While many resource-rich countries have turned this «gift from heaven» into an advantage for economic growth and social development, many countries also suffer from what is called the «resource curse».. In particular, this curse often falls on low- and middle-income countries, with weak institutions and governance resources in addressing the challenges of converting resource wealth into service benefits. People. Some observations suggest that resources tend to be significantly correlated with human well-being in countries with relatively good institutional quality, but not significantly in countries with lower institutional quality. (Mehlum et al., 2006). The stories of three African countries — Botswana, Equatorial Guinea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) are prime examples of how resources (nature) affect growth in very different ways. economy and living standards of the people. This difference is closely related to the specific political and governance characteristics of each country.

Whether (natural) resources are a «blessing» or a «curse» for a country's development is still controversial among academic scholars as well as policy makers. Intuitionly, the abundace of resources will be an advantage, bringing a bless for the development. However, there have been many empirical studies that contradict this. In the 1990s, Sachs and Warner (1995, 1999, 2001) have shown a negative relationship between resource dependence and economic growth for the period 1970–1990, the hypothesis of «resources curse' has become increasingly popular. In addition, a number of studies have provided evidence that resource-dependent countries tend to have poorer human development, such as life expectancy, education, child mortality, etc. In addition, the abundance of natural resources can create adverse institutional and political effects. Accordingly, due to its negative effects on institutional quality, resource wealth can impede long-term growth (Rosser, 2006; Kolstad and Wiig, 2009).

Eventhough, several studies have suggested that the finding on the resource curse are not exactly clear. Some scholars argue that the «Dutch disease» tends to be overblown because it ignores the role of national policies (Davis and Tilton, 2005). Also, in some empirical studies, trade patterns are a non-significant variable in the cross-country regression on growth (Sala-i-Martin and Subramanian, 2003).

Several other studies have shown that resource impacts are heterogeneous and closely related to national institutional contexts (Costantini and Monni, 2008). From the perspective of political economy, Robinson et al. (2006) demonstrated that, in countries with good institutions, limited cronyism and corruption, natural resource returns tend to increase national income. Without these institutions, resources become a curse. Brunnschweiler and Bulte (2008) have shown that resource abundance (as measured by the amount of natural capital and mineral resource assets) is significantly associated with both growth and institutional quality. From this perspective, the resource curse seems to be a problem in measurement, while resource abundance can be an important factor in economic development.

To demonstrate that natural resources can have heterogeneous effects across countries, the article will examine the relationship between national governance, economic growth, and a number of human development indicators through case studies in three resource-rich African countries as Botswana, Equatorial Guinea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo since the early 1970s, when these countries achieved independence and built major institutions local governance, up to the years 2007–2008, before the global financial crisis. The 2008–2009 global financial crisis, which had strong negative effects on the global economy as well as on the African economy, even recalled the previous efforts for development in many countries. The negative effects of the global financial crisis can be very different from the resource impacts discussed in this study. The data used in this article are collected and calculated from the World Development Indicators dataset of the World Bank published at http://databank.worldbank.org. However, with some data not available will be collected from a number of other international organisations.

- Economic growth in three African countries

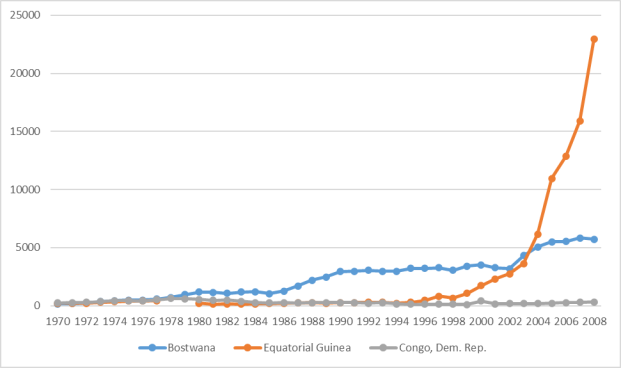

Three African countries, Botswana, Equatorial Guinea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo), after gaining independence, experienced different growth stages and patterns, depending on the policies of each country. The different growth patterns of the three countries illustrated in Figure 1 show real GDP per capita for the period 1970–2008. The difference is striking: in Botswana, during the period under consideration, the average growth rate was 6.5 % per year; Equatorial Guinea, since 1985, has grown at a rate of 9.5 %; in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, GDP per capita is falling, in real terms, at a rate of 3.5 % per year. This tells three different stories in these three resource-rich countries in Africa.

Fig. 1. GDP per capita in Botswana, DR Congo and Equatorial Guinea at current prices (USD), 1970–2008. Note: Equatorial Guine data is only available from 1980. Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators, https://databank.worldbank.org

Republic of Botswana

The Republic of Botswana is a purely continental country in Southern Africa, and has a small population, around 2.33 million in 2019. In 1966, when it gained independence from the United Kingdom, Botswana was the second poor country in the world. At that time, Botswana had only 13 km of asphalt, without any urban infrastructure and national capital. In fact, at that time Botswana had no secondary school, only 22 citizens in Botswana with university degrees. Most of the population is subsistence herders as the average income is 60 USD per year (Sebudubudu and Lotshwao, 2009). Given the backward conditions and hostile environment, at the time of independence, no one could have predicted what would change in the following decades.

Botswana's economic growth improved dramatically in 1967, when the Dee Beers Company discovered a diamond mine in Orapa. Botswana became exposed to the international diamond market in the 1970s, and Dee Beers discovered other diamond deposits in the Letlhakane and Jwaneng regions. By establishing the 'Debswana Diamond Company', the Botswana government fully benefits from the revenue from diamond mining. In fact, Botswana has become a resource rent-based economy (Dunning, 2008). Since the 1970s, the role of the mining industry in the Botswana economy has increased significantly. Currently, the mining industry contributes 40 % of GDP and 85 % of total exports, while 65 % of national exports are from diamonds. The economic growth that helped make the world's second-poorest country in 1968 was classified as a high-middle-income country for just under a decade. In 2007, GDP per capita was $12,311 in purchasing power parity (PPP), more than four times the sub-Saharan African average (World Bank 2021).

Reports of international organizations have emphasized that Botswana has enjoyed impressive economic growth due to sound macroeconomic policies, avoiding problems related to resource trade; In particular, the goal is to avoid external debt, stabilize growth, and prioritize economic diversification. These policies have been implemented within an institutional and governance system of higher standards than in other African countries and have been consistent over a long period of time (AfDB 2021, UNDP 2020).

According to Robinson (2009), the formation of state institutions in Botswana was built on the historical legacy of 'defensive modernisation', but also on the self-interest of the political elites, who desire to expand economic opportunities. This institutional system was consolidated in the post-colonial period, especially under the government of Seretse Khama. After independence, the government of Botswana formed a stable political alliance that lasted for decades and established institutions such as the Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, which laid the foundation for major budget management. Governments with specific development projects, have encouraged the adoption of fundamental, growth-promoting policies to manage diamond mining and its revenues (Sebudubudu and Lotshwao, 2009).

Equatorial Guinea

Resource revenues have had other implications for Equatorial Guinea, a tiny country of about 633,000 people located in the Gulf of Guinea. For 11 years after gaining independence from Spain (1968), the country suffered from the disastrous dictatorship of Francisco Macı` Nguema, who established an oppressive post-colonial regime. During the Macı` regime, Equatorial Guinea's small economy, based on agriculture, mainly cocoa, (accounting for more than 50 % of GDP and 97 % of exports), collapsed. GDP per capita decreased by about 40 %, most of the population lived in a state of subsistence. The government stopped providing public services such as schools or health care and the public financial system was completely disrupted (Toto Same, 2008). Thousands of people died because of the regime, while about 100,000 people, about a third of the population at the time, left the country, including European technical and managerial elites and foreign workforce, especially Nigerians, who worked in cocoa and coffee plantations. Within a few years of the dictatorship, economic mismanagement and widespread corruption devastated the economy and the infrastructure system fell into disrepair.

In 1979, Macı`s dictatorship was overthrown by a coup, ending the period of terror but continuing the police state and maintaining the previous dictatorship (Mcsherry, 2006). When Mbasogo came to power, Equatorial Guinea was the poorest country in the Central Africa and one of the most indebted in the world (HRW, 2009). Over the next decade, however, the government attempted to rebuild its political and economic institutions, developing a reconstruction program and then a medium-term adjustment program to receive foreign aid and create conditions to promote agricultural production and export.

Equatorial Guinea began to change and experienced growing in 1992 when the oil company 'Walter International' built the first background for oil exploration, followed a few years later by the 'Mobil Oil' Company. Oil production increased rapidly, rising from 6,200 bpd to about 350,000 in 2007, with output of 16 million tons and today, and now around 1.136 million bpd (OPEC 2021). In 2007, oil revenues were valued at $4.8 billion, while its production contributes almost 90 % of GDP and national exports, with the remainder coming from several other products: methanol, timber, cocoa and coffee. This heavy dependence on oil has fueled economic growth significantly: in 2007, Equatorial Guinea's GDP per capita was $30,577 (PPP), 15 times higher than the sub-Saharan African average. However, efforts to promote further growth have failed because oil revenues are channeled through oil monopoly networks and not used to improve public welfare (Mcsherry, 2006).

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Despite extreme poverty, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC, formerly Zaire) is one of the countries rich in natural resources, notably coltan, uranium, gold, zinc, copper, oil, diamonds and vast forests. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is also one of the major producers of alluvial diamonds. However, there are almost no official statistics on the DR Congo's exports of raw materials. Instead, only a handful of UN investigative reports on the illegal exploitation of the resources of the Democratic Republic of the Congo indicate that a large disparity between production and exports is attributable to the illegal exploitation of natural resources, showing illegal exploitation of the natural resources of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which produces substantial alluvial diamonds, which by some estimates account for more than 50 % of national exports (Basedau, 2005).

The country's history shows that in the context of weak institutions, resource abundance is a cause of conflict and negatively affects development. During the 1990s, Zaire was previously involved in a major conflict caused by Uganda, Rwanda and various rebel groups. In 1998, Ugandan and Rwandan leaders again occupied part of the Congo, bringing in Angola, Namibia, Chad, Rwanda, Burundi, Sudan and Zimbabwe, along with 25 armed rebel groups. A new, larger conflict, known as the «Great African War», lasted for four years (Lalji, 2007). This conflict is fueled by the fact that all parties want to control the conspicuous natural resources — copper, cobalt, diamonds, gold, uranium — of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This resource (especially diamonds) was the main source of funding for conflicts in the period 1998–2003 (Le Billon, 2008).

The 2002 Peace Agreement (the Pretoria Agreement), and the coming to power of Joseph Kabila officially ended the conflict. However, a large part of the territory of the Democratic Republic of the Congo remains outside of government control. According to the United Nations assessment, corruption, smuggling and violence have systematically exploited the resources of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, without any benefit to the people. Even so, illegal mining and trading activities in the Kivu area are completely under the control of armed groups, both insurgents and the regular army of the DRC (Global Witness, 2009). Thus, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in a time of weak institutions, abundant resources fueled conflict and corruption, and this impeded economic development, creating a kind of poverty trap that relied on resources. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in 2007, GDP per capita was $305 (PPP), only 15 % higher than in sub-Saharan Africa.

- National governance and human development issues

Comparative international indicators of governance also show sizable differences among the three countries. Despite its impressive growth rates, Equatorial Guinea ranks among the countries with the highest levels of corruption, inefficient governance and regulation, and the weakest rule of law. According to the World Bank Governance Report (2009), Equatorial Guinea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo rank relatively low in terms of corruption and governance (Table 1). According to the Index of Failing States developed by the Foundation for Peace (2009), the Democratic Republic of the Congo occupies fifth place in the international rankings and is among the countries most at risk of failure, while Guinea The Equator ranks in forty-seventh and Botswana ranks one hundred and sixteenth.

Table 1

Comparison of Country Governance Indicators (2008)

|

Voice and Accountability |

Political Stability |

Government Effectiveness |

Regulatory Quality |

Rule of Law |

Control of Corruption | |

|

Botswana |

62 |

81 |

73 |

67 |

69 |

80 |

|

DRC |

9 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

2 |

5 |

|

Equatorial Guinea |

3 |

40 |

4 |

7 |

7 |

5 |

|

The United States |

86 |

68 |

93 |

93 |

92 |

92 |

Note: Ranked by a list of 211 countries and territories compared to the United States. The higher the index, the better the governance of the country. Nguồn: World Bank (2009). Governance Matters.

The different impacts of the natural resources in the three countries are related not only to growth rates but also to people's well-being, as shown in human development indicators (Table 2). The worst can be seen in the DRC, which has one of the lowest life expectancy, child mortality and malnutrition rates, and lowest human development index in the world. In Equatorial Guinea, despite sustained growth in per capita income, key indicators of human development have not improved significantly compared with the situation in the 1990s: rising child mortality, remaining high birth rate and comparable to countries with lower GDP per capita, while the average life expectancy is 50 years.

Equatorial Guinea has the largest gap between GDP per capita and the human development index which shows that economic growth has not changed the standard of living of the people. In other words, in this country the rapid increase in oil production has resulted in a relatively high GDP per capita increase, but the poor quality of institutions has not increased the welfare of the people. In Botswana, lower mortality and malnutrition rates and higher school attendance indicate an improved standard of living. However, the spread of HIV has affected a quarter of the population, dramatically reducing health-related indicators, such as life expectancy, and is a national tragedy with enormous human and economic costs.

Table 2

Several Human Development Indicators in Botswana, Equatorial Guinea, Democratic Republic of the Congo (2007)

|

Botswana |

Guinea Xích đạo |

CHDC Congo | ||||

|

1990 |

2007 |

1990 |

2007 |

1990 |

2007 | |

|

Birth rate |

4,6 |

2, |

5,9 |

5,4 |

6,7 |

6,3 |

|

High School Completion rate |

88,9 |

88,9 |

- |

67 |

46 |

51 |

|

Life expectancy at birth |

63 |

51 |

47 |

52 |

46 |

46 |

|

Chidren Malnutrition rate |

- |

10,7 |

- |

15,7 |

- |

33,6 |

|

Mortality rate under 5 years old (per 1,000 population) |

57 |

39,7 |

170 |

206 |

200,4 |

161,4 |

|

HIV spread |

4,7 |

23,9 |

1 |

3,4 |

- |

3,2 |

|

Human Development Index (HDI) Ranking |

- |

126 |

- |

115 |

- |

177 |

Note: The extent of HIV transmission spread is determined by the proportion of the infected population in the total population aged 15–49 years.

Source: UNDP (2009) Human Development Report 2009 (New York: United Nations)

Concluding Remarks

Case studies in three African countries show that the natural resource-generated impacts can vary widely, depending on the country's context, especially the quality of governance. The case of three resource-rich African countries shows that governance is crucial for economic growth and human development. In Botswana, revenue from diamond mining has fueled sustainable growth and relative improvements in human development standards. In Equatorial Guinea, oil revenues have also fueled rapid economic growth but have had a negligible effect on the well-being of the population. In contrast, in the DRC, abundant natural resources fueled conflict and corruption, leading to negative effects on economic development.

As such, resources can be a bless for a country, but this bless can become a curse when the revenue from resources is used to finance conflicts, nurturing weak and corrupt institutions or simply wasted. Thus, the impacts that the natural resources have on human well-being do not seem to depend on the resources themselves, but on the social and institutional capacity to manage them. In this respect, the concept of resource curse has not yet highlighted the nature of the source of the negative development impact in some countries — weak resource management capacity.

References:

- African Development Bank (2021). Botswana Economic Outlook 2021. African Development Bank Group

- Auty, R.M. (ed.) (2001) Resource Abundance and Economic Development (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press).

- Basedau, M. (2005) Context matters — rethinking the resource curse in sub-Saharan Africa. Working Paper, No. 1, Global and Area Studies, German Overseas Institute.

- Brunnschweiler, C.N. and Bulte, E.H. (2008b) The resource curse revisited and revised: a tale of paradoxes and red herrings. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 55(3), pp. 248–264.

- Costantini, V. and Monni, S. (2008) Environment, human development and economic growth. Ecological Economics, 64(4), pp. 867–880.

- Davis, G.A. and Tilton, J.E. (2005) The resource curse. Natural Resources Forum, 29(3), pp. 233–242.

- Dunning, T. (2008) Crude Democracy. Natural Resource Wealth and Political Regimes (New York: Cambridge University Press).

- Global Witness (2009) Faced with a Gun, What Can You Do? War and Militarisation of Mining in Eastern Congo. A Report from Global Witness, London.

- Human Rights Watch (HRW) (2005), The curse of gold. Democratic Republic of Congo, Human Rights Watch, New York. Accessed at: http://www.hrw.org/en/node/11733/section/9

- Human Rights Watch (HRW) (2009) Well oiled: Oil and human rights in Equatorial Guinea, Human Rights Watch, New York. Accessed at: http://www.hrw.org/node/84253

- Kolstad, I. and Wiig, A. (2009) Political economy models of the resource curse: implications for policy and research. Occasional Paper, No. 40, South African Institute of International Affairs (SIIA), Johannesburg.

- Lalji, N. (2007) The resource curse revised: conflict and coltan in the Congo. Harvard International Review, 29(3), pp. 34–38.

- Le Billon, P. (2008) Diamond wars? Conflict diamonds and geographies of resource wars. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 98(2), pp. 345–372.

- Mcsherry, B. (2006) The political economy of oil in Equatorial Guinea. African Studies Quarterly, 8(3), pp. 23–45.

- Mehlum, H., Moene, K. and Torvik, R. (2006) Cursed by resources or institutions? The World Economy, 29(8), pp. 1117–1131.

- OPEC (2021). Equatorial Guinea facts and figures. https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/4319.htm

- Robinson, J.A. (2009) Botswana as a role model for country success. Research paper, No. 2009/40, United Nations University UNU-Wider.

- Robinson, J.A., Torvik, R. and Verdier, T. (2006) Political foundations of the resource curse. Journal of Development Economics, 79(2), pp. 447–468.

- Rosser, A. (2006) The political economy of the resource curse: a literature survey. Working paper, No. 268, Institute of Development Studies.

- Sachs, J.D. and Warner, A.M. (1995) Natural resource abundance and economic growth. NBER Working Paper, No. w5398, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Sachs, J.D. and Warner, A.M. (1999) The big push, natural resource booms and growth. Journal of Development Economics, 59(1), pp. 43–76.

- Sachs, J.D. and Warner, A.M. (2001) The curse of natural resources. European Economic Review, 45(4–6), pp. 827–838.

- Sala-i-Martin, X. and Subramanian, A. (2003) Addressing the natural resource curse: an illustration from Nigeria. NBER Working Paper, No. 9804, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Sebudubudu, D. and Lotshwao, K. (2009) Managing resources and the democratic order: the case of Botswana. Occasional Paper, No. 31, South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA).

- The Foundation for Peace (2009). The Fail Nations Index. Washington DC. USA

- Toto Same, A. (2008) Mineral-rich countries and Dutch disease: understanding the macroeconomic implications of windfalls and the development prospects. The case of Equatorial Guinea. Policy Research Working Paper, No. 4595, World Bank.

- UNDP (2009) UNDP, Human Development Report 2009 (New York: United Nations).

- UNDP (2020): Human Development Report 2020.

- World Bank (2009) Governance Matters 2009. Aggregate Governance Indicators 1996–2008. Washington,DC: World Bank.

- World Bank (2021). World Development Indicatiors. https://databank.worldbank.ogr