Definition:

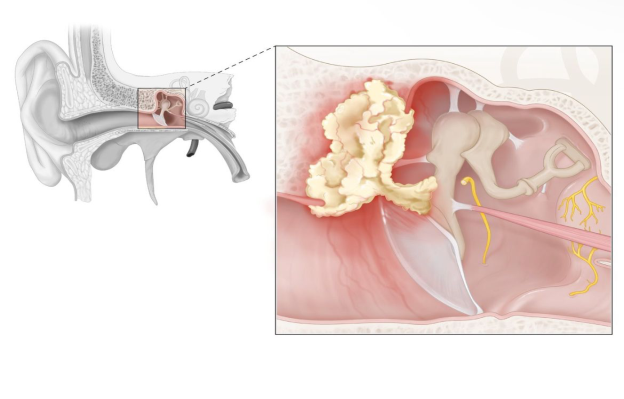

Cholesteatoma is defined as a collection of keratinized squamous epithelium trapped within the middle ear space that can erode and destroy vital locoregional structures within the temporal bone.

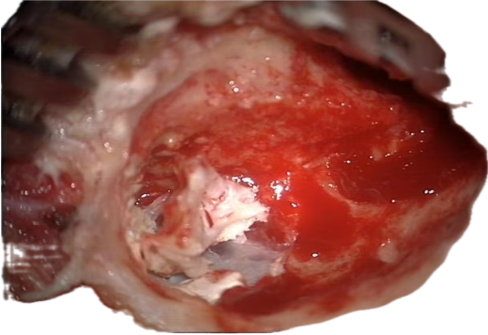

Fig. 1. Cholesteatoma

Cholesteatoma is a special form of chronic otitis media in which keratinizing squamous epithelium grows from the tympanic membrane or the auditory canal into the middle ear mucosa or mastoid. The presence of abnormal epithelium in an abnormal location triggers an inflammatory response that can destroy surrounding structures such as the ossicles. Cholesteatomas may be congenital or acquired later in life. Acquired cholesteatomas are usually associated with chronic middle ear infection. Cardinal symptoms are painless otorrhea and progressive hearing loss. Important diagnostic procedures include mastoid process x-rays, temporal bone CT scans, and audiometric tests. Left untreated, erosion of the surrounding bone by a cholesteatoma can lead to facial nerve palsy, extradural abscess, and/or sigmoid sinus thrombosis. Therefore, even if a cholesteatoma is asymptomatic, surgery is always indicated. Surgical treatment involves tympanomastoidectomy to excise the cholesteatoma, followed by repair of the damaged middle ear structures.

Etiology and pathophysiology of Cholesteatoma:

Cholesteatomas cause bony erosion by either of the following mechanisms [9]:

Consistent pressure applied over time, resulting in bony remodeling Osteoclastic activity enhanced by enzymatic processes occurring at the margin of an infected cholesteatoma

Using a scanning electron microscope, a study by Wiatr et al found that cholesteatomas with an irregular matrix structure tend to cause more destruction to the middle ear bone walls than do those with a regular, layered structure.

Keratinizing squamous epithelium grows from the tympanic membrane or the auditory canal into the middle ear mucosa or mastoid air cells.

Classification of Cholesteatoma:

- Congenital cholesteatoma:

Present at birth Embryonic nests of epidermal cells that remain in the middle ear

- Acquired cholesteatoma (more common)

Primary: eustachian tube dysfunction → tympanic membrane epithelium retracts inwards → retraction pocket

Secondary: Epithelium migrates inwards through a perforation in the tympanic membrane, which is commonly caused by recurrent/chronic otitis media.

Clinical features:

The signs and symptoms of cholesteatomas depend on the severity and location. Initially, a person may experience otorrhea (i.e., ear drainage) with or without pain and ear fullness. Congenital cholesteatomas may present in infancy with poor hearing due to obstruction of the eustachian tube (i.e., the canal that connects the middle ear to the sinuses) during development. Dizziness can occur if the semicircular canal (i.e., a structure in the internal ear responsible for balance) is compressed. Facial paralysis may also occur if there is compression of the facial nerve, which is responsible for facial movement. Infection of a cholesteatoma may result in foul-smelling discharge from the external ear.

In severe cases, a cholesteatoma may erode the middle ear bones (e.g., stapes, incus, malleus), temporal bone, or mastoid bone, affecting the central nervous system, which can cause meningitis (i.e., infection of the meninges), abscesses, fistulas (i.e., abnormal openings), and permanent hearing loss.

May be asymptomatic

– Painless otorrhea (scant but foul-smelling discharge from the affected ear)

– Conductive hearing loss

– Occurs late in primary cholesteatoma

– Occurs early in secondary cholesteatoma.

Diagnosis:

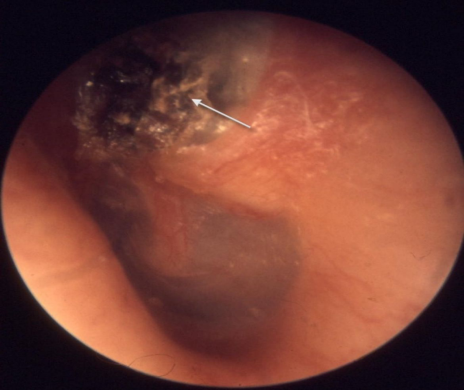

A medical expert can diagnose cholesteatomas after doing a comprehensive physical examination. It could be required to perform a thorough physical examination of the head, neck, cranial nerves, and ears. A medical practitioner may use an otoscope to check into the ear and see the cholesteatoma, a white keratinous lump. The kind and degree of any related hearing loss may also be ascertained by an audiogram, Weber, or Rinne test. While Weber and Rinne tests can determine if a person has sensorineural (i.e., inner ear damage) or conductive (i.e., outer ear damage) hearing loss, an audiogram analyzes the various frequencies and intensities that a person can hear. The afflicted ear can also be identified by these tests. If there are any neurologic symptoms, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain or use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to look into the possibilities of fistulas, brain abscesses, or bone erosion.

Otoscopic observations: Retraction pocket with squamous epithelium and debris, which frequently manifests as a brown, irregular mass, is the primary acquired condition. The white or pearly lump behind the tympanic membrane is both congenital and secondarily acquired. Imaging: to determine the extent of bone loss The mastoid process X-ray The temporal bone's CT scan Only in cases when intracranial extension is suspected is an MRI recommended. To determine the extent of hearing loss, use audiometry.

Treatment:

Therapy Surgery is usually necessary due to the possibility of complications.

- Surgicaly. It is the mainstay of treatment. Primary aim in surgical treatment is to remove the disease and render the ear safe, and second in priority is to preserve or reconstruct hearing but never at the cost of the primary aim.

Two types of surgical procedures are done to deal with cholesteatoma:

- Canal wall down procedures. They leave the mastoid cavity open into the external auditory canal so that the diseased area is fully exteriorized. The commonly performed operations for atticoantral disease are atticotomy, modified radical mastoid-ectomy and rarely, the radical mastoidectomy (see operative surgery).

- Canal wall up procedures. Here disease is removed by combined approach through the meatus and mastoid but retaining the posterior bony meatal wall intact, thereby avoiding an open mastoid cavity. It gives dry ear and permits easy reconstruction of hearing mecha-nism. However, there is danger of leaving some cho-lesteatoma behind. Incidence of residual or recurrent cholesteatoma in these cases is very high and therefore long term follow-up is essential. Some surgeon's even advise routine re-exploration in all cases after 6 months or so. Canal wall up procedures are advised only in selected cases. In combined approach or intact canal wall mastoidectomy, disease is removed both permeatally, and through cortical mastoidectomy and posterior tympanotomy approach, in which a window is created between the mastoid and middle ear, through the facial recess, to reach sinus tympani.

- Reconstructive surgery. Hearing can be restored by myringoplasty or tympanoplasty. It can be done at the time of primary surgery or as a second stage procedure.

- Conservative treatment. It has a limited role in the management of cholesteatoma but can be tried in selected cases, when cholesteatoma is small and easily accessible to suction clearance under operating microscope. Repeated suction clearance and periodic checkups are essential.

It can also be tried out in elderly patients above 65 and those who are unfit for general anaesthesia or those refusing surgery. Polyps and granulations can also be surgically removed by cup forceps or cauterized by chemical agents like silver nitrate or trichloroacetic acid. Other measures like aural toilet and dry ear precautions are also essential.

Complication:

– Destruction of ear ossicles [1]

– Perilymph fistula

– Facial nerve paralysis

– Erosion of temporal bone → extradural abscess, meningitis, sigmoid sinus thrombosis

– Aural polyp

References:

- Dhingra PL, Dhingra S. Diseases of Ear, Nose and Throat. Elsevier; 2014.

- Roland PS. Cholesteatoma. In: Meyers AD. Cholesteatoma. New York, NY: WebMD. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/860080-overview. Updated January 19, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2017.

- Lustig LR, Limb CJ, Baden R, LaSalvia MT. Chronic Otitis Media, Cholesteatoma, and Mastoiditis in Adults. In: Post TW, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/chronic-otitis-media-cholesteatoma-and-mastoiditis-in-adults. Last updated April 27, 2017. Accessed April 15, 2017.

- Liu D, Zhang H, Ma X, Dong Y. Research progress on non-coding RNAs in cholesteatoma of the middle ear. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;16(2):99–114. doi:10.21053/ceo.2022.01319

- Pachpande TG, Singh CV. Diagnosis and treatment modalities of cholesteatomas: A review. Cureus. 14(11):e31153. doi:10.7759/cureus.31153

- Richards E, Muzaffar J, Cho WS, Monksfield P, Irving R. Congenital mastoid cholesteatoma. J Int Adv Otol. 2022;18(4):308–314. doi:10.5152/iao.2022.2145