Afghanistan contains five major river basins. Meanwhile, the four-river basins are trans-boundary shared with its co-riparian countries Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. binding to equitable benefit-sharing of trans-boundary water resources management and bilateral or regional agreements and collaborative actions between the riparian countries have always been effortful for Afghanistan. Decades of unceasing war and insecurity left a fragile trans-boundary water management system in Afghanistan. Lack of security and economic stability in the country can be called the reason where the deficiencies in terms of implementation of agreements, equitable benefit-sharing and institutional framework for trans-boundary water management of its major trans-boundary river basins such as Helmand river basin alienate Afghanistan from collaborative actions with its co-riparian countries. In this paper, the initiatives and plans which have been implemented by the Afghan government for enhancing equitable benefit-sharing of water resources and developing a suitable mechanism for managing trans-boundary water between Afghanistan and its riparian country Islamic Republic of Iran have been analyzed. Furthermore, Afghanistan has been experiencing in last four decades more challenges in trans-boundary water management based on management equitably with its riparian countries. Based on academic and policy literatures being reviewed and some solutions for overcoming the challenges are provided. In conclusion, measures which are significantly needed to be taken into account further by Afghan government and international community to reach a regional cooperation for equitable benefit-sharing of trans-boundary water resources.

Keywords : Implementation of Helmand water treaty, benefit-sharing of Helmand River Basin between Afghanistan and Iran.

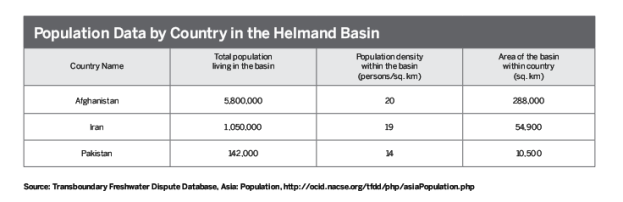

Afghanistan is rich due to its water resources and its geography provides magnificent facilities for their exploitation (King, Matthwe, Sturtewagen, Benjamin). The Helmand River Basin with an area of catchment 306,493km2(excluding non-drainage area of 40,914) is inhabited approximately 6.5 million people shared by Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan. The Helmand river basin is confined by the southern Hindu Kush ranges on the north, by the east Iranian ranges on the west and by the mountain ranges in Baluchistan province of Pakistan on the south and east (Whitney, 2006). The Helmand river is the main rivers of the basin draining water from Sia Koh mountains to the eastern mountains and the Parwan mountains and finally to the unique Sistan depression between Iran and Afghanistan (Faver and Kamal, 2004). The Sistan depression is a complex issue of wetlands lakes and lagoons; an internationally recognized haven for wetland wildlife and one of the windiest deserts in the world. More than 85 % of basin area is shared by Afghanistan where as less than 4 % by Pakistan. Since a small portion of the basin is shared by Pakistan and there are no significant tributaries flowing in and out of the Helmand River Basin to Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran are the key riparian countries which could better develop the river basin for the mutual and equitable benefit-sharing for both countries. The factors such as variability of available water resources in Helmand River Basin, inefficient management, lack of coordination among stakeholders have made water resources a scarce resource in Helmand Basin. Integrating drivers’ overall pressure on available water resource due to socioeconomic change state of water resources and response of the responsible authority to cope with issues on behalf of Helmand River Basin. Afghanistan’s trans-boundary water resources are a magnificent need for the national interest of the country afghanistan. it’s important to state that the relation of water management disputes issues on behalf of trans-boundary river basins which is quite controversial in the region. Afghanistan should find the easiest variant to pull progress to its trans-boundary water resources for national development also as peace and stability of the region. Furthermore, this development won’t be very much easy if the current amount of water use among riparian states is going to be the same when Afghanistan plans to release smaller amount of water. It is vital for Afghanistan government to develop and manage its water resources appropriately to reach its progressive goals in aspects such as, energy, agriculture, rural and urban sectors. Afghanistan water law development or simply Afghanistan’s legitimate development projects will definitely have an impact on neighboring countries who themselves are already in a state of over-exploitation of their water resources (Thomas et al. 2016). the aim of this paper is to study and analysis of Helmand water treaty and its implementation according to Afghanistan’s water law and suitable water diplomacy with its riparian country Iran for an equitable benefit-sharing of the river basin. In this paper briefly information about the Helmand tran-boundary river basin treaty and how to reach the goal equitable benefit-of sharing based on International water law within challenges are discussed. After describing all the measures and initiatives by the Afghanistan government on behalf of Helmand River Basin agreement and so far, challenges and resolution steps are explained. In conclusion, based on literatures reviewed and the research conducted by the author himself some recommendations are provided.

Fig. 1 Helmand watershed Map (Dursun Yıldız, 2015)

- Helmand Water Treaty 1973

The Helmand River Basin is a magnificent river in terms of Afghanistan’s hydro-politics. It is the longest river basin in Afghanistan which is shared between Afghanistan and Iran and the only river basin which Afghanistan has entered into a formal agreement with its riparian country Iran (Thomas & Warner 2015). The Helmand River Basin is at approximately 1,300 kilometers (800 miles). It forms the Afghan- Iranian border for fifty-five kilometers. Irrigation is ninety-five percent of all abstraction in Helmand river basin and its Sub-basins. (Yıldız, D.2017). In current situational analysis of Helmand Trans-boundary river basin in Afghanistan, equitable benefit sharing management on the basis of Helmand river basin among its co-riparian, the Islamic Republic of Iran has to be placed as a priority to gain the goal equitable sharing by strengthening water sector professionals to assess and design a suitable manner to tackle Afghanistan’s water issues. In addition, strengthening water diplomacy may led to a positive consequence of benefit-sharing. In other hand, Afghanistan has constructed two major dams on Helmand trans-boundary water river basin which are proposed to fulfill electrical needs by the names of KAJAKI and ARGHANDAB dams, both of them were constructed in 1950s. the second purpose of dams which are currently in use were to control seasonal flooding and water storage in mean time releasing it during seasonally dry times. Finally, there are six large scale irrigation projects within the basin in the center part of the river basin and one inside Iran. people’s activism in decision-making could lay the path to an equitable benefit-sharing, because the residents living aside the trans-boundary river basin are the real and first consumers of water and they can precisely state about the extra-ordinary need of them from the river basin, furthermore, it may create a win, win condition among co-riparian. The 1973 Helmand Trans-boundary Water River Basin treaty is the only official agreement that Afghanistan has. Meanwhile, the treaty addresses water allocation, a technique for equitable sharing benefit management of trans-boundary water resource of Helmand. The Helmand River Basin significantly need to be covered from all aspects in Afghanistan’s National Water Law to reduce the current disputes among riparian (Hamidreza Hajihosseini. 2016). Afghanistan is going to be strengthen due to newly established regulations by the government for tackling trans-boundary water issues which will be ready to tackle the Helmand Trans-boundary River Basin disputes with neighboring country Iran through diplomatic assessment of the dispute and negotiation by both side officials to gain a positive consequence and to facilitate opportunities for Equitable benefit sharing management. In Helmand River Treaty based on which differences between the parties must be resolved through diplomatic means, or thereafter with the great offices of third- party failing resolution, protocol two outlines an in-depth arbitration process that has fact finding and creation of an arbitration tribunal, should the parties not agree upon a suitable chair of the arbitration tribunal and in this case United Nations shall be requested to address one. Staying and sticking in compliance with treaty, Both Iran and Afghanistan have the power to watch out and find solutions for trans-boundary water resource disputes, the treaty specifies that in low flow years, the Iranian Commissioner has access to flow measurements at DEHRAWUD, and is even allowed to watch the flow and take his own measurements (protocol 1, Art,5). Afghanistan and Iranian commissioners together due to (Protocol 1, Art,6) work on measuring of water delivery. In practice, information from DEHRAWUD is formed available on an ongoing basis, not consistently, because the commission doesn’t always meet per annum. Also, delivery of water to Islamic Republic of Iran isn’t properly monitored consistent with Afghan officials and it has to be monitored. Besides, all Afghanistan government should fulfill the requirement on behalf of Helmand Trans-boundary River Basin to posses’ access to the portion of water which is said to be related to Afghanistan by implementing water governance and to submit water aspects issues to water professionals for better tackling of disputes among co-riparian (the Helmand river water treaty 1973).

2.1. Water Dispute impact on Helmand Water Treaty

The disputes on Helmand water treaty played a major role in both countries’ relationships. The foreign policy of Iran attained directly toward more water consumption and more facilities from Helmand trans-boundary river basin. back to history cooperation and trust between Iran and Afghanistan has been limited with the exception of 1973 Helmand water treaty which defined a satisfied rate of discharge from the Helmand river basin, lack of legal water sharing agreements Afghanistan developing water infrastructure is immensurable by agreements which increase Iran’s vulnerability to save and secure its interest, Iran’s adopted a paradoxical strategy. Meanwhile, pursuing its interests through legal channels, it has adopted less legitimate operations too. Iran’s policy is to achieve and reached formal agreements and to develop bilateral cooperative relationships in different aspects such as flood and drought control, political stability, regional economic development. Since 2003, Iran has entered into a UN partnership to protect the Lake Hamun and established an Iran-Afghan commission to negotiate the discharge flow of the Helmand river basin. In 2010 Afghanistan, Iran and Tajikistan reached to an agreement where to establish a tripartite “supreme water council”. Besides, that Iran follows multiple and contradictory policies in Afghanistan which is mainly influential. In other hand, Iran promised to support Afghanistan in different aspects such as economic, social and cultural and tried to develop and strengthen bilateral relationship between Tehran and Kabul, and also pressured Kabul over Afghan refugees and migrant workers living in Iran. Lent limited military support to the insurgent’s groups and attempts to create a gap between Kabul and the west and possibly tried to destabilize the government of Hamid Karzai (Katzman, 2008). Iran’s assistance to Afghanistan is undoubtedly magnificent trade agreements followed in January 2003, including efforts to replace Karachi with Iranian port of Chabahar as an Afghanistan’s trade outlet (khan, 2004). Furthermore, there is no direct evidence to prove the relationship between insurgents Taliban and Tehran. Iran’s collaborative actions toward Taliban insurgents, despite the political risks is indicative of its urgency to enter into binding water sharing agreements while the water management capacity due to destabilized situation of Afghanistan is low. Reports are that during the Taliban regime while Taliban were ruling Afghanistan Iran has dredged thirty kilometers of Helmand River Basin in order to divert the flow to storage basins where the water is pumped to other regions in Iran (Fipps, 2006). The net result is to decrease water flow to Afghan farmers in Afghanistan region and an increase in water flow taken by Iran to levels exceeding the Helmand water Treaty amount. Based on some reports inside the country some high authorities of Afghan government are also accused of protecting Iran’s interests. Over the past (Tan and Farhad, 2007). Iran’s meddlesome in Afghanistan by playing double game. Iran wants to revise the current Helmand River Basin treaty on the minimum amount of water that Afghanistan must allow to flow into Iran in a legal framework. Meanwhile, Iran has adopted competing policies on Afghanistan from one aspect contribution from other destabilizing the security to take full benefit of Helmand River Basin (NPR, 2007).

2.2. Afghanistan’s Development Project and Iran’s Objection

Iran has objected in every case to the developing projects that Afghanistan has initiated. They have always argued that dam establishment on the Helmand River Basin will reduce the flow of water reaching Iran. The provisions of the 1973 Treaty clearly with respect to the developmental projects and dams. Article V of the treaty states that Iran shall not claim for the water of Helmand River Basin more than the amount specified in Article II, even if there is an additional amount of water in the Helmand River Basin. In addition, Afghanistan shall retain all rights to use or dispose of water of Helmand River Basin as it chooses. Afghanistan contain absolute sovereignty over the remaining water of Helmand River Basin and can used it as preferred. Afghanistan has the right and power to implement agriculture, hydro-electrical and reservoir projects on the additional portion of water in Helmand River Basin. Meanwhile, Afghanistan’s responsibility is that it shall not pollute the water in River Basin and shall not take any action which will deprive Iran of its water right entirely or partially. Article V shall be read along with Article II (Iran water right), Article III (monthly distribution) and IV (climate change of the treaty (Ikramuddin Kamil, (2018).

2.3. Countermeasures

In fact, that 1973 Treaty has dispute settlement mechanism, the threat of countermeasures is atypical. Iran did not have recourse to the provisions of the 1973 Treaty which provides for the mandatory dispute’s settlement mechanism. Article IX states that where there is a dispute arisen between co-riparian states, it shall be resolved through diplomatic channels, and if it doesn’t worked, then they shall have to appeal to the third-party and finally if neither of the above efforts results in dispute resolution then the dispute shall be submitted to arbitration pursuant to the provisions of protocol no.2 annexed to the Helmand Water Treaty. In addition, to oversee the Helmand River Basin Water Treaty a joint commission from the representative of both sides has to established under Article VIII and protocol no. 1 of the treaty. Initially disputes are mostly resolved by the commissioners of both countries. Besides, that in extreme drought or force majeure shall enter into consultation and formulate and urgent dispute resolution plan according to Article IX of the Treaty and annexed protocol 2. The treaty neither explicitly nor implicitly allows for countermeasures that a party can take in case of an alleged violation of the provisions by one party. Thus, Iran’s potential countermeasures will constitute a violation of Article VIII, IX, XI, protocol 1 and protocol 2 which has detailed procedure that has to be followed for dispute settlement. Moreover, Customary International Law (Art. 22 of the Draft Article on the responsibilities of co-riparian states for internationally unjustified acts) dose allow states to take countermeasures within respect of an Internationally unjustified act that is directed against the harmed state. Although, to take into account that certain substantive and procedural conditions must met the legality of such countermeasures. A major limitation in (Article 50 of state responsibility) is that s state can’t resort to countermeasures is a situation where it is under an obligation to manage any dispute settlement procedure which is applicable between the co-riparian states. Moreover, entering into a treat a state cannot depend on the customary international law when it has contracted out of any relevant rules of the customary international law. Agreement on to be bound by treaty’s provisions co-riparian states are deviating from the general position, unless it is a Jus Cogen norm (Ikramuddin Kamil, (2018).

2.4. Continuous Violations of the 1973 Treaty

Afghanistan has continuously acted in accordance with provisions of the treaty since the treaty entered into the force in 1974. However, Afghanistan has not implemented magnificent projects on the Helmand River Basin to manage the water of Helmand River Basin properly. In other hand, has received two-three times more water than the allocated amounts under the treaty. Based on report published in 1984 indicates, inter alia, that Iran has received on an annual average basis an amount of 63 cubic meters per second or almost three times their shares under the Helmand River Basin Treaty. Comparably the Ministry of Water and Energy of Afghanistan also claims that Iran receives four times their shares under the treaty. Furthermore, the installation of approximately hundreds of water pumps by Iran that are capable of extracting thousands of cubic meters of water per year and will have adverse impact on the water in Afghanistan. Iran has built thirty dams on those rivers that flows to Afghanistan, and it has blocked the flow of water into Afghanistan. All these acts constitute a potential violation of customary international law and of Article 7 of the Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses which imposes an obligation on states not to cause significant harm to other riparian states. In conclusion, Iran’s claim on behalf of countermeasures have no legal basis under the provisions of the 1973 treaty as well as current Customary International Law. Taking countermeasures without resource to the terms of the treaty will constitute a violation of the general International law and the 1073 treaty (Ikramuddin Kamil, (2018).

2.5. Population data by country in Helmand River Basin

Population data by country in Helmand River Basin

Institutional Framework of Helmand River Basin

The Helmand Trans-boundary River Basin Institutional Structure is chronologically characterized in accordance with Afghanistan Water Law, such as the Supreme Water Council and the Ministry of Energy and Water are the main sources for Helmand trans-boundary river basin department On the other hand, newly formed Basin agencies in Afghanistan are now in charge of water allocation management in the Helmand River Basin. Furthermore, the Helmand and ARGHANDAB Water Authority (HAWA) was formed in the 1950s to manage UN-supported dams and irrigation schemes on the Helmand trans-boundary river basin. The Afghan government has recently begun work on building dams on magnificent points in accordance with a scheme devised in the 1950s for internal use, such as domestic purposes and irrigation. The majority of the dams are being built with the help of neighboring countries, such as the SALAMA DAM, which was built with India's help, and the rest are being built with the help of the Afghan government, which is issuing the budget. Since Afghanistan is an agricultural country with irrigation being the primary use of water, the construction of dams and water diversion projects would allow Afghanistan to use its share of water from the Helmand River Basin for irrigation (Aldrin A. Rivas).

- The Concept of benefit sharing

Benefits can be anything that society recognizes as valuable, such as improved livelihood, food security, gender equality, ecosystem and biodiversity improvement, aesthetics, ethics, and so on. According to Woodhouse and Philips (2009), benefit sharing is the result of a collaborative effort at various levels that, in the end, can reduce costs and increase output. The concept of benefit sharing is based on sectoral optimization, with optimization of water use in one sector leading to optimization of water use in another. When viewed from an upstream-downstream perspective, watershed management projects in upstream states, for example, can yield shared benefits through flood control, siltation reduction, and flood prevention. The implications and impacts of joint investments will be felt in the basin through technologies like irrigation and electricity, which can help ensure food security, alleviate drought, and provide renewable energy. Cooperation will support the economy, the climate, culture, and politics in any transboundary river basin. Power generation and transmission, agricultural intensification, fisheries, and industry are examples of economic benefits, while watershed management, soil protection, water regulation, flood control, and afforestation are examples of environmental benefits. Capacity building, preparation, and skill sharing are examples of social capital benefits, while political capital benefits include stability, integration, collaboration, rural water supply, and rural electrification. The list is not exhaustive, and there could be other benefits that are not observable. As a result, calculating benefit sharing becomes a challenging and dynamic process. As a result, it is up to the riparian states to determine value and distribute the basket of benefits in a fair and transparent manner.

When developing scenarios, benefit sharing should involve all types of available water. Blue water (surface plus ground), green water (water encrusted in the soil), and grey water are instances (water that can be re-usable after treatment). Similarly, a project-by-project approach is favored and suggested over a basket of benefits approach. The value of the 'basket of benefits' strategy lies in the fact that it spells out all of the potential benefits from shared wealth and investments.

Negotiating on a project-by-project basis, according to Woodhouse and Phillips (2009:9), can quickly lead to a stalemate, while the basket of benefits strategy allows opportunities to be adjusted and updated until everyone agrees on an appropriate outcome.

- Typologies of benefits

According to Sadoff and Grey (2002a), better ecosystem management can provide benefits to the river with cooperative management of shared rivers, benefits can be accrued from the river‘ (e.g. increased food production and power); with easing of tensions between riparian states, costs incurred as a result of the river can be reduced and with cooperative management of shared rivers, benefits can be accrued from the river‘ (e.g. increased food production).

Benefits to the River (Ecological River):

The Rhine River Basin Restoration and Protection Project is an example of collaborative efforts to preserve and protect shared river basins. Salmon (fish) vanished from the Rhine in the 1920s as a result of contamination. With the problem in mind, the ministers of the eight riparian states met in 1987 and devised a plan to repopulate the river with salmon under the slogan «Salmon 2000». Salmon resurfaced in the Rhine in 2000, as expected, as a result of the basin states' concerted efforts and the allocation of sufficient funds. The lessons learned from this example include how collaboration on shared water resources improves the river's ecology.

Benefits from the River (Economic River):

Two examples may be given in this context. The first is the Senegal River, where Mali, Mauritania, Guinea, and Senegal are working together to control river flows and produce hydropower using shared resources while also establishing equal profit-sharing mechanisms. To date, the Senegal River Basin Organization's (OMVS) accomplishments include: (a) the building of two dams and hydropower plants, (b) the introduction of environmental management programs, (c) the establishment of an environmental observatory, and (d) the adoption of a water charter (ENTRO, 2007).

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) is the second example, and it was planned to harness the Orange River for the benefit of both Lesotho and South Africa. LHWP served two purposes, according to Vincent Roquet & Associates Inc. (2002: 50): I to control and redirect a portion of the Orange River's water from the Lesotho mountains to the Vaal River basin through a series of dams and canals for use in the Gauteng Province of South Africa, and (ii) to take advantage of the head differential between the two rivers.

To achieve these goals, the two parties have agreed to split the building costs in roughly proportion to their expected benefits. South Africa has agreed to pay Lesotho royalties for water transferred for 50 years (it currently accounts for 5 % of Lesotho's GDP), and Lesotho will receive all hydropower produced by the project, according to the agreements reached between the two countries. Both parties have seen the water and power agreements as fair distributions of benefits (Sadoff etal, 2002a).

Benefits Because of the River (Political River):

In rivers flowing through arid and semi-arid areas, such as the Jordan, Nile, and Euphrates-Tigris, the costs incurred due to the existence of shared water supplies have remained higher. Tensions and conflicts, which in these river basins have long been the rule rather than the exception, have hindered regional integration and encouraged fragmentation. With regard to the above-mentioned rivers, Sadoff et al (2002a: 398) observe that «little flows between the basin countries except the river itself — no labor, fuel, transport, or trade.

Benefits beyond the River (Catalytic River):

It envisions more than just the river's flow, such as increased connectivity and trade. According to the Sadoff et al (2002a: 399), «cooperation on shared river management will allow and catalyze benefits «beyond the river», more directly through forward economic linkages and less directly through reduced tensions and improved relationships». The Mekong Basin is a clear example of such a profit. Laos has always provided hydropower to Thailand during the region's conflicts. Thailand has also often bought gas from Myanmar and Malaysia, as well as hydropower from Laos and China.

- Aspects of benefit sharing

According to the above-mentioned benefit typologies, the most critical aspects of benefit sharing that must be discussed are benefit sharing for whom, by whom, and because of whom. The stakeholders involved in the project must be identified. Whether it's government-to-government, people-to-people, or civil-military cooperation, profit sharing is essential. Civil society to civil society. In other word, benefit sharing should be viewed on several levels and not just at the macro stage. Wide infrastructure programs, such as the generation of electricity streams or the prevention of watershed erosion, are not the only things that need to be considered. It is essential to identify the benefits that filter down to the rural poor, whether it is through rural electrification or small-scale irrigation.

We need to ask questions like where do benefits go and whether they go to individuals or the private sector in order to track the course of benefits. This leads to the fundamental issue of benefit valuation, in which we must balance benefits such as watershed/flood protection against increases in high-value cash crops due to irrigation benefits. After that, the next step would be to monetize (value) and share the benefits by creating mechanisms. It's also important to understand the various forms of benefit sharing, such as direct vs. indirect, observable vs. immeasurable, expected vs. spillover, and domestic vs. foreign.

In line with what has been mentioned above, the basin states must consider issues such as benefit sharing arrangements in the basin, the time scale involved in reaping shared benefits, the probability of benefits being realized in terms of planning time scales (ten, fifteen, twenty years or more), and the degree to which current political economies in the basin can be used to reap shared benefits. There must be a minimum degree of benefit sharing in descending order to lead to true economic integration based on common wealth, i.e. benefits beyond the river. For example, the planned power transmission between Ethiopia and Sudan should be viewed as a means to an end rather than an end in itself. Rather, the grids should be used as integration generators, regardless of how long it takes to generate benefits for Ethiopia or convert those benefits into real growth. It is necessary to incorporate lessons learned from failed regional integrations in Africa and elsewhere, where political agreements were not translated into economic benefits. The efforts at integration failed simply because there was a significant gap between political will and economic gains, resulting in public dissatisfaction.

The term «benefit sharing» refers to more than just the allocation of benefits. It should also take into account the allocation of benefits and costs. Costs must be included in a benefit-sharing framework that has a benefit-cost-sharing system. Additional layers of sharing across industries become feasible when benefit sharing is considered at the level of entire basin. When agriculture is intensified as a result of more effective and intensive farming practices in areas with fertile soils and a favorable environment, for example, the overall regional food production and security will increase.

As a result, water that was previously used in inefficient ways for food production could be released for use in new beneficial ways including industrial growth. Benefit sharing in the form of an entire basin explores how more efficiently using and handling water in all industries can produce new additional benefits. That is, it would enable researchers to investigate how a collaborative approach to power generation or watershed management could provide a fresh perspective on water use in agriculture. The aim of the strategy is to see what new possibilities can arise as a result of taking into account the combined effects of water resource management across industries and countries. This approach is based on the idea that if water usage in one sector is optimized, it can lead to and allow water use optimization in other sectors, potentially raising the net gain to the basin as a whole. This concept is well-known at the national level and has long served as the foundation for water supply master planning around the world. However, extending this optimization and conjunctive usage thinking to the entire river basin presents a unique challenge. The study's main aim is to draw attention to the idea of Benefit- Sharing and its structure in general, as well as in the context of the Helmand River Basin HRB).

- Principles of international water law

Article 38 (1) of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) Statute of 1946 is widely regarded as a declaration of international law sources. Article 38 (1.a) allows the court to apply international conventions, whether general or specific, that the contesting states have specifically recognized. The court is required by Article 38 (1.b) to apply international customs as proof of general practice recognized as law. The court is required by Article 38 (1.c) to enforce general principles of law accepted by civilized nations. This section summarizes some of the most relevant customary and general principles of international law that apply to the management of transboundary water resources and are widely recognized around the world.

Principle of equitable and reasonable utilization

The theory of minimal territorial sovereignty includes this use-oriented concept as a subset. It ensures that each basin state receives a fair and proportional share of water resources for beneficial uses within its borders (Article IV of the Helsinki Rules 1966 and Article 5 of the UN Watercourses Convention, 1997). Equitable and fair use is based on mutual sovereignty and equality of rights, although it does not always imply an equitable share of the waters. Related variables, such as the basin's geography, hydrology, population based on the waters, economic and social needs, current water use, and potential water use, all play a role in deciding an equitable and reasonable share. State law, legal rulings, and international codifications all support this theory (Birnie and Boyle, 2002, p.302). The International Court of Justice's decision on the Gabcikovo-Naymaros Project in 1997 supported the equitable and reasonable use principle enshrined in Article 5 of the UN Watercourses Convention. The 1966 Helsinki Rules (Articles IV, V, VII, X, XXIX [4]), the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention (Articles 5, 6, 7, 15, 16, 17, 19), the 1995 SADC protocol on shared watercourse systems (Article 2), the 2002 Sava River Basin Agreement (Articles 7–9), the 1996 Mahakali River Treaty (Articles 3, 7, 8, 9), the 1995 Mekong Agreement (Articles 4–6, 26),20.

Obligation not to cause significant harm

The theory of restricted territorial jurisdiction includes this concept as well (Eckstein, 2002, p.82). According to this concept, no state in an international drainage basin can use the watercourses on its territory in a way that causes significant harm to other basin states or the environment, including harm to human health or safety, beneficial use of the waters, or the watercourse systems' living organisms. International water and environmental law have long accepted this principle (Khalid, 2004, p.11). However, the issue of what constitutes a «significant harm» and how to classify «harm» as a «significant harm» remains unanswered. It is now regarded as part of universal customary law (Eckstein, 2002, pp.82–83). This concept is enshrined in the 1966 Helsinki Rules (Articles V, X, XI, XXIX [2]), the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention (Articles 7, 10, 12, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21.2, 22, 26.2, 27, 28.1, 28.3), and the 1995 SADC Protocol on Shared Watercourse Systems (Articles 7, 10, 12, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21.2, 22, 26.2, 27, 28.1, 28.3). (Article 2), Articles 2, 9 of the 2002 Sava River Basin Agreement, Articles 7, 8, 9 of the 1996 Mahakali River Treaty, Articles 3, 7, 8 of the 1995 Mekong Agreement, Articles 8, 10.2, 16 of the 2004 Berlin Rules, and 1992 Sava River Basin Water Convention of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (Articles 2.1, 2.3, 2.4, 3). Modern international environmental conventions and declarations, such as the Stockholm Declaration of the United Nations Conference on Human Environment (Principles 21, 22), the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (Principles 2, 4, 13, 24), and the Convention on Biological Diversity (Principles 2, 4, 13, 24), recognize this concept (Article 3).

Principles of notification, consultation and negotiation

In situations where the proposed use of a share watercourse by another riparian can cause significant harm to its rights or interests, any riparian state in an international watercourse is entitled to prior notice, consultation, and negotiation. International conventions, agreements, and treaties all recognize these concepts. However, most upstream countries, understandably, are frequently opposed to this principle. Just three upstream riparian countries opposed these principles, which are contained in Articles 11 to 18, during the negotiating phase of the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention: Ethiopia (Nile basin), Rwanda (Nile basin), and Turkey (Tigris–Euphrates basin) (Birnie and Boyle, 2002, p.319). When a basin State proposes to undertake, or to permit the undertaking of, a project that may significantly affect the interests of any co-basin State, it shall give such State or States notice of the project,” according to Article 3 of the International Law Association's (ILA) Complementary rules applicable to international resources (adopted at the 62nd conference held in Seoul in 1986). The notice must include «adequate details, data, and requirements for assessing the project's effects» (Manner and Metsälampi, 1988). Most modern international water conventions, treaties, and agreements incorporate these principles, such as the 1966 Helsinki Rules (XXIX [2], XXIX [3], XXIX [4], XXX, XXXI], 1997 UN Watercourses Convention (Articles 3.5, 6.2, 11–19, 24.1, 26.2, 28, 30), 1960 Indus Waters Treaty (Articles VII [2], VIII), 1995 SADC Water Protocol (Parts Three and Four, Article 22), 1996 Mahakali River Treaty (Articles 6, 9), 1995 Mekong Agreement (Articles 5, 10, 11, 24), 2004 Berlin Rules (Chapter XI, Articles 57, 58, 59, 60), and 1992 UNECE Water Convention (Article 10). Modern international environmental conventions and declarations, such as the 1992 Rio Declaration on Climate and Development (Principles 18, 19) and the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity, recognize these principles (Article 27.1).

Principles of cooperation and information exchange

Each riparian state along an international watercourse has a duty to cooperate and share data and information about the state of the watercourse, as well as current and expected uses along the watercourse (Birnie and Boyle, 2002, p.322). These principles are recommended by the Helsinki Rules of 1966 (Articles XXIX, XXXI), and are made mandatory by Articles 8 and 9 of the UN Watercourses Convention of 1997Most current international water conventions, treaties, and agreements contain these concepts, such as the 1966 Helsinki Rules (Articles XXIX [1], XXIX [2], XXXI], and the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention (Articles 5.2, 8, 9, 11, 12, 24.1, 25.1, 27, 28.3, 30), Articles VI–VIII of the Indus Waters Treaty of 1960, Articles 2–5 of the 1995 SADC protocol on shared watercourse structures Articles 3–4, 14–21 of the 2002 Sava River Basin Agreement, Articles 6, 9, 10 of the 1996 Mahakali River Treaty, and Articles 6, 9, 10 of the 1995 Mekong Agreement (Preamble, Articles 1, 2, 6, 9, 11, 15, 18, 24, 30), 2004 Berlin Rules (Chapter XI, Articles 10, 11, 56, 64), and 1992 UNECE Water Convention (Preamble, Articles 1, 2, 6, 9, 11, 15, 18, 24, 30). (Articles 6, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16). Modern international environmental conventions and declarations, such as the 1972 Stockholm Declaration of the United Nations Conference on Human Environment (Principles 13, 22, 24), the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (Principles 7, 9, 12, 13, 17, 27), and the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity, recognize these principles (Articles 5, 17).

Peaceful settlement of disputes

In the event that states in an international watercourse cannot reach an agreement by negotiation, this principle advocates that all states in the watercourse pursue a peaceful resolution of disputes. This theory was integrated into the majority of current international water conventions, treaties, and agreements, For example, the 1966 Helsinki Rules (Articles XXVI–XXVII), the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention (Article 33), the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty (Article IX, Annexure F, G), and the 1995 SADC Protocol on Shared Watercourse Systems (Article 7), Articles 1, 22–24, Annex II of the 2002 Sava River Basin Agreement, Articles 9, 11 of the 1996 Mahakali River Treaty, Articles 18.C, 24.F, 34, 35 of the 1995 Mekong Agreement, Articles 72–73 of the 2004 Berlin Rules, and Articles 72–73 of the 1992 UNECE Water Convention (Article 22, Annex IV). Modern international environmental treaties and declarations, such as the 1992 Rio Declaration on Climate and Development (Principle 26) and the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (Article 27, Annex I), recognize this principle.

- Discussion

The Helmand River, which runs across Afghanistan and Iran, is the only river basin with which Afghanistan has reached a formal agreement. It's a fascinating case study from which to draw lessons for future collaboration on other trans-boundary water supplies in the area. With a length of around 1,300 kilometers, the Helmand River is Afghanistan's longest river (800 miles). It has five tributaries and rises in the Hindu Kush mountain range about forty kilometers west of Kabul, north of the Unai Pass. It flows for 55 kilometers through the Dashti Margo desert, forming the Afghan-Iranian boundary, before flowing into the Sistan marshes and the Lake Hamun area around Zabol.

The Helmand River Basin's water resources are largely used for irrigation, but an increase in mineral salts has reduced their utility for irrigation. The basin is being pushed even further by the implementation and expansion of numerous water infrastructure projects. The Helmand River Basin's water resources are complicated by a variety of hydroelectric projects, including the Kajaki and Kamal Khan dams on the Helmand River and the Dahla Dam on the Arghandab River. Water from the Helmand River Basin is vital for Afghan and Iranian farmers in Sistan and Baluchistan. The Afghan and Iranian governments signed an agreement on September 7, 1950, creating the Helmand River Delta Commission to develop technical methods for sharing the Helmand River's water between the two countries. The commission's mission was to provide an engineering foundation for mutual agreement on the Helmand's water apportionment. It was made up of three engineers from states with no vested interests in the area who were given nonbinding advisory powers. Iran and Afghanistan did not agree with the commission’s 1951 report. However, in 1973, Iran and Afghanistan signed a bilateral treaty on the allocation of the Helmand River’s water resources. The agreement allocates 26 cubic meters per second to Iran's downstream. The treaty was never completely enforced because of the 1973 Afghan coup, the 1978–79 Iranian revolution, the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the rise and fall of the Taliban. Following the Taliban's ouster, improved ties between Kabul and Tehran have yet to yield a solution. The absolute nature of the stipulated distribution, rather than a percentage basis, seems to be the agreement's main drawback as it currently stands. In recent years, however, positive steps have been taken to resolve unresolved disagreements. In accordance with Protocol 1 of the Helmand River Treaty, Afghanistan and Iran have formed a joint Helmand River Commissioners Delegation. The Afghan and Iranian Helmand River commissioners meet on a quarterly basis to facilitate bilateral cooperation and the establishment of Helmand River subcommittees on dredging and flood control. In addition, Iran and Afghanistan have made huge attempts to work together on the Hamun Lake's reconstruction. Since 2003, they have collaborated closely with the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the UN Development Programme (UNDP), and the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through a series of trilateral meetings between Afghanistan, Iran, and UNEP. It's part of a larger network of local, medium, and large-scale projects addressing water conservation and sustainable development in the basins of the rivers that flow into the Sistan Basin. The goals: the establishment of a structured management mechanism that ensures a consistent and adequate water flow into the basin on the other side, assist in the formulation of a Strategic Action Plan (SAP) that is collectively supported by riparian countries and secures commitment to its implementation. On the other hand, the development of specific initiatives aimed at preserving and protecting the unique wetlands eco-system and its biodiversity, as well as building capacity to respond to potential natural human-made precipitation variation. For oversight and proper management of the Sistan Basin hydrological resources and associated ecosystem, it is magnificent to establish a bilateral coordination mechanism in order to hold consultations with key stakeholders including sectoral authorities, regional and local governments, local communities, and resource consumers, which is supported by the Global Environment Facility (GEF). Furthermore, a trans-boundary diagnostic analysis (TDA) of the current hydrological and natural resources of the entire Sistan Basin catchment area in Iran is urgently needed. Developing a strategic action plan for improved Sistan basin management. Iran has an obvious interest in cooperating with Afghanistan as a downstream user of the Helmand trans-boundary river basin. (MEW water sector strategy 2008).

- Recommendation

Improvement of the hydrometeorological knowledge base in Afghanistan and the region.

Afghanistan's unwillingness to participate in regional water dialogues is due, among other things, to the country's restricted hydro-meteorological capability, a lack of adequately qualified human resources (with a strong understanding of international law and the ability to negotiate in international forums), and a thirty-year awareness gap in hydrological data due to conflict.

As a matter of fact, many Afghans are concerned that they will lose in bilateral forums, nor even regional water cooperation agreements. Good policies necessitate accurate data and a deft management of well-established national interests. The lack of accurate hydro-meteorological data for the past thirty years has undoubtedly made defining interests and formulating policies at the national level difficult, let alone policies with a regional focus. In the end, the collection and maintenance of such data must be left to Afghans, which necessitates adequate Afghan capability.

The donor community, as well as Afghanistan's neighbors, should prioritize the creation of such capacity and assistance with data collection (particularly its transboundary aspects). The establishment of a clear and shared repository of scientific hydrological data on each of Afghanistan's trans-boundary river basins could be one way to achieve this aim.

Afghanistan and its neighbors will have to work together on this, with financial assistance from the international community. Water flows would be more predictable, and accessible water supplies would be more transparent at the regional level, thanks to the repository. As a result, it would serve as a shared foundation for better-informed water-related national policy initiatives that consider the interests of neighboring countries. Mutual confidence in such a data repository would be a prerequisite for its survival as well as a consequence of it. As a result, policymakers should consider putting the archive under the control of a third party. Access to such a database must be assured, unrestricted, and permanent for all countries involved.

Afghanistan and its neighbors may want to consider establishing a regional center of excellence on hydro meteorological expertise, which would bring together academic and private sector expertise from Afghanistan, its neighbors, and the donor community on all matters relating to water expertise in a related, less formal manner. Mutually beneficial scientific and technical collaboration would help to create confidence in the region and mitigate concerns for both upstream and downstream countries. The most promising starting point for any future bilateral or regional system of cooperation is to strengthen cooperation on nonpolitical, technical aspects of water. Sharing information and developing technological capabilities will help to build regional confidence and lay the groundwork for future regional collaboration on other policy issues (King, M. and Sturtewagen, B).

Establishment of a formal confidence-building framework to share water policies between Afghanistan, its neighbors, and the donor community

For interstate faith and mutual trust, policy planning must be predictable and transparent. As a result, East West Institute suggests looking into potential frameworks that would enable Afghanistan and its neighbors to share appropriate policy plans. Such structures, if designed incrementally and pragmatically, may be the cornerstone of a confidence-building regime in which signatory states are required to notify all other signatories about water-related plans. They will do so in a format that had been decided upon and with complete clarity for all signatories. Treaties such as the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe can serve as an example of how openness and predictability of policies can help to build trust (King, M. and Sturtewagen, B).

Mobilization of support from the international community to move toward regional rather than national water strategies

Afghanistan should seize the momentum of the international community's attention for its stability and growth in order to resolve immediate concerns. As previously stated, the international community has shown unprecedented interest in Afghanistan's growth, including significant aid packages for the water sector. By completely empowering the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan to enhance coordination of international water-related aid, the international community should look beyond national realities and integrate regional water policies into political and development agendas. Without a doubt, increased regional coordination of donor activities, rather than just national coordination, will help Afghanistan and the region greatly. The international community should lend its capacity and financial leverage to generate the requisite human, financial, and technical capital for Afghanistan's water sector in a more concerted manner. Exchange of experts, training opportunities, and mutual information—such as geospatial mapping and remote sensing—with neighboring states and the international community will help fill Afghanistan's thirty-year expertise gap (King, M. and Sturtewagen, B).

Launch a multilateral dialogue process to build confidence and establish an agenda for a cross-border water management mechanism and intergovernmental river-basin-based water security watchdogs.

Afghanistan and its neighbors may want to start a multilateral dialogue to establish trust and a shared understanding of the region's most pressing water issues. This could be accomplished by improving existing regional cooperation mechanisms as well as expanding beyond them.

Afghanistan and its neighbors are currently engaged in a number of bilateral and regional cooperation processes. Established structures on Afghanistan, such as the Economic Cooperation Organization and Regional Economic Cooperation Conferences, may look to expand their reach to include regional water protection as a priority.

In particular, the water-focused Interstate Coordinating Water Commission should strive to completely include Afghanistan in its operation, as a vital source of water for many of its neighbors. Furthermore, an informal gathering of scientists from Afghanistan and its neighbors could complete a joint scientific and technical assessment of the importance of developing river-basin-based hydrological mechanisms to enhance hydrological data collection, evaluation, and assessment (King, M. and Sturtewagen, B).

- Conclusion

Benefit Sharing consider possible legal and institutional ramifications of the Benefit Sharing In general, it does not appear that implementing the Benefit Sharing would cause any problems or necessitate major changes to future plans. The benefits of transboundary river basin water sharing are primarily attributed to co-riparian states' collaborative efforts to reduce costs and improve outcomes. It may also refer to sectorial optimization, which is the efficient and effective management of shared water across all sectors. The benefits of joint investments in both upstream and downstream states can include, but are not limited to, flood control, sediment mitigation, increased water supply in the basin, hydropower development, and other ecosystem functions.

In turn, the aforementioned factors will help to ensure food security, alleviate drought, and provide renewable energy. All attempts and actions in transboundary rivers, such as the Helmand River Basin, should be oriented toward defining benefit typologies, aspects of benefit sharing, scenarios of benefit sharing, and benefit optimization. Systematic monitoring and cooperation, as well as improved ecosystem management, will provide significant benefits to the river system, potentially increasing food and power production.

Beyond the rivers, however, there is another important component: riparian state cooperation, which leads to massive integrated popular economics. Governments will want to consider developing stakeholder participation mechanisms in which the benefits and drawbacks of various forms of cooperation mechanism options are addressed, and the appropriate level of cooperative action is determined. Building trust, instilling ownership, and establishing institutional credibility and stability will require appropriate involvement of interested stakeholders in the process of developing the institutional structure and its implementation.

To ensure project protection, there should be cooperation with and among national and regional governments, military and security forces, and local communities. Stakeholder participation will also assist in identifying and quantifying the benefits of growth in the Helmand River Basin.

To assess benefit sharing arrangements for the Helmand River Basin, the governments will consider holding public meetings, seminars, trainings, and community consultations organized by provincial and district-level actors. Early on in the project planning process, several public hearings should be held. Local governments, communities, and tribal members should be active in communicating various benefits (such as electricity, water supply, irrigation, and employment), as well as incorporating local customs into profit sharing systems. Governments should inform the local public about the project's social risks and develop risk reduction strategies to ensure the project's performance.

Water users engage in the concept of benefits to be exchanged at the intra-state level, as shown by the formation of Local Coordination Committees, National User Associations, and Regional Coordination of Users within the study area jurisdiction. Furthermore, water users' traditional awareness can ease in the management and protection of transboundary waters at the inter-state level. Local communities' participation in the construction of water infrastructure at an early stage can also help to avoid international water conflicts.

Additionally, identifying trade-offs in the allocation of benefits to riparian states can help to minimize negative transboundary impacts and increase the number of benefits derived from the use of shared water resources. In the implementation of equity, an equal and reasonable allocation of costs and benefits is critical. The needs and desires of states and local populations, as well as environmental conservation, must all be taken into account. Water allocation issues should also be addressed by a cooperative agreement prior to any economic gain sharing scheme, in order to avoid negative externality for downstream riparians. The issues of water property rights and benefit sharing must remain separate until a joint basin-wide authority is established in a transboundary river basin for its overall planning and management. The results of this report, based on limited data, indicate that the benefits of transboundary river basin water sharing are primarily due to co-riparian states' joint efforts to reduce costs and improve outcomes. It may also refer to sectorial optimization, which entails efficient and productive shared water management across all sectors. At the moment, much more emphasis and attention must be placed on the sharing of transboundary benefits rather than physical water presence; while the former can result in a zero-sum result, the latter can result in a positive sum. Cooperation can result in economic, environmental, social, and political benefits.

In a transboundary river, cooperation can take several forms, from data sharing to joint management. Preliminary technical cooperation will aid in the creation of a favorable climate for future collaboration. Cooperation needs a strong national policy and regulatory structure, as well as regional programs that promote it.

References:

- King, M. and Sturtewagen, B., (2010). Making the most of Afghanistan’s River Basins: Opportunities for regional cooperation, East West Institute.

- Whitney, J.W. (2006). Geology, Water and Wind in the Lower Helmand Basin, Southern Afghanistan: US Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2006–5182. US Geological Survey, Virginia.

- Favre, R. and Kamal, G. (2004). Watershed Atlas of Afghanistan: first edition-working document for planners. Kabul, Afghanistan.

- Yıldız, D., 2017. Afghanistan’s transboundary rivers and regional security Available.

- Thomas, V., Azizi, A. M., and Behzad K., 2016. Developing transboundary water resources: what perspectives for cooperation between Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan? Available at: https://www.loc.gov/item/2017332077/.

- Hamidreza Hajihosseini & Mohammadreza Hajihosseini&Saeed Morid& Majid Delavar & Martijn J. Booij. (2016). Hydrological Assessment of the 1973 Treaty on the Transboundary Helmand River, Using the SWAT Model and a Global Climate Database.

- Thomas, V. and Warner, J., 2015. Hydro politics in the Harirud/Tejen River Basin: Afghanistan and hydro — hegemon? Water International, Vol. 40, No 4, pp. 593–613.

- The Helmand water treaty. (1973). https://afghanwaters.net/en/the-helmand-river-water-treaty-1973/

- Katzman, Kenneth. (2008). Afghanistan: Post-War Governance, Security, and U. S. Policy, Congressional Research Service. updated January 14, 2008. Retrieved from www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL30588.pdf

- Khan, Afzal. (2004, July, 9). “Trade between Afghanistan and Iran Reaches Record Levels.” Eurasia Daily Monitor.

- Fipps, Guy. (2006, August, 20). Report entitled “Advancing Water and Sanitation in Afghanistan”. Retrieved from http://gfpps.tamu. edu/Afghanistan/Advancing %20US %20Efforts %20on %20Water %20- %20Afghanistan.pdf

- Tan, Vivian and Farhad, Mohammed Nader. (2007, 2, November). “Over 350,000 Afghans Repatriate from Pakistan before winter.” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Retrieved

- NPR. (2007, August, 7). National Public Radio. Retrieved from http:// www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=12555916

- MEW water sector strategy. (2008). p.28. http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/leb166572E.pdf

- MD. Thowhidul Islam, (2011), Impact of Helmand Water Dispute on the bilateral relations between Iran and Afghanistan; an Evaluation

- Ikramuddin Kamil, (2018). Legality of Potential Iranian Countermeasures against Afghanistan over Helmand River

- TFDD. Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Asia: Population. Retrieved from http://ocid.nacse.org/tfdd/php/asiaPopulation.php

- Aldrin A. Rivas, (2008). Vulnerability Assessment of Freshwater Resources in the Helmand River Basin

- Phillips, D. J. H. and Woodhouse, M.., 2009, “Transboundary Benefit sharing Framework”: Training Manual (Version 1). Prepared for Benefit Sharing Training Workshop. Addis Ababa.

- Sadoff, C. W. and Grey, D., 2002, “Beyond the river: the benefits of cooperation on international rivers”, Water Policy, Vol. 4 No.5, pp. 389–403.Available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTABOUTUS/Resources/BeyondtheRiver.pdf.

- Phillips, D. J. H., Daoudy, M., Mc Caffrey, S., Öjendal, J. and Turton, A. R., 2006. Transboundary water cooperation as a tool for conflict prevention and broader benefit‐sharing. Stockholm: Ministry for Foreign Affairs Expert Group on Development Issues (EGDI).

- MacQuarrie, P., Viriyasakultorn, V. and Wolf, A., 2008, “Promoting cooperation in the Mekong region through water conflict management, regional collaboration, and capacity building”, GMSARN International Journal, Vol. 2, pp. 175–184.

- Tafesse, T., 2009, “Benefit-Sharing Framework in Transboundary River Basins: The Case of the Eastern Nile Subbasin”, International Water Management Institute, Conference Papers, pp. 232–245.

- ENTRO. 2007. The Management of a Transboundary River: An African Cross-Learning. Report on NBI ‘s Eastern Nile Joint Multipurpose Program (ENJMP) Knowledge Exchange study Tour to the Senegal River Basin. Addis Ababa (unpublished).

- Tesfaye Tafesse. 2001. The Nile Question: Hydro politics, Legal Wrangling, Modus

- Vivendi and Perspectives. Muenster/Hamburg: Lit Verlag. Vincent Roquet & associates Inc. 2002. Benefit Sharing from Dam Projects — Phase I Desk

- Muhammad Mizanur Rahaman, (2009). Principles of international water law: creating effective transboundary water resources management. Int. J. Sustainable Society, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2009.