruction: A factor analysis. TESOL Quarterly, 56(2), 713–749. https://doi.org/10.1002/TESQ.3090

- Ho, D. G. E. (2012). Focus groups. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics (pp. 1–7). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0418

- Howatt, A. P. R., & Widdowson, H. G. (2004). A history of English language teaching (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Howitt, D., & Cramer, D. (2014). Introduction to research methods in psychology (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Johnson, R. B., & Christensen L. B. (2004). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. Allyn and Bacon.

- Karabassova, L., & San Isidro, X. (2020). Towards translanguaging in CLIL: A study on teachers’ perceptions and practices in Kazakhstan. International Journal of Multilingualism, 20(2), 556–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2020.1828426

- Kaye, P. (2014, December 22). Translation activities in the language classroom. Teaching English. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/translation-activities-language-classroom

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2000). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Sage.

- Kuandykov, A. (2021). EFL teachers’ translanguaging pedagogy and the development of beliefs about translanguaging (Master’s thesis, Nazarbayev University). http://nur.nu.edu.kz/handle/123456789/5608

- Langford, B. E., Schoenfeld, G. A., & Izzo, G. (2002). Nominal grouping sessions vs focus groups. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 5(1), 58–70.

- Malmkjær, K. (2010). Language learning and translation. In Y. Gambier & L. Doorslaer (Eds.), Handbook of Translation Studies (pp. 185–190). https://doi.org/10.1075/hts.1

- May, S. (2014). The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and bilingual education. Routledge.

- Nyumba, T. O., Wilson, K., Derrick, C. J., & Mukherjee, N. (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041–210X.12860

- Richards, J. C., & Schmidt, R. W. (2010). Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Samardali, M., & Ismael, A. M. (2017). Translation as a tool for teaching English as a second language. Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics, 40, 64–69.

- Smagul, A. (2024). L1 and translation use in EFL classrooms: A quantitative survey on teachers’ attitudes in Kazakhstani secondary schools. System, 108, 103443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103443

- Tastanbek, S. (2019). Kazakhstani pre-service teacher educators’ beliefs on translanguaging (Master’s thesis, Nazarbayev University Repository). http://nur.nu.edu.kz/handle/123456789/4328

- Thornbury, S. (2006). An A-Z of ELT. Macmillan.

- Topolska-Pado, J. (2010). Use of L1 and translation in the EFL classroom. Glottodidactic Notebooks, 2, 11–25.

- Zhunussova, G. (2021). Language teachers’ attitudes towards English in a multilingual setting. System, 100, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102558