Labor force is the term which is often used in the economy. This term means that is the number of people who are employed and unemployed who are looking for work. However, the term does not include the jobless who are not looking for work. Firstly, we analyze economical terms which link with the labor force. We know, stay-at-home moms, retirees and students are not considered the part of the labor force. Also, discouraged workers who would like a job but have given up looking are not in the labor force. Of course, to be considered part of the labor force, we must be available, willing to work, and have looked for a job recently. The official unemployment rate measures the jobless who are still in the labor force. In particular, the size of the labor force depends not only on the number of adults but also how likely they feel they can get a job. The labor force participation rate is the number of people who are available to work as a percentage of the total population.

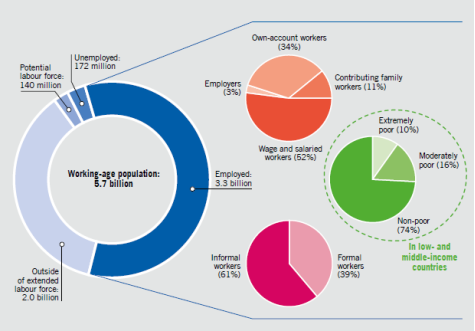

According to the latest international statistical standards, the population of working age in a country may be classified according to their labor force status in a short reference period into three mutually exclusive and exhaustive groups: person in employment, persons in unemployment and persons outside the labor force. In addition, among persons outside the labor force, it provides more detailed classification by degree of labor market attachment, enabling identification of the potential labor force.

Let’s analyze labor force in global level. Global economic growth increased by 3.6 per cent in 2017, compared with 3.2 per cent in 2016 (IMF, 2017a). This represents an upward revision of 0.2 percentage points compared to the outlook a year ago, making 2017 the first year since 2010 in which actual growth outperformed projected growth. The modest upturn in global growth was broad based, driven by expansions in developing, emerging and developed countries alike. The corresponding increase in emerging countries to 4.9 per cent in 2017 was largely driven by the end of major contractions in countries such as Brazil and the Russian Federation. Among developed countries, growth is projected to increase from 1.6 per cent in 2016 to 2.1 per cent in 2017 [1]. Looking ahead, the anticipated combination of relatively stable resource prices, a normalization of growth in most major economies and a stabilization of fixed investment at a moderate level suggests that there is unlikely to be any drag or stimulus effect sufficient to substantially alter projected global growth. Consequently, the medium-term growth projections remain at the modest level of 3.7 per cent for 2018 and beyond [2].

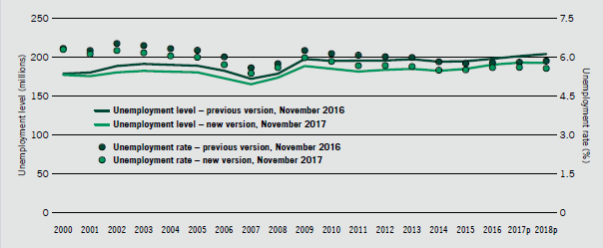

An estimated 172 million people worldwide were unemployed in 2018, which corresponds to an unemployment rate of 5.0 per cent. It is remarkable that, whereas it took only one year for the global unemployment rate to jump from 5.0 per cent in 2008 to 5.6 per cent in 2009, the recovery to the levels that prevailed before the global financial crisis has taken a full nine years. The current outlook is uncertain. Assuming stable economic conditions, the unemployment rate in many countries is projected to decline further. However, macroeconomic risks have increased and are already having a negative impact on the labour market in a number of countries. On balance, the global unemployment rate should remain at roughly the same level during 2019 and 2020. The number of people unemployed

is projected to increase by 1 million per year to reach 174 million by 2020 as a result of the expanding labour force [1].

With these improvements in employment projected to be modest, the number of workers in vulnerable forms of employment (own-account workers and contributing family workers) is likely to increase in the years to come. Globally, the significant progress achieved in the past in reducing vulnerable employment has essentially stalled since 2012. In 2017, around 42 per cent of workers (or 1.4 billion) worldwide are estimated to be in vulnerable forms of employment, while this share is expected to remain particularly high in developing and emerging countries, at above 76 per cent and 46 per cent, respectively. Worryingly, the current projection suggests that the trend is set to reverse, with the number of people in vulnerable employment projected to increase by 17 million per year in 2018 and 2019 [3].

Fig. 1. Comparison of global unemployment rates and levels, ILO Trends Econometric Models, November 2016 and November 2017

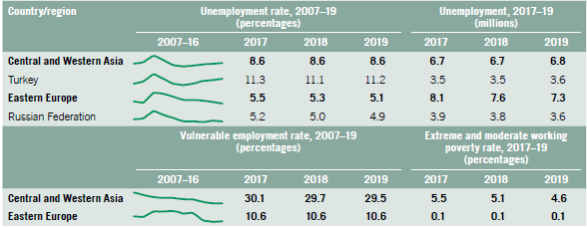

If we give attention to the rate of employment and unemployment in the Central Asia, vulnerable employment remains persistently high in Central and Western Asia, affecting more than 30 per cent of workers in 2017. This is closely associated with relatively high shares of informal employment, ranging from over 74 per cent in Tajikistan to 34.4 per cent in Turkey. As a result, the pace of reduction of the rates of extreme and moderate working poverty is decelerating. As of 2017, around 5.5 per cent of employed people were living on less than US$3.10 per day (PPP) in Central and Western Asia, a rate that is expected to decline only moderately over the next couple of years [1]. In non-EU Eastern Europe, the incidence of extreme and moderate working poverty should remain negligible. Although these countries have achieved relatively high levels of development, their share of informal employment remains high, especially if compared to the rest of Europe.

Fig. 2. The global labor market in 2018

For instance, informal employment is estimated to account for 38 per cent of total employment in Poland, and close to 36 per cent in the Russian Federation. We can see the information linked with this, in the following figure.

Fig. 3. Unemployment, employment and vulnerable employment trends and projections, Eastern Europe and Central and Western Asia, 2007–2019

In particular, in Uzbekistan unemployment rate decreased to 6,90 percent in 2018 from 7,20 percent in 2017. If we compare this rate to 2018, unemployment rate topped 9,3 percent in 2018. The highest unemployment rate was recorded in Kashkadarya, Samarkand and Fergana regions — 9,7 percent, the lowest rate in Tashkent — 7,9 percent [4].

According to the information of the National scientific center for employment under the Ministry the youth unemployment (under 30) was at 15,1 percent, those aged between 16 and 25 — over 17 percent and women 12,9 percent. The total number of manpower stands at 18.84 million. 208,9 thousand less people migrated to work abroad, with the decrease being reportedly due the expiration of their labor contracts [4].

Better calculation methods allowed to obtain more reliable employment figures in the informal sector — 7 million 870,1 thousand (59,3 percent of total number of employees). 626.48 thousand people applied to employment agencies (245,23 thousand young people aged between 16–30) in 2018 [4].

To sum up, rate of employment and unemployment effects to the economy of the states. Division of labor force throughout the world is high in USA. Also, employment rate among women becomes low compared with men. Namely, the much lower labour force participation rate of women, which stood at 48 per cent in 2018, compared with 75 per cent for men, means that around three in five of the 3.5 billion people in the global labor force in 2018 were men.

References:

- World employment social outlook. Trends 2018. International Labour Organization 2018. First published 2018

- World economic situation prospects-2018. United Nations-New York, 2018

- World employment social outlook. Trends 2019. International Labour Organization 2019. First published 2019

- www.stat.uz/annualreports